Walter Wanger - Writer

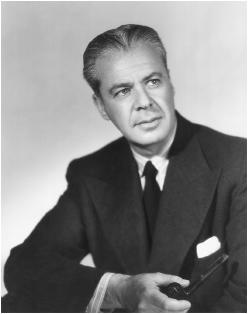

Producer. Nationality: American. Born: Walter Feuchtwanger in San Francisco, California, 11 July 1894 (some sources give 16 October). Education: Attended Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. Military Service: Served in Army Intelligence during World War I, and on President Wilson's staff at Paris Peace Conference. Family: Married the actress Joan Bennett (second marriage),

Films as Producer:

- 1929

-

The Cocoanuts (Santley and Florey); Applause (Mamoulian) (co)

- 1932

-

The Bitter Tea of General Yen (Capra); Washington Merry-Go-Round (Cruze)

- 1933

-

Another Language (Griffith) (production associate); Going Hollywood (Walsh); Queen Christina (Mamoulian); Gabriel over the White House (La Cava)

- 1934

-

The President Vanishes (Wellman); Stamboul Quest (Wood)

- 1935

-

Private Worlds (La Cava); Mary Burns, Fugitive (Howard); Shanghai (Flood); Every Night at Eight (Walsh); Smart Girl (Scotto)

- 1936

-

Big Brown Eyes (Walsh); Spendthrift (Walsh); The Moon's Our Home (Seiter); Fatal Lady (Ludwig); The Case Against Mrs. Ames (Seiter); Palm Springs (Scotto); Her Master's Voice (Santley); Sabotage (Hitchcock); The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (Hathaway)

- 1937

-

You Only Live Once (F. Lang); Stand-In (Garnett); 52nd Street (Young); Vogues of 1938 ( Walter Wanger's Vogues of 1938 ) (Cummings)

- 1938

-

I Met My Love Again (Ripley and Logan); Blockade (Dieterle); Algiers (Cromwell); Trade Winds (Garnett)

- 1939

-

Winter Carnival (Reisner); Stagecoach (Ford) (exec); Eternally Yours (Garnett)

- 1940

-

The Long Voyage Home (Ford); Slightly Honorable (Garnett); The House Across the Bay (Mayo); Foreign Correspondent (Hitchcock)

- 1941

-

Sundown (Hathaway)

- 1942

-

Eagle Squadron (Lubin); Arabian Nights (Rawlins)

- 1943

-

We've Never Been Licked (Rawlins); Gung Ho! (Enright)

- 1944

-

Ladies Courageous (Rawlins)

- 1945

-

Salome, Where She Danced (Lamont); Scarlet Street (F. Lang) (exec)

- 1946

-

Canyon Passage (Tourneur); A Night in Paradise (Lubin)

- 1947

-

The Lost Moment (Gabel); Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman ( A Woman Destroyed ) (Heisler)

- 1948

-

The Secret beyond the Door (F. Lang); Joan of Arc (Fleming); Tap Roots (Marshall)

- 1949

-

Tulsa (Heisler); The Reckless Moment (Ophüls); Reign of Terror ( The Black Book ) (A. Mann)

- 1952

-

Aladdin and His Lamp (Landers); Battle Zone (Selander); Lady in the Iron Mask (Murphy) (co)

- 1953

-

Kansas Pacific (Nazarro); Fort Vengeance (Selander)

- 1954

-

Riot in Cell Block 11 (Siegel); The Adventures of Hajii Baba (Weis)

- 1956

-

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Siegel); Navy Wife (Bernds)

- 1958

-

I Want to Live! (Wise)

- 1963

-

Cleopatra (Mankiewicz) (replaced by Zanuck)

Publications

By WANGER: book—

With Joe Hyams, My Life with "Cleopatra," New York, 1963.

On WANGER: book—

Bernstein, Matthew, Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent , Minneapolis, 2000.

On WANGER: articles—

Films and Filming (London), December 1960.

Brownlow, Kevin, in Film (London), no. 39, 1964.

Rosenberg, Bernard, and Harry Silverstein, in The Real Tinsel , New York, 1970.

Cinématographe (Paris), May 1984.

Velvet Light Trap (Madison, Wisconsin), no. 22, 1986.

Velvet Light Trap (Madison, Wisconsin), no. 28, Fall 1991.

Doherty, Thomas, "Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1996.

* * *

Leaving aside the headline-grabbing incidents that blighted the last decade of his career, Walter Wanger stands as the epitome of the inspirational Hollywood producer, committed to artistry as much as profit, provocation as much as pleasure. Renowned and respected for his hands-off approach, entrusting his collaborators with creative freedom, contributing his ideas as suggestions rather than dictates, Wanger enjoyed fruitful partnerships with the likes of Fritz Lang, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock and Don Siegel. Working in a wide variety of genres and styles, the biggest constant in his career is an enduring concern with the blind, dehumanising force of legal/social retribution and the way a decent person can be hounded to the grave by one minor indiscretion or unlucky break. Cannily trading off his "serious" efforts ( Scarlet Street ) with pure box-office hokum ( Salome Where She Danced ), Wanger's instincts were skewed only by a tendency towards literary awe (placing troubled talents F. Scott Fitzgerald and Dorothy Parker under contract despite a demonstrable lack of screenwriting ability). It says something about his ability that Wanger's avowed dislike of being second best in anything comes across not as typical front-office arrogance but a simple statement of fact.

Employed by most of the big studios at one time or another, Wanger first came to prominence at Paramount, facilitating the Marx Brothers' big screen debut in The Cocoanuts and director Rouben Mamoulian's striking first film, the location-shot vaudeville star-loses-love-of-daughter melodrama Applause . A two-film stint at Columbia included Frank Capra's still enticing miscegenation fantasy The Bitter Tea of General Yen. Pausing at MGM long enough to endorse Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal (in Gabriel over the White House ) and produce the definitive Greta Garbo vehicle, Mamoulian's Queen Christina , Wanger settled at Paramount in the mid-1930s, becoming acquainted with wife-to-be Joan Bennett (costar of the medical drama Private Worlds ). The same year he brought out his first miscarriage-of-justice melodrama, Mary Burns, Fugitive , with Sylvia Sidney as the former gangster's moll undone by circumstance and prejudice. Having teamed Sidney with Henry Fonda on the technicolour hillbilly drama Trail of the Lonesome Pine , Wanger reunited the stars, regular writer Graham Baker and regular cameraman Leon Shamroy for the independently produced You Only Live Once. Under Fritz Lang's unflinching eye, the story of a petty crook framed for murder took on a tragic dimension, the gripping victimised-love-on-the-run plot undermined only by the sentimental Hays Office friendly conclusion. Confident on home ground, Wanger's ambitions fell flat the following year with Blockade , a bland, laughably apolitical Spanish Civil War adventure which managed to mention neither Franco nor the Fascists as simple farmer Henry Fonda turns fighter in defense of his land.

Running with a winning streak at the end of the decade, notably the John Ford-John Wayne-Dudley Nichols team-ups Stagecoach and The Long Voyage Home (the former relocating its producer's usual outsider-prejudice theme to the Old West), Wanger found more effective antifascist propaganda in Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent , which even Joseph Goebbels had to admire. Signing on with Universal shortly after, he alternated further fighting-spirit efforts ( Sundown, Gung Ho! ) with escapism ( Arabian Nights ). The end of hostilities brought Scarlet Street , a moody noir reuniting Lang, Bennett, Edward G. Robinson, and Dan Duryea from the previous year's hit The Woman in the Window , a lighter non-Wanger thriller. Remarkable at the time for showing a murderer go officially unpunished (downtrodden clerk Robinson kills deceitful prostitute mistress Bennett; sleazy pimp Duryea goes to the chair), the film suggests that state sanctioned execution is preferable to the inner torments suffered by the now vagrant Robinson at the conclusion (in a turnaround on the usual Wanger take, no one will believe that the pathetic man is guilty).

Over the next few years, Wanger lost form, the special "moral stature" Academy Award handed out for the notorious dud Joan of Arc fooling no-one. The trash melodrama The Reckless Moment , a Columbia-backed vehicle for Bennett and James Mason, won a few European admirers, largely thanks to Max Ophüls' ultra stylish handling. There were fewer takers for the dreary Bennett-Lang psycho-melodrama The Secret beyond the Door. Already associating with downmarket outfits such as Eagle Lion, Wanger's industry standing took a rapid downward turn in 1952 when he shot Joan Bennett's agent-turned-lover in the groin. Serving his four month jail sentence in a relatively easy-going honour camp, Wanger nevertheless emerged with a burning desire to expose the corruption and injustices of the penal system and also to relaunch his career. Teaming up with poverty row exploitation specialists Allied Artists (formerly Monogram), Wanger was fortunate to be joined on Riot in Cell Block 11 by director Don Siegel, an expert in alienated, violent outsiders (here inside), and ferocious leading man Neville Brand. Riot hit home and Wanger reunited with Siegel for Invasion of the Body Snatchers , an unsurpassed nightmare fantasy on the loss of individuality. Back in demand, Wanger made a shaky return to the capital punishment debate with the based-on-fact I Want to Live! , an awkward (if award winning) vehicle for frequent collaborator Susan Hayward. In the same year he started work on a modestly budgeted historical tale, Cleopatra , a Fox-backed project for minor contract star Joan Collins. The rest is dismal history: five years worth of cast changes, director changes (Mamoulian making way for Joseph Mankiewicz), location changes, mounting costs, general chaos and financial disaster, all centred arond chronically unhealthy million-dollar-star Elizabeth Taylor. Fired by Darryl Zanuck towards the end of production, Wanger and assorted Fox personnel attempted to sue each other into the ground. For a man who once remarked that nothing was as cheap as a hit, no matter how much it cost, this career finale marked a particularly sad end.

—Daniel O'Brien

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: