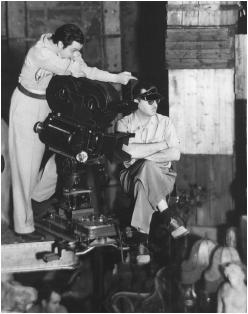

Gregg Toland - Writer

Cinematographer. Nationality: American. Born: Charleston, Illinois, 29 May 1904. Military Service: 1941–45—photographer and camera designer for Navy Photographic Unit and Office of Strategic Services. Family: Married the actress Virginia Thorpe, 1945. Career: Messenger boy, then camera assistant to Al St. John at William Fox Studio; later, assistant to Arthur Edeson; 1926—began

Films as Co-Cinematographer with George Barnes:

- 1929

-

This Is Heaven (Santell); Bulldog Drummond (Jones); Condemned (Ruggles); The Trespasser (Goulding)

- 1930

-

Whoopee! (Freeland) (co); Raffles (D'Arrast); One Heavenly Night (Fitzmaurice)

Films as Cinematographer:

- 1931

-

The Devil to Pay (Fitzmaurice); The Unholy Garden (Fitzmaurice); Indiscreet (McCarey) (co); Tonight or Never (LeRoy); Palmy Days (Sutherland)

- 1932

-

Playgirl (Enright); Man Wanted (Dieterle); The Tenderfoot (Enright); The Washington Masquerade (Brabin); The Kid from Spain (McCarey)

- 1933

-

The Nuisance (Conway); Tugboat Annie (LeRoy); The Masquerader (Wallace); Roman Scandals (Tuttle)

- 1934

-

Jazz River (Seitz); Forsaking All Others (Van Dyke) (co); Nana (Arzner); We Live Again (Mamoulian)

- 1935

-

The Wedding Night (Vidor); Public Hero No. 1 (Ruben); Les Miserables (Boleslawsky); Mad Love (Freund) (co); The Dark Angel (Franklin); Splendor (Nugent)

- 1936

-

Strike Me Pink (Taurog) (co); These Three (Wyler); Come and Get It (Hawks and Wyler) (co); The Road to Glory (Hawks); Beloved Enemy (Potter)

- 1937

-

History Is Made at Night (Borzage); Woman Chases Man (Blystone); Dead End (Wyler)

- 1938

-

The Goldwyn Follies (Marshall); Kidnapped (Werker); The Cowboy and the Lady (Potter)

- 1939

-

Wuthering Heights (Wyler); They Shall Have Music (Mayo); Intermezzo: A Love Story (Ratoff)

- 1940

-

Raffles (Wood); The Grapes of Wrath (Ford); The Westerner (Wyler); The Long Voyage Home (Ford)

- 1941

-

Citizen Kane (Welles); The Little Foxes (Wyler); Ball of Fire (Hawks)

- 1943

-

December 7th (+ co-d); The Outlaw (Hughes)

- 1946

-

The Kid from Brooklyn (McLeod); Song of the South (Foster and Jackson); The Best Years of Our Lives (Wyler)

- 1947

-

The Bishop's Wife (Koster); A Song Is Born (Hawks)

- 1948

-

Enchantment (Reis)

Publications

By TOLAND: articles—

On Citizen Kane in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1941.

On Citizen Kane in Popular Photoplay (New York), June 1941.

"Motion Picture Cameraman," in Theatre Arts (New York), February 1941.

Revue du Cinéma (Paris), January 1947.

Screenwriter (London), December 1947.

With G. Turner, "Xanadu in Review: Citizen Kane Turns 50," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), August 1991.

On TOLAND: articles—

Blaisdell, G., " Citizen Kane 's New Technique," in Movie-Makers , March 1941, reprinted in Classic Film Collector (Muscatine, Iowa), Winter 1977.

Alekan, Henri, in Ecran (Paris), 30 November 1948.

Slocombe, Douglas, and William Wyler, in Sequence (London), Summer 1949, also letter in Autumn 1949.

Film (New York), September 1953.

Mitchell, G., in Films in Review (New York), December 1956.

Filmmaker's Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), May 1971.

Film Comment (New York), Summer 1972.

Focus on Film (London), no. 13, 1973.

Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 15, no. 2, 1973.

Filme (Berlin), no. 6, 1980.

Film Psychology Review (Salem, New York), Summer-Fall 1980.

Carringer, R.L., on Toland and Welles in Critical Inquiry (Chicago), no. 4, 1982.

Turner, George, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), November 1982, corrections in letter, January 1983.

Allen, R., in Framework (Norwich, Norfolk), Summer 1983.

Skinner, James M., " December 7 : Filmic Myth Masquerading as Historical Fact," in Journal of Military History , October 1991.

Turner, George, " Sharp Practice: The Innovators 1940–1950 ," in Sight and Sound (London), July 1999.

* * *

Gregg Toland was one of the greatest cinematographers of the Hollywood studio era—if not the greatest. Much more than a competent technician, Toland was a visual stylist and an innovator. He often supervised the set construction on his films, and he always worked closely with his directors to plan lighting and camerawork that would go beyond the technical requirements of filmmaking to create the proper mood for a scene.

Toland's most productive association with a director was his sixfilm collaboration with William Wyler. It was on the Wyler films of the late 1930s that the cinematographer began experimenting with the composition-in-depth and deep-focus photography for which he is best known. Composition-in-depth is the arrangement of characters and action on several planes within the frame at once. The different planes need not all be in focus simultaneously for composition-in-depth to be effective; if, however, foreground, middleground, and background are all in sharp focus at the same time, this effect is called deep-focus photography.

Wyler liked to use long takes, long shots, and composition-in-depth: he preferred to create dramatic tension by spreading his actors out across the frame and on different planes within the frame, rather than by cutting back and forth between them. In The Little Foxes , for example, the death of Horace involves a very lengthy shot and two planes of action. In the shot the focus stays on Regina, who sits motionless in the foreground, while the paralyzed Horace struggles and then dies of a heart attack—out of focus—on the stairs in the background.

Toland experimented with composition-in-depth and deep focus on other films—John Ford's The Long Voyage Home , for example—and then perfected the deep-focus technique on Orson Welles's masterpiece, Citizen Kane . Toland's use of high-intensity arc lamps and the newly available light sensitive Eastman Super XX film stock allowed him to close down the aperture of his 24mm lens to f8 or less; the combination of the wide-angle lens and narrow aperture gave Toland sharp focus on objects from five to 50 feet or more away from the camera.

Welles and Toland used deep focus extensively in Citizen Kane —sometimes as a functional alternative to shot-reaction shot editing, and sometimes expressively, to create a mood or a visual metaphor. In one shot early in the film, Charlie Kane's mother and a banker, in the foreground, sign an agreement that will allow young Charlie to be taken away from his parents and later inherit a fortune; Charlie's father, uncertain about the agreement, paces back and forth in the middleground; Charlie, seen through a window, plays unsuspectingly in the snow in the background. Thus, one of the film's themes—Kane's alienation from the others—is established visually in this early scene.

After Citizen Kane —his crowning achievement—Toland continued his fine work on films such as Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives , until his distinguished career was cut short by his premature death in 1948.

—Clyde Kelly Dunagan

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: