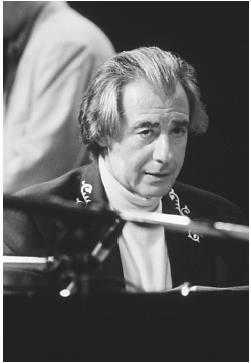

Lalo Schifrin - Writer

Composer. Nationality: Argentinian. Born: Buenos Aires, 21 June 1932. Education: Attended Paris Conservatoire; studied the violin; also studied with Juan Carlos Paz and Messiaen. Career: Organized his own jazz group; arranger for Zavier Cugat; worked with Dizzy Gillespie in the United States; composer for films from 1964, and for TV series The Partners , 1971–72, Planet of the Apes , 1974, Petrocelli , 1974, Bronk , 1975–76, Starsky and Hutch , 1975–79, and Most Wanted , 1976–77, the theme-songs for many series (including Mission Impossible ), and the mini-series Princess Daisy , 1983, Hollywood Wives , 1985, and A.D. , 1985; also composer for orchestra and jazz groups; has taught composition, University of California, Los Angeles. Awards: Grammy Award for Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or Television Show, for Mission: Impossible , 1966; Imagen Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, 1999.

Address: 710 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills, California 90210, U.S.A.

Films as Composer:

- 1964

-

Rhino! (Tors); See How They Run (Rich); Les Félins ( The Love Cage ; Joy House ) (Clement)

- 1965

-

Once a Thief (Nelson); The Cincinnati Kid (Jewison); The Liquidator (Cardiff); Dark Intruder (Hart)

- 1966

-

I Deal in Danger (Grauman); Blindfold (Dunne); Way . . . Way Out (Douglas); Murderers' Row (Levin); The Doomsday Flight (Graham)

- 1967

-

The Venetian Affair (Thorpe); Sullivan's Empire (Hart and Carr); Who's Minding the Mint? (Morris); Cool Hand Luke (Rosenberg); The President's Analyst (Flicker); How I Spent My Summer Vacation (Hale)

- 1968

-

The Fox (Rydell); Sol Madrid (Hutton); Where Angels Go . . . Trouble Follows! (Neilson); The Brotherhood (Ritt); Bullitt (Yates); Coogan's Bluff (Siegel); Hell in the Pacific (Boorman); Deadly Roulette (Hale); The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Kauffman); Mission Impossible versus the Mob (Stanley)

- 1969

-

Che! (Fleischer); Eye of the Cat (Rich); The Young Lawyers (Hart)

- 1970

-

Kelly's Heroes (Hutton); Imago (Bosnick); Pussycat, Pussycat, I Love You (Amateau); WUSA (Rosenberg); I Love My Wife (Stuart); The Mask of Sheba (Rich); The Aquarians (MacDougall)

- 1971

-

THX 1138 (Lucas); Pretty Maids All in a Row (Vadim); The Beguiled (Siegel); Escape (Moxey); Earth II (Gries)

- 1972

-

The Neptune Factor ( The Neptune Disaster ) (Petrie); Dirty Harry (Siegel); The Wrath of God (Nelson); Prime Cut (Ritchie); Welcome Home, Johnny Bristol (McGowan); Joe Kidd (J. Sturges)

- 1973

-

Rage (Scott); Magnum Force (Post); Enter the Dragon (Clouse); Charley Varrick (Siegel); St. Ives (Lee Thompson); Hunter (Horn); Hit (Furie); Harry in Your Pocket (Geller)

- 1974

-

Night Games (Taylor); Golden Needles (Clouse)

- 1975

-

Delancey Street: The Crisis Within (Frawley); Starsky and Hutch (Shear); The Four Musketeers (Lester); Foster and Laurie (Moxey); Guilty or Innocent: The Sam Sheppard Murder Case (Lewis); The Master Gunfighter (Laughlin)

- 1976

-

Man on a Swing (Perry); The Eagle Has Landed (J. Sturges); Sky Riders (Hickox); Special Delivery (Wendkos); Voyage of the Damned (Rosenberg); Brenda Starr (Stuart); Day of the Animals (Girdler)

- 1977

-

Rollercoaster (Goldstone); Good Against Evil (Wendkos)

- 1978

-

Love and Bullets (Rosenberg); Telefon (Siegel); The Manitou (Girdler); The Return from Witch Mountain (Hough); The President's Mistress (Moxey); The Nativity (Kowalski); The Cat from Outer Space (Tokar); Nunzio (Williams)

- 1979

-

Escape to Athena (Cosmatos); The Amityville Horror (Rosenberg); Institute for Revenge (Annakin); Boulevard Nights (Pressman); The Concorde—Airport '79 ( Airport '80— The Concorde ) (Rich)

- 1980

-

Loophole (Quested); Brubaker (Rosenberg); Serial (Persky); The Big Brawl (Clouse); The Nude Bomb (Donner); The Competition (Oliansky)

- 1981

-

Buddy Buddy (Wilder); Caveman (Gottlieb); When Time Ran Out ( Earth's Final Fury ) (Goldstone); La pelle ( The Skin ) (Cavani); Las viernes de la eternidad ( The Fridays of Eternity ) (Olivera); Chicago Story (London)

- 1982

-

The Seduction (Schmoeller); A Stranger Is Watching (Cunningham); Class of 1984 (Lester); Amityville II: The Possession (Damiani); Victims (Freedman); Fast-Walking (Harris); Falcon's Gold ( Robbers of the Sacred Mountain ) (Schulz)

- 1983

-

Starflight One: The Plane That Couldn't Land (Jameson); The Sting II (Kagan); Doctor Detroit (Pressman); The Osterman Weekend (Peckinpah); Rita Hayworth, the Love Goddess (Goldstone); Sudden Impact (Eastwood)

- 1984

-

Tank (Chomsky); The Mean Season (Borsos); Spraggue (Elikann)

- 1985

-

Bad Medicine (Miller); The New Kids (Cunningham)

- 1986

-

Black Moon Rising (Cokliss); Beverly Hills Madam (Hart—for TV); The Ladies Club (A. Allen)

- 1987

-

The Fourth Protocol (Mackenzie); The Silence at Bethany (Oliansky)

- 1988

-

Berlin Blues (Franco); The Dead Pool (Van Horn); Little Sweetheart (Simmons—for TV); Return From the River Kwai (McLaglen)

- 1989

-

Return to the River Kwai (McLaglen)

- 1990

-

Naked Tango (Schrader); Face to Face (Antonio)

- 1991

-

FX2: The Deadly Art of Illusion (Franklin)

- 1993

-

The Beverly Hillbillies (Spheeris)

- 1996

-

Mission: Impossible (Bay) (theme); Manhattan Merengue! (Vasquez-video)

- 1997

-

Money Talks (Ratner)

- 1998

-

Something to Believe In (Hough); Tango (Saura); Rush Hour (Ratner)

- 2000

-

Mission: Impossible II (Woo) (theme); Jack of All Trades

Publications

By SCHIFRIN: articles—

In Knowing the Score by Irwin Bazelon, New York, 1975.

Photoplay (London), February 1977.

On SCHIFRIN: articles—

Films and Filming (London), August 1968.

Thomas, Tony, in Music for the Movies , South Brunswick, New Jersey, 1973.

Ecran (Paris), September 1975.

Cook, Page, "The Sound Track," in Films in Review (US), October 1977.

Ciné Revue (Paris), 6 April 1978.

Score (Lelystad, Netherlands), September 1979.

New Zealand Film Music Bulletin (Invercargill), February 1983.

Soundtrack! (Hollywood), June 1983.

Soundtrack! (Hollywood), September 1983.

* * *

Because he has bridged so successfully the worlds of traditional and film music, Lalo Schifrin is undoubtedly the most important film composer of the post-Mancini and post- Psycho era. During the height of the Hollywood studio period, film underscoring was heavily indebted to Romantic, basically symphonic sources, with a pronounced emphasis on melodramatic principles, that is, the music was meant to key the emotionality of the scene (and was thus more prominent in genres, like the woman's picture, where emotionality was more at issue). Though these were "unheard melodies," to borrow Claudia Gorbman's phrase, there was no doubt that the underscoring composed and orchestrated by the Franz Waxmans and Max Steiners of the period (with often a substantial debt to Tchaichovsky or Chopin) was in fact music in the obvious, accepted sense of that term. In the fifties and sixties, however, the nature of underscoring changed as its "musical" elements became increasingly assimilated to other aspects of sound design. Henry Mancini's jazz scorings are an early example of the trend, while Bernard Herrmann's shrieking violins for the shower sequence in Psycho problematize the separation of music—organized sound—from other types of expressive sound effects. What is interesting, of course, is that art music of the same period was moving in more or less an identical direction, away from traditional harmonic forms of organization toward aleatory and serial approaches to the design of music.

Schifrin, the son of a concertmaster, rebelled at an early age from his father's rigid tastes (no Wagner or even Debussy allowed) and went to France to study (having won a scholarship to the prestigious Paris Conservatoire), but really in order to learn more about jazz. There Schifrin played with prominent jazz musicians such as Chet Baker, but developed eclectic tastes in modern, especially popular music. Returning to Argentina, he put together a "big band" a la Count Basie and became hugely successful. At the same time, he indulged his interests for more traditional music, writing chamber music, compositions for ballet, and even symphonies. Schifrin represented Argentina in the Third International Jazz Festival, and soon after, in 1958, moved to New York at the invitation of Dizzy Gillespie, who had heard his band during a South American tour. Schifrin played with Gillespie for three years before accepting the offer of MGM Records to begin a Hollywood career. Within a short while, he had become the most prominent and productive member of a new generation of film composers.

One of the factors contributing to his success, which is witnessed in his huge number of film credits, is that Schifrin has always accepted the subsidiary role of music within the mixed, multi-track construction of the medium. This is not to say that his musical effects, almost always an eclectic mix of techniques, genres, and modes, have not been noteworthy in themselves. In The Hellstrom Chronicles , for example, a pseudo-scentific jeremiad that predicts how insects will take over the earth, Schifrin used a very avant-garde mix of aleatory, electronic, and serial techniques to create music that was expressive both of the film's main characters—the unstoppable hordes of ravening insects—and the film's strident, uncomfortable message. No one who has seen and listened to the film could forget the terrifying effect created by Schifrin's loud electronic sounds, synchronized piano effects, and unpredictable moments of loud percussion. But is this music or sound effects? Schifrin and sound designers such as Walter Murch, in any event, share much in common. For Hell in the Pacific , an arty, "psychological" war film, Schifrin designed a sequence where the Japanese soldier marooned on a Pacific Island hears loud cicadas, which then blend into "music" (two high-pitched, very loud piccolos) that segues into more traditional scoring. Similarly, for Bullitt Schifrin scored the famous car chase sequence by using music—a hard-driving jazz theme—which subtly fades into more traditional sound effects—screeching tires, squealing breaks. Compare the similar uses of expressive noise employed by Murch in the sequence in The Conversation where the snooping detective finds the bloody traces of a murder in a hotel bathroom. The two masters of modern sound design, Murch and Schifrin, even had a chance to collaborate, on George Lucas's science fiction film THX 1138 , which has perhaps the most complex and expressive sound of any film during the seventies.

Of course, Schifrin is also expert at less subtle kinds of scoring, particularly at composing what are now known as "action themes." His action theme scoring for the TV show Mission: Impossible is probably one of the most recognizable on the contemporary music scene (recently recycled for the feature film remake of the series) and it is built on a very simple theme with a prominent rhythmic structure and unusual instrumentation (very prominent bongo drums, a kind of tribute to Mancini-esque fifties jazz scorings). Though more traditional symphonic underscorers still find work in Hollywood—John Williams is by far the most successful—the kind of expressive underscoring perfected by Schifrin has defined what film music has largely become in the post-studio era. If his career has declined somewhat in the nineties, his pervasive influence on the presence of sound and music in the commercial film has not.

—R. Barton Palmer

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: