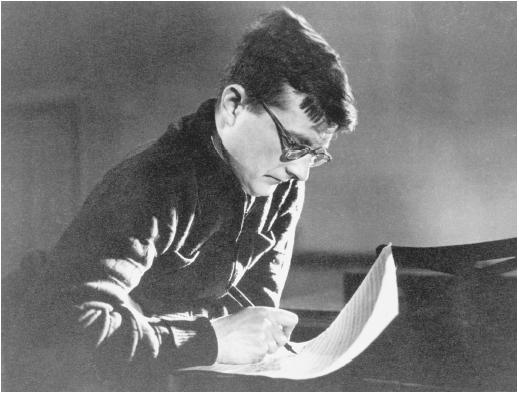

Dmitri Shostakovich - Writer

Composer.

Nationality:

Russian.

Born:

Dmitri Dimitriyevich Shostakovich in St. Petersburg, 25 September 1906.

Education:

Studied under Nikolayev, Steinberg, and Glazunov at the Leningrad

Conservatory, 1919–25.

Career:

Important compositions performed in mid-1920s; 1929—first film

score, for

The New Babylon

; composer of orchestra and stage works.

Died:

In Moscow, 9 August 1975.

Films as Composer:

- 1929

-

Novyi Vavilon ( The New Babylon ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg)

- 1931

-

Odna ( Alone ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg); Zlaty gori ( Golden Hills ) (Yutkevich)

- 1932

-

Vstrechnyi ( Counterplan ) (Yutkevich and Ermler)

- 1935

-

Yunost Maxima ( The Youth of Maxim ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg); Podrugi ( Girl Friends ) (Arnstam)

- 1937

-

Vozvrashcheniye Maxima ( The Return of Maxim ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg); Volochayevskiye dni ( The Days of Volotchayev ) (G. and S. Vasiliev)

- 1938

-

Chelovek s ruzhyom ( The Man with a Gun ) (Yutkevich)

- 1938–39

-

Velikii grazhdanin ( A Great Citizen ) (Ermler—2 parts)

- 1939

-

Vyborgskaya storona ( New Horizons ; The Vyborg Side ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg)

- 1944

-

Zoya (Arnstam)

- 1947

-

Molodaya gvardiya ( Young Guard ) (Gerasimov); Pirogov (Kozintsev)

- 1948

-

Michurin (Dovzhenko)

- 1949

-

Vstrecha na Elbe ( Encounter at the Elbe ) (Alexandrov); Padeniye Berlina ( The Fall of Berlin ) (Chiaureli)

- 1952

-

Nezabyvayemyi 1919-god ( The Unforgettable Year 1919 ) (Chiaureli)

- 1953

-

Belinsky (Kozintsev)

- 1954

-

Das Lied der Ströme ( Songs of the Rivers ) (Ivens)

- 1955

-

Ovod ( The Gadfly ) (Fainzimmer)

- 1956

-

Prostiye lyudi ( Simple People ) (Kozintsev and Trauberg—produced 1945); Pervye eshelon ( The First Echelon ) (Kalatazov)

- 1959

-

Khovanshchina (Stroyeva)

- 1960

-

Pyat dney—pyat nochey ( Five Days—Five Nights ) (Arnstam)

- 1962

-

I sequestrati di Altona ( The Condemned of Altona ) (De Sica)

- 1963

-

Cheryomushki ( Song over Moscow ) (Rappaport); Hamlet (Kozintsev)

- 1967

-

Katerina Izmailova (Shapiro) (+ sc); Oktiabr ( October ) (Eisenstein) (new version); Sofiya Perovskaya (Arnstam)

- 1971

-

Korol Lir ( King Lear ) (Kozintsev)

Publications

By SHOSTAKOVICH: books—

The Power of Music , New York, 1968.

Testimony: The Memoirs of Shostakovich , edited by Solomon Volkov, New York, 1979.

Dimitry Shostakovich: About Himself and His Times , edited by L. Grigoryev and Yakov Platek, Moscow, 1981.

Pisma k drugu: Dimitrii Shostakovich [Correspondence. Selections], with commentary by I. D. Glikmana, Moscow, DSCH, 1993.

On SHOSTAKOVICH: books—

Seroff, Victor, Dimitry Shostakovich , New York, 1943, revised edition 1970.

Rabinovich, D., Dimitry Shostakovich, Composer , London, 1959.

Kay, Norman, Shostakovich , London, 1971.

Roseberry, Eric, Shostakovich , London, 1981.

Hulma, Derek C., Dimitry Shostakovich: Catalogue, Bibliography, and Discography , Muir of Ord, Scotland, 1982.

Norris, Christopher, Shostakovich , London, 1982.

Martynov, Ivan I., Dimitri Shostakovich: The Man & His Work: Music Book Index , Temecula, 1993.

Meyer, Krzysztof, Dimitri Chostakovitch , Paris, Fayard, 1994.

Wilson, Elizabeth, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered , Princeton, NJ, University Press, 1994.

Shostakovich Studies , edited by David Fanning, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

On SHOSTAKOVICH: articles—

Soviet Film (Moscow), May 1964.

Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), July 1967.

Soviet Film (Moscow), August 1967.

Soviet Film (Moscow), September 1976.

Filmcritica (Rome), May-June 1980.

Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), December 1981.

Cineforum , vol. 31, no. 308, 1991.

DSCH Journal , no. 1, Summer 1994.

Atlantic Monthly , vol. 275, February 1995

Commentary , vol. 99, February, 1995.

Index on Censorship , November-December 1998.

Commentary , vo1. 107, June 1999.

Commentary , vol. 108, October 1999.

Mosaic (Winnipeg), December 1999.

Forbes , 20 March 2000.

* * *

No other major composer devoted more of his career to film music than Dmitri Shostakovich. Altogether he composed scores for 36 films, from The New Babylon in 1929 to King Lear in 1971. (He also started work on a further project, The Envoys of Eternity , but the film was never realised.) Movies provided an invaluable source of income for Shostakovich at those times when he fell into official disfavour, but he also had a genuine love of cinema. One of his earliest jobs was providing piano accompaniment in a movie house; he was sacked for laughing so much at a Hollywood comedy that he forgot to play.

Since he was sensitive to the specific demands of the medium, Shostakovich's film music tends to be written in a more accessible idiom than most of his orchestral or chamber works. But there was never anything careless or slipshod about it. He brought to the task unfailingly scrupulous craftsmanship, and once when asked about the subject quoted a remark of Gogol's about writing for children: "The same as for adults, only better." And in his film scores, no less than in the symphonies and string quartets, can be seen every aspect of his complex and often paradoxical musical personality.

His first score, to accompany Kozintsev and Trauberg's silent New Babylon , is full of the parodistic, nose-thumbing humour that characterises so much of his early work. Scenes of the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War are accompanied, not by the expected martial rhythms, but by oompah circus tunes and pratfalls from the percussion. Irreverent quotation figures strongly, with Offenbach's Orpheus can-can at one point interwoven with the Marseillaise. Shostakovich's approach perfectly matched the film's sardonic expressionism, but the score aroused widespread hostility and many cinemas refused to use it.

Undeterred, he followed similar principles in his first sound film, Alone , also for Kozintsev and Trauberg. Shostakovich established a lifelong rapport with Kozintsev, scoring all his sound films except Don Quixote . The two were in complete agreement on the essential function of film music: not to illustrate the action but to add an entirely new dimension, often running in counterpoint to the visuals or even undercutting them.

Shostakovich's keen dramatic sense, and his mercurial skill in juxtaposing frivolity with despair—often using one to suggest the other—served him particularly well in his film music. To say that much of it is trivial is no condemnation: he valued trivial music, granting it a legitimate role in even his most serious symphonic compositions. Few composers could have been better suited to animated films, and it is a great shame that Mikhail Tsekhanovsky's feature-length "cartoon comic-opera," The Tale of the Priest and His Servant Balda , was never completed (and the footage subsequently lost). Luckily, Shostakovich's exuberant score survives, so vivid that one can almost see the visuals it accompanied.

For the patriotic films of the 1940s and 1950s Shostakovich supplied more conventional material, although an undercurrent of scepticism and personal anguish, as in the 7th and 8th Symphonies, prevented him falling back on bombastic Soviet cliché. His score for Five Days—Five Nights creates a poignant vision of the shattered city of Dresden, with pity for war's victims (of whatever nationality) and hope for the future expressed in a passionate orchestral climax built around a theme from Beethoven's Choral Symphony.

Shostakovich's film music also gave vent to the romantic side of his character—though tempered, once again, by a pervasive sense of irony. For The Unforgettable Year 1919 he devised a single-movement piano concerto that rivals Addinsell's Warsaw Concerto in its lush Rachmaninovian pastiche. The Gadfly , a period swashbuckler set in Austrian-occupied Italy, inspired one of his most tuneful and approachable scores, including a Romance that became something of a popular hit as theme music for the British TV serial Reilly, Ace of Spies .

The sparse textures and sombre tones of Shostakovich's late style colour his scores for Kozintsev's two powerful Shakespeare films, Hamlet and King Lear . Hamlet is full of obsessive, driving rhythms, punctuated by fierce outbursts of percussion, while passages of high skittering woodwind suggest mental disturbance. The music for Lear is even darker, with slow rumbling brass chorales reflecting the inexorable disaster overtaking king and country alike. Both scores do full justice to Kozintsev's epic conception of the plays, and bring Shostakovich's career as a film composer to an impressive conclusion.

—Philip Kemp

I'm looking for the music of the film Novyi Vavilon (The New Babylon - Kozintsev and Trauberg)

Can somebody helps me?

Thanks

Luisina (argentina)