Haskell Wexler - Writer

Cinematographer and Director. Nationality: American. Born: Chicago, Illinois, 6 February 1926. Education: Attended the University of Chicago. Career: Merchant seaman for four years; amateur filmmaker since his teens; made educational and industrial films for ten years; 1960—first feature film as cinematographer, The Savage Eye ; 1969—directed first feature film, Medium Cool ; mid-1970s—formed Wexler Hall Inc., with Conrad Hall, to make commercials. Awards: Academy Awards, for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , 1966, and Bound for Glory , 1976.

Films as Cinematographer:

- 1955

-

The Living City (+ d—short); Picnic (Logan) (2nd unit)

- 1959

-

Five Bold Women (Lopez-Portillo)

- 1960

-

The Savage Eye (Maddow, Meyers, and Strick); Studs Lonigan (Lerner)

- 1961

-

The Hoodlum Priest (Kershner); Angel Baby (Wendkos) (co); Jangadero (Guggenheim)

- 1962

-

T for Tumbleweed (short)

- 1963

-

A Face in the Rain (Kershner); America, America (Kazan)

- 1964

-

The Best Man (Schaffner)

- 1965

-

The Loved One (Richardson) (+ co-pr); The Bus (+ d, pr, sc)

- 1966

-

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Nichols)

- 1967

-

In the Heat of the Night (Jewison)

- 1968

-

The Thomas Crown Affair (Jewison)

- 1969

-

Medium Cool (+ d, co-pr, sc)

- 1970

-

Interviews with My Lai Veterans (Strick—short) (co); Gimme Shelter (D. & A. Maysles) (co)

- 1971

-

Brazil: A Report on Torture (+ co-d, co-pr); Interview with President Allende (+ co-d, co-pr)

- 1972

-

Trial of the Catonsville Nine (Davidson)

- 1973

-

American Graffiti (Lucas) (consultant)

- 1974

-

Introduction to the Enemy (+ co-d, co-pr, co-sc)

- 1975

-

One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest (Forman) (co)

- 1976

-

Underground (+ co-d, co-pr, co-sc); Bound for Glory (Ashby)

- 1978

-

Coming Home (Ashby); Days of Heaven (Malick)

- 1980

-

No Nukes (Schlossberg, Goldberg, and Potenza)

- 1981

-

Second Hand Hearts (Ashby)

- 1982

-

Lookin' to Get Out (Ashby); The Kid from Nowhere (Bridges) (special ph); Richard Pryor Live on the Sunset Strip (Layton)

- 1983

-

The Man Who Loved Women (Edwards); Bus II (co-d only)

- 1985

-

Latino (+ d)

- 1987

-

Matewan (Sayles)

- 1988

-

Colors (Hopper)

- 1989

-

Three Fugitives (Veber); Blaze (Shelton)

- 1990

-

Other People's Money (Jewison); The Babe (Hiller); Through the Wire (Rosenblum—for TV); To the Moon, Alice (Nelson—short)

- 1991

-

Other People's Money (Jewison)

- 1992

-

The Babe (Hiller)

- 1994

-

The Secret of Roan Inish (Sayles); Canadian Bacon (Moore)

- 1996

-

Mulholland Falls (Tamahari); The Bishop, the Warrior and Rebellion in Chiapas (Landau—doc-in-progress) (co-pr); The Rich Man's Wife (A. H. Jones)

- 1999

-

Limbo (Sayles); Bus Rider's Union

Publications

By WEXLER: articles—

Action (Hollywood), May/June 1967.

Film Quarterly (Berkeley, California), Spring 1968.

Cinéma (Paris), May 1970.

Kosmorama (Copenhagen), September 1970.

Take One (Montreal), no. 3, 1972.

Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1975.

"How to Convert a 16mm Zoom Lens into a 35mm Zoom Lens," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), January 1975.

Film Français (Paris), 23 April 1976.

On Bound for Glory in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), July 1976.

Seminar in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), June and July 1977.

Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), March 1978.

Cinématographe (Paris), March 1979.

On One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest in American Film (Washington, D.C.), September 1979.

Filme (Berlin), no. 6, 1980.

In Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers , by Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato, Berkeley, California, 1984.

Jeune Cinéma (Paris), July/August 1985.

On TV commercials in On Location (Hollywood), October 1985.

Stills (London), November 1985.

Cinéaste (New York), vol. 14, no. 3, 1986.

American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1988.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1990.

On WEXLER: articles—

Lightman, Herb A., on Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), August 1966.

Lightman, Herb A., on The Thomas Crown Affair in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), October 1968.

Film Quarterly (Berkeley, California), Winter 1969.

Chaplin (Stockholm), no. 3, 1970.

Jones, R. B., in Take One (Montreal), March/April 1970.

Film Comment (New York), Summer 1972.

Focus on Film (London), no. 13, 1973.

Film a Doba (Prague), March 1973.

Hess, J., in Jump Cut (Chicago), August/September 1975.

Cook, B., "Commercials: Another Form of Filmmaking," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1977.

Take One (Montreal), no. 2, 1978.

Goodwin, M., on Wexler and Kovacs in Moving Image (San Francisco), March/April 1982.

Film Comment (New York), March/April 1984.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), November 1991.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1993.

Entertainment Weekly (New York), 5 May 1995.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), June 1996.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), January 1997.

* * *

Haskell Wexler has worked alternately and successfully inside and outside the commercial film industry throughout his career. He has a reputation as a radical documentary filmmaker, yet he is also an Academy Award-winning Hollywood cameraman. Wexler's cinematography credits include documentaries, Hollywood features, and television commercials. The element which these various works share is Wexler's camera technique. He consciously brings his experience in documentary film to every project in which he is involved.

During the 1950s Wexler learned his craft working in the American cinéma vérité style of documentary film. His first feature was uncredited work on Irvin Kershner's Stakeout on Dope Street . Kershner also came from a documentary background. The two experimented, mixing cinéma vérité and fiction narrative conventions. The film was shot on location rather than in a studio, and hand-held cameras were used. Wexler continued to incorporate the visual techniques of documentary film into features, including two more with Kershner in subsequent years. The harsh, realistic style of such films as The Savage Eye , America, America , and The Loved One is characteristic of his early work in features.

Realism is still emphasized in Wexler's later cinematic style, although the documentary elements vary in degree from film to film. He uses nonfiction film techniques creatively to heighten the tension and mood of a narrative film. In Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , a work about intensely personal emotions, Wexler effectively uses a hand-held camera more forcefully to project the tension in some scenes. His camera work gives a gritty reality to the dust storms and shanty towns in Bound for Glory . The documentary-style interview scenes with Vietnam veterans in Coming Home remind viewers that the fictional drama represents actual issues. The realistic portrayal of the violence-ridden streets of East Los Angeles in Colors is too powerful for some viewers and even some critics.

Wexler's documentary experience is also evident in films that have a more traditional cinematic look. In Other People's Money , Wexler captures the visual reality and personality of a small New England town and its resident wire and cable company. Both are so stable and old-fashioned that the company becomes too static to deal with a Wall Street takeover. In The Babe , he visually conveys a behind-the-scenes look at baseball's dark, seedy side.

While Wexler has worked in feature films since the 1950s, he has never stopped making documentaries. The subject matter of these films has often been politically controversial—the Vietnam War, torture practices of governments, nuclear power. Because of their theater circulation, Interviews with My Lai Veterans and No Nukes are probably the best-known documentaries that Wexler has photographed. His most recent project to date is The Bishop, the Warrior and Rebellion in Chiapas , a documentary-in-progress on the current Zapatista rebellion in Mexico, directed by Saul Landau.

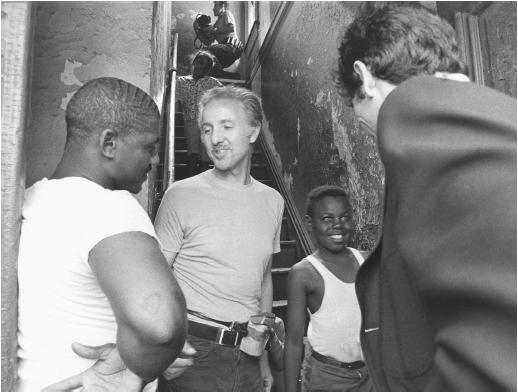

The two feature films that Wexler directed, Medium Cool and Latino , received extremely limited promotion and distribution because of their political content. Medium Cool is an examination of responsibility and accountability in the television news industry and in government set, in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic Convention. The film's form complements its themes. Wexler uses many of the conventions of reportage-style documentary film for this feature. His more recent work Latino presents a strong political position on American foreign policy in Nicaragua in the mid-80s. Wexler uses a more conventional narrative form than in Medium Cool . Documentary technique is used, as in previous features, for effect in certain scenes. Wexler decided to use a more conventional form for Latino because he felt it would appeal to contemporary audiences more than a documentary format.

—Marie Saeli

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: