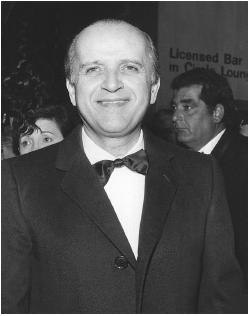

Nino Rota - Writer

Composer.

Nationality:

Italian.

Born:

Nini Rinaldi in Milan, 31 December 1911.

Education:

Attended St. Cecilia Academy, Rome, diploma, 1930; Curtis Institute,

Philadelphia; also studied with Giacome Orefice and others.

Career:

Child prodigy: composer of oratorios, operas, incidental music for stage

plays; 1933—first film score, for

Treno popolare

; 1937–38—taught at Liceo Musicale, Taranto;

1939—taught at Bari Conservatory, and director, 1950–78.

Awards:

British Academy Award for

The Godfather

, 1972; Academy Award for

The Godfather, Part II

, 1974.

Died:

In Rome, 10 April 1979.

Films as Composer:

- 1933

-

Treno popolare (Matarazzo)

- 1943

-

Zazà (Castellani); Il birichino di papa (Matarazzo)

- 1945

-

La freccia nel fianco (Lattuada); Un Americano in vacanza ( A Yank in Rome ) (Zampa)

- 1946

-

Le miserie del Signor Travet (Soldati); Roma città libera (Pagliero); Vivere in pace ( To Live in Peace ) (Zampa); Mio figlio professore (Castellani)

- 1947

-

Daniele Cortis (Soldati); Come persi la guerra (Borghesio); Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo ( Flesh Will Surrender ) (Lattuada); Albergo Luna, Camera 34 (Bragaglia)

- 1948

-

Amanti senza amore (Franciolini); Arrivederci Papà (Mastrocinque); I pirati di Capri (Ulmer and Scotese);

Senza pietà ( Without Pity ) (Lattuada); Fuga in Francia (Soldati); In nome della legge (Germi); Molti sogni per le strade (Camerini); The Glass Mountain (Cass); Proibito rubare ( Guaglio ) (Comencini); E primavera (Castellani) Nino Rota

Nino Rota - 1949

-

Obsession ( The Hidden Room ) (Dmytryk); Campane a martello ( Children of Change ) (Zampa)

- 1950

-

Napoli milionaria (de Filippo); Vita da cani (Steno and Monicelli); Donne e briganti (Soldati); E più facile che un camello ( His Last Twelve Hours ) (Zampa)

- 1951

-

Due mogli somo troppe (Camerini); Anna (Lattuada); Filum ena Marturano (de Filippo); Due soldi di speranza (Castellani); Era lui . . . síà! síà! (Metz, Marchesi, and Girolami); Peppino e Violetta (Cloche); Valley of Eagles (Young)

- 1952

-

Marito e moglie (de Filippo); The Venetian Bird ( The Assassin ) (Thomas); Something Money Can't Buy (Jackson); Le sceicco bianco ( The White Sheik ) (Fellini); Le meravigliose avventure di Guerrin Meschino (Francisci); La Regina di Saba (Francisci); I sette dell'orsa maggiore (Coletti); Totò e i re di Roma (Steno and Monicelli)

- 1953

-

L'Ennemi public no. 1 ( The Most Wanted Man ) (Verneuil) (co); Gli uomini che mascalzoni (Pellegrini); I vitelloni (Fellini); Anni facili ( Easy Years ) (Zampa); Fanciulle di lusso (Vorhaus); Noi due sole (Metz, Marchesi, and Girolami); Scampolo '53 (Bianchi); Star of India (Lubin); La mano della straniero ( The Stranger's Hand ) (Soldati)

- 1954

-

La strada (Fellini); Proibito (Monicelli); Mambo (Rossen); Musodoro (Bennati); Senso (Visconti); La grande speranza (Coletti); La domenica della buona gente (Majano); Via Padova 46 (Bianchi); Le due orfanelle (Gentilomo)

- 1955

-

Il bidone (Fellini); Un eroe dei nostri tempi (Monicelli); Amici per la pelle ( Friends for Life ) (Rossi); La bella di Roma (Comencini)

- 1956

-

War and Peace (K. Vidor); Le notti di Cabiria ( Cabiria . Nights of Cabiria ) (Fellini)

- 1957

-

Le notte bianche ( White Nights ) (Visconti); Fortunella (de Filippo); Londra chiama Polo Nord (Coletti); El medico e lo stregone (Monicelli); Il momento più bello (Emmer); Italia piccola (Soldati)

- 1958

-

Barrage contre le Pacifique ( This Angry Age ; The Sea Wall ) (Clément); Città di notte (Trieste); Un ettaro di cielo (Casadio); La Loi . . . c'est la loi ( The Law Is the Law ) (Christian-Jaque); Giovani mariti (Bolognini); Gli Italiani sono matti (Coletti)

- 1959

-

La grande guerra ( The Great War ) (Monicelli); Sons and Lovers (Cardiff); Never Take No for an Answer (Cloche and Smart)

- 1960

-

La dolce vita (Fellini); Plein soleil ( Purple Noon ) (Clément); Sotto dieci bandiere ( Under Ten Flags ) (Coletti and Narizzano); Rocco e i suoi fratelli ( Rocco and His Brothers ) (Visconti)

- 1961

-

The Best of Enemies (Hamilton); Il brigante (Castellani); Fantasmi a Roma (Pietrangeli)

- 1962

-

Boccaccio '70 (Fellini and Visconti episodes); L'isola di Arturo ( Arturo's Island ) (Damiani); I sequestrati di Altona ( The Condemned of Altona ) (De Sica); Il mafioso ( Mafioso ) (Lattuada) (co); The Reluctant Saint (Dmytryk)

- 1963

-

Mare matto (Castellani); Otto e mezzo ( 81/2 ) (Fellini); Il gattopardo ( The Leopard ) (Visconti); Il maestro di Vigevano (Petri)

- 1965

-

Giulietta degli spiriti ( Juliet of the Spirits ) (Fellini)

- 1966

-

Spara forte, piu forte, non capisco ( Shout Loud, Louder . . . I Don't Understand ) (de Filippo)

- 1967

-

The Taming of the Shrew (Zeffirelli)

- 1968

-

"Tre passi nel delirio" ep. of Histoires extraordinaires ( Spirits of the Dead ) (Fellini); Romeo and Juliet (Zeffirelli)

- 1969

-

Satyricon (Fellini)

- 1970

-

I clowns ( The Clowns ) (Fellini); Waterloo (Bondarchuk)

- 1972

-

The Godfather (Coppola); Roma (Fellini)

- 1973

-

Film d'amore e d'anarchia ( Love and Anarchy ) (Wertmüller); Amarcord (Fellini); Sunset, Sunrise (Kurohara)

- 1974

-

The Abdication (Harvey); The Godfather, Part II (Coppola)

- 1976

-

Caro Michele (Monicelli); Casanova (Fellini); Ragazzo di borgata ( Slum Boy ) (Paradisi) (co)

- 1978

-

Death on the Nile (Guillermin)

- 1979

-

Prova d'orchestra ( Orchestra Rehearsal ) (Fellini); Hurricane (Troell)

- 1986

-

I Soliti ignoti . . . vent'anni dopo

- 1987

-

Federico Fellini's Intervista (Fellini)

- 1990

-

The Godfather, Part III (Coppola)

Publications

By ROTA: article—

Nuova Rivista Musicale Italiana (Rome), vol. 5, no. 1, 1971.

On ROTA: books—

De Santi, Pier Marco, La musica di Nino Rota , Bari, 1983.

Comuzio, Ermanno, and Paolo Vecchi, 1381/2: i film di Nino Rota , Rome, 1986.

Latorre, José Maria, Nino Rota: La Imagen de la música , Barcelona, 1989.

On ROTA: articles—

Films in Review (New York), June-July 1971.

Dirigido por . . . (Barcelona), December 1973.

Film Quarterly (Berkeley, California), Winter 1974–75.

Ecran (Paris), September 1975.

Soundtrack! (Hollywood), March 1978.

Take One (Montreal), May 1979.

Bianco e Nero (Rome), July-August 1979.

Image et Son (Paris), September 1979.

Cinema Nuovo (Turin), December 1981.

Score (Lelystad, Netherlands), January 1983.

Soundtrack! (Hollywood), March and June 1987.

Mannino, F., "Nino Rota neorealista," in Revisto del Cinematografo , no. 63, April 1993.

Vallerand, F., "Musique 'classique'," in Sequences , no. 165, July/August 1993.

Dossier, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1993.

Deutsch, D.C., "Film Music," in Soundtrack ! (Hollywood), December 1996.

Simon, John, " Nights of Cabiria ," in National Review , 17 August 1998.

* * *

Nino Rota is best known for his unique 28-year-long association with Federico Fellini and his popular and prolific musical work (he composed 143 scores) for film and television.

Almost all of the music used in Fellini's films from 1951 until 1979, were written or chosen by Rota. Simple, melodious, stanzaic, and, almost always, diatonic formulation characterizes the orchestration of many of his scores for Fellini. Due to Fellini's fragmentary style, Rota's compositions became the unifying force which gave continuity to Fellini's films. For Fellini, Rota never wrote a pure accompaniment to the action nor did his music only represent a few underlying emotional or dramatic moments. His music always contributed to the classification of the structure, of the characters, of the similarities between various situations, of the bond (often not explicit) between the facts and the action. It maintained an undisputed autonomy that paralleled the role and the value of the scenic action and narration. Fellini, because of his limited knowledge of music and because of his appreciation for Rota's talent, gave the composer creative control of the musical scores. To acquire a certain rhythm and to create a certain atmosphere for a scene, Fellini often filmed to Rota's music or to the music he had chosen. The director would simply suggest a sentiment or situation to Rota and Rota would spontaneously compose something which reflected and clarified the director's intent.

Rota, a child prodigy, was classically trained in composition and piano and composed his first oratorio, The Childhood of John the Baptist , at age 11. Toscanini and D'Annunzio admired his work and became his patrons. He studied under Ildebrano Pizzetti and Alfredo Cassela, and at the Milan Conservatory, the Academy of Santa Cecilia in Rome, and from 1930–32, the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. There he studied composition under Rosaria Scalero. Through her, he became familiar with the historic development of various styles and musical forms. This knowledge later enabled Rota to write for almost any period or in any style of music and contributed to his success as a composer for film. While at the Curtis Institute, he met and became friends with Aaron Copland, who inspired Rota's interest in film. He warned Rota not to assume the prejudice and the snobbish attitude that music written for film was not to be taken seriously and was simply silly enjoyment. He also became familiar with American music and musicians like Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, and George Gershwin. Rota's citation, in Amarcord , of the song "Stormy Weather" reflects American music's influence on him.

In 1931 he composed his first film score for Treno popolare , directed by Raffaello Matarazzo. This was the only score he wrote in the 1930s. The film was a critical failure and Rota did not want to be associated with it. He feared his career in film was finished, and decided to establish himself as a "serious" composer. From 1934 until 1937, he wrote mainly chamber music and his college thesis, and he taught music in a high school in Taranto. In 1939, he began teaching composition at the Bari Conservatory.

During the 1940s and 1950s he was the principal composer for Lux Films and was often forced to collaborate on "shoddy" films; however, it was during this time that he began subtly combining leitmotif with symphonic structure to comment, in a melodious way, on characters and situations. He achieved fame as a composer for epoch films, and also gained recognition for his operas.

From 1951 until his death, his work with directors like Fellini, Franco Zeffirelli, Luchino Visconti, and Francis Ford Coppola brought him additional fame. Rota once said he felt it unfortunate that a film score was, usually, only a "secondary" element of a film, "subservient" to the visual images, "a mere tool, used to recall and give credence to the images and the emotions those images try to evoke."

Rota's critics often called him unoriginal, "a mimic" with a facility musically to reproduce a mood or ambience of a specific period. Many critics called him too melodious to be taken seriously. In reference to these criticisms, Rota responded: "Originality can not necessarily be found in a new syntax or new musical grammar. Actually, originality of music is in its substance, in the message it contains, not in its exterior form; that is, it must have canons of immediacy. If something is said to be melodic, who fears that it relates to a theme or a period in history? Simple melody brings up easy relationships, revelations, and derivations. It is a silly fear and anticultural. Every idea and inspiration has precise roots. Nothing comes from nothing."

In 1972 he was nominated for an Oscar for his score for The Godfather ; however, someone unjustly accused him of plagiarism. He protested this accusation and the charges were dropped because the music from which the theme song had been derived was a song he had written in 1946. Then in 1974 he won an Oscar for The Godfather, Part II . Besides composing popular scores for film and television, he wrote four symphonies, eight operas, ballet scores, concertos, and other orchestral work.

—Suzanne Thomas

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: