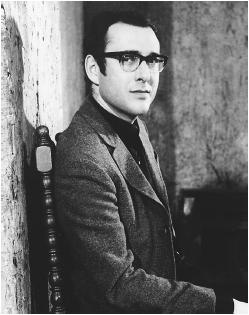

Harold Pinter - Writer

Writer.

Nationality:

British.

Born:

Hackney, London, 10 October 1930.

Education:

Attended Hackney Downs Grammar School, London; Royal Academy of Dramatic

Art, London.

Family:

Married

1) the actress Vivien Merchant, 1956 (divorced 1980), one son; 2) the

writer Lady Antonia Fraser, 1980.

Career:

1950—professional debut as actor under name David Baron;

1957—first play produced—followed by a series of plays;

1963—first film as writer,

The Servant

;

Films as Writer:

- 1963

-

The Servant (Losey) (+ ro as society man); The Caretaker ( The Guest ) (Donner)

- 1964

-

The Pumpkin Eater (Clayton)

- 1966

-

The Quiller Memorandum (Anderson)

- 1967

-

The Accident (Losey) (+ ro as Bell)

- 1968

-

The Birthday Party (Friedkin)

- 1971

-

The Go-Between (Losey)

- 1973

-

The Homecoming (Hall)

- 1976

-

The Last Tycoon (Kazan)

- 1981

-

The French Lieutenant's Woman (Reisz)

- 1983

-

Betrayal (D. Jones)

- 1985

-

Turtle Diary (Irvin) (+ ro as man in bookshop)

- 1987

-

The Room (Altman) (adapter); The Dumb Waiter (Altman); The Birthday Party (Ives—for TV) (+ ro)

- 1988

-

Mountain Language (+ d—for TV)

- 1989

-

L'ami retrouvé ( Reunion ; Der Wiedergefundene Freund ) (Schatzberg); The Heat of the Day (Morahan—for TV)

- 1990

-

The Handmaid's Tale (Schlöndorff)

- 1991

-

The Comfort of Strangers (Schrader); The Lover (Kemp-Welch)

- 1993

-

The Trial (D. Jones)

- 1999

-

Bez pogovora (Jovanovic—for TV)

- 2000

-

The Pickwick Papers

Films as Director:

- 1973

-

Butley

- 1979

-

Rear Column

- 1981

-

The Hothouse

Films as Actor:

- 1970

-

The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer (Billington) (as Steven Hench)

- 1973

-

The Tamarind Seed (Edwards)

- 1982

-

Doll's Eye (Worth)

- 1996

-

Breaking the Code (Wise—for TV) (as John Smith)

- 1997

-

Mojo (Butterworth) (as Sam Ross)

- 1998

-

Ritratto di Harold Pinter (Andò) (as himself)

- 1999

-

Mansfield Park (Rozema) (as Sir Thomas Bertram)

- 2000

-

Catastrophe (for TV)

Publications

By PINTER: plays—

The Birthday Party and Other Plays , London, 1960.

The Caretaker , London, 1960.

A Slight Ache and Other Plays , London, 1961.

The Collection , London, 1962.

The Collection , and The Lover , 1963.

The Dwarfs and Eight Revue Sketches , New York, 1965.

The Homecoming , London, 1965.

Tea Party , London, 1965.

Tea Party and Other Plays , London, 1967.

Landscape , London, 1968.

Landscape , and Silence , London, 1969.

Five Screenplays (includes The Caretaker , The Pumpkin Eater , Accident , The Servant , The Quiller Memorandum ), London, 1971; modified edition, omitting The Caretaker and including The Go-Between , London, 1971.

Old Times , London and New York, 1971.

Monologue , London, 1973.

No Man's Land , London and New York, 1975.

Plays , 4 vols., London, 1975–81; as Complete Works , New York, 4 vols., 1977–81.

The Proust Screenplay: À la Recherche du Temps Perdu , New York, 1977.

Betrayal , London, 1978.

The Hothouse , London and New York, 1980.

Family Voices , London and New York, 1981.

Other Places , London, 1983.

One for the Road , London, 1984.

Mountain Language , London, 1988.

The Heat of the Day , London, 1989.

Moonlight , New York, 1995.

Ashes to Ashes , New York, 1997.

The Proust Screenplay: A la Recherche du Temps Perdu , New York, 1999.

The Hothouse , New York, 1999.

By PINTER: other books—

Mac (nonfiction), 1968.

Poems , London, 1968.

Poems and Prose 1949–1977 , London, 1978.

I Know the Place (poetry), London, 1979.

The Screenplay of The French Lieutenant's Woman , London, 1981.

The Comfort of Strangers and Other Screenplays , London, 1990.

The Dwarfs (fiction), London, 1990.

I Know the Place , New York, 1990.

Party Time & the New World Order , New York, 1993.

One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets , New York, 1995.

99 Poems in Translation , New York, 1997.

Various Voices: Prose, Poetry, Politics, 1948–1998 , New York, 1999.

By PINTER: articles—

Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1966.

Positif (Paris), July/August 1985.

Film Comment (New York), May/June 1989.

On PINTER: books—

Hayman, Ronald, Harold Pinter , London, 1968.

Gordon, Lois, Strategems to Uncover Nakedness: The Dramas of Harold Pinter , Columbia, Missouri, 1969.

Taylor, John Russell, Harold Pinter , London, 1969.

Esslin, Martin, The Peopled Wound: The Plays of Harold Pinter , London, 1970, revised edition, London, 1977.

Hollis, James H., Harold Pinter , Carbondale, Illinois, 1970.

Sykes, Arlene, Harold Pinter , Brisbane, Queensland, 1970.

Burkman, Katherine H., The Dramatic World of Harold Pinter , Columbus, Ohio, 1971.

Ganz, Arthur, editor, Pinter: A Collection of Critical Essays , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1972.

Trussler, Simon, The Plays of Harold Pinter , London, 1973.

Quigley, Austin E., The Pinter Problem , Princeton, New Jersey, 1975.

Dukore, Bernard F., Where Laughter Stops: Pinter's Tragi-Comedy , Columbia, Missouri, 1977.

Gale, Steven H., Butter's Going Up: A Critical Analysis of Harold Pinter's Plays , Durham, North Carolina, 1977.

Bold, Alan, editor, Harold Pinter: You Never Heard Such Silence , London, 1984.

Klein, Joanne, Making Pictures: The Pinter Screenplay , Columbus, Ohio, 1985.

Cahn, Victor L., Gender and Power in the Plays of Harold Pinter , New York, 1993.

Hall, Ann. C., A Kind of Alaska: Women in the Plays of O'Neill, Pinter, and Shepard , Carbondale, Illinois, 1993.

Homan, Sidney, Pinter's Odd Man Out: Staging and Filming Old Times, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, 1993.

Knowles, Ronald, Understanding Harold Pinter , Columbia, South Carolina, 1995.

Merritt, Susan H., Pinter in Play: Critical Strategies & the Plays of Harold Pinter , Durham, 1995.

Regal, Martin S., Harold Pinter: A Question of Timing , New York, 1995.

Gussow, Mel, Conversations with Pinter , New York, 1996.

Billington, Michael, The Life & Work of Harold Pinter , New York, 1997.

Peacock, D. Keith, Harold Pinter & the New British Theatre , Westport, 1997.

Armstrong, Raymond, Kafka & Pinter: Shadow-Boxing: The Struggle Between Father & Son , New York, 1999.

On PINTER: articles—

Cinema Nuovo (Turin), May/June 1967.

Cinema Nuovo (Turin), July/August 1967.

Imagen y Sonido , September 1967.

Roud, Richard, in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1971.

Jones, Edward T., on The Go-Between in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), April 1973.

National Film Theatre Booklet (London), February 1978.

Avant-Scène (Paris), Autumn 1978.

Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 10, no. 1, 1982.

Skoop (Amsterdam), vol. 22, 4 June 1986.

Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), April and July 1988.

Chase, D., "The Pinter Principle," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1990.

Films in Review (New York), vol. 43, July/August 1992.

Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 21, no. 1, 1993.

Tucker, Stephanie, "Despair Not, Neither to Presume," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 24, no. 1, January 1996.

Hudgins, Christopher C., "Lolita 1995: the Four Filmscripts," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 25, no. 1, January 1997.

Dodson, Mary Lynn, "The French Lieutenant's Woman: Pinter and Reisz's Adaptation of John Fowles's Adaptation," in Literature/ Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 26, no. 4, October 1998.

* * *

Harold Pinter began his professional career as an actor, touring the provinces with English and Irish repertory companies before achieving success as a major playwright and screenwriter. Although he has made subsequent acting appearances, generally in small roles in his own films (among them The Servant and Accident ), and has acquired a strong reputation as a director of plays for the British stage, Pinter's fame owes much to his complex, nuance-charged writing for stage and screen.

In his early play The Birthday Party , filmed in 1968, two mysterious men terrorize a third named Stanley as he cowers in a tawdry English rooming house. The three enact a series of ritual games in an atmosphere of mounting menace, culminating in the utterly broken Stanley's removal to an unspecified destination—presumably an asylum. In post-absurdist fashion, Pinter denies his audience virtually all clarification of his characters' histories and likely futures, prompting one frustrated viewer to write: "I would be obliged if you would kindly explain to me the meaning of your play. These are the points which I do not understand: 1. Who are the two men? 2. Where did Stanley come from? 3. Were they all supposed to be normal? You will appreciate that without the answers to my questions, I cannot fully understand your play." Pinter replied: "Dear Madam: I would be obliged if you would kindly explain to me the meaning of your letter. These are the points which I do not understand: 1. Who are you? 2. Where do you come from? 3. Are you supposed to be normal? You will understand that without the answers to my questions, I cannot fully understand your letter." This interchange helps to define the characteristically elusive Pinter style and attitude. Both are based on familiarity with life's perpetual uncertainty. The little dramas we observe in life, sometimes as unwilling participants, tend to occur without benefit of sequential beginning, middle, or end. People say one thing and mean another. Strangers, casual acquaintances, close family members deny us information they prefer to withhold. Bizarre events unfold without preparation. Moods change with mercurial suddenness. To live is to be continually perplexed by others.

Pinter's dramatic methods seek to reenforce such a view of life. He rejects traditional story telling structures in favor of fractured chronology and elliptical dialogue. "The desire for verification on the part of all of us, with regard to our own experience and the experience of others, is understandable but cannot always be satisfied," he once wrote. "We are also faced with the immense difficulty, if not the impossibility of verifying the past. I don't mean merely years ago, but yesterday, this morning."

Time and memory thus serve as central Pinter subjects, functioning both technically and thematically to deny the audience the verification it instinctively desires. In Betrayal , for example, Pinter examines the romantic triangle that has developed among a married couple and the husband's best friend by reversing chronology and moving steadily backward in time, concluding the drama when the adulterous relationship first began, nine years before the start of the film. The backward telling of the tale radically alters the viewer's response and shifts attention from plot outcome to narrative point of view. The audience is mesmerized by its uncertainty, forced repeatedly to question who knew what about the relationship and when. Whose memory portrays events most accurately? The answer of course is no one's: "We all interpret a common experience quite differently," Pinter has said. "There's a common ground all right, but it's more like quicksand."

Time also figures prominently in Pinter's adaptation of three difficult novels whose narrative ambiguity he reinterprets in filmic terms. In The Go-Between (from L. P. Hartley's novel), the past is remembered as "a foreign country; they do things differently there." Here, the shifting narrative between past and present enables Pinter to emphasize the effects of cruelty so endemic to the British class system, a subject also explored in his adaptation of John Fowles's The French Lieutenant's Woman , a novel whose dazzling narrative pyrotechnics would appear to have rendered it undramatizable. Pinter's controversial solution rests on an alternation between Fowles's Victorian England and the enactment of that world in a film being shot in contemporary London. Actors acting in a film within the film thus become an appropriate Pinter metaphor for the invisible line between illusion and reality, with one story implicitly commenting on the other.

Pinter's characters say less than they mean as a thin veneer of civilized restraint keeps threatening to erupt into violence. In Accident , Homecoming , Betrayal , and other screenplays, sexual power struggles are obliquely fought in language that mocks the comedy of manners. His dialogue reads as if it were meant to be spewed, not spoken, to be articulated in tones of innuendo and menace that suggest meaning underived from the words alone. In that respect, Pinter's experience as actor and director has made a substantial if unrecognized contribution to the dynamics of his language.

Pinter also wrote the screen adaptations of novels for several films which were released in the early 1990s, including Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale , a feminist, Orwellian classic about a woman's ordeal under the authoritarian rule of the extreme right. He also wrote the screenplay for Ian McEwan's The Comfort of Strangers , the story of a young couple whose vacation in Venice evolves into a nightmare of sadomasochistic torture and murder.

Undoubtedly Pinter's greatest screenwriting challenge of the early 1990s was the offer to write the screenplay of Franz Kafka's The Trial . Pinter stated in 1992, that when he was first asked to adapt The Trial , "I immediately said yes, since I have, more or less, been waiting for this opportunity for 45 years." That Pinter was greatly inspired by Kafka would seem self-evident to anyone who had studied Pinter's early works. The Birthday Party in particular, has often been directly compared to The Trial by Pinter's critics. The Trial is, of course, the story of Joseph K., the senior bank clerk who awakens on his 30th birthday to find himself arrested by an unknown court, for an unknown crime, from which he can never be exonerated.

The Trial was released in 1993 by Angelika Films. It was filmed in Prague and was directed by David Jones who also directed the film version of Pinter's play Betrayal . Overall, Pinter's adaptation is quite faithful to the novel. The novel's famous chapter "The Cathedral" is noticeably abridged, but this is obviously necessary due to the time constraints of the filmic form.

The colorful and beautiful backdrop created for Joseph K.'s nightmarish world is a sharp contrast to Orson Welles's 1962, futuristic black-and-white adaptation of The Trial . Pinter explained in an interview that the film was intended to be "very plain without grotesqueries," unlike Welles's version which he described as being a "phantasmagoria."

The use of surreal special effects and lighting in The Trial would certainly have only detracted from this ultimate marriage of Kafka and Pinter. For Pinter is a dramatist and screenwriter whose gift it has been to make nightmarish worlds unfold by disrupting the ordinary, through the powers of language and silence.

—Mark W. Estrin, updated by Áine Doyle