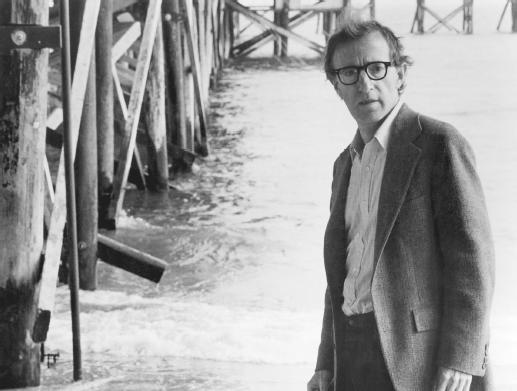

Woody Allen - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Allen Stewart Konigsberg in Brooklyn, New York, 1 December 1935. Education: Attended Midwood High School, Brooklyn; New York University, 1953; City College (now City College of the City University of New York), 1953. Family: Married 1) Harlene Rosen, 1954 (divorced); 2) Louise Lasser, 1966 (divorced); 3) Soon-Yi Previn, 1997; one daughter, Bechet Dumaine; also maintained a thirteen-year relationship with actress Mia Farrow, 1979–92; one son, Satchel, and two adopted children, one son, Moses, and one daughter, Dylan). Career: Began writing jokes for columnists and television celebrities while still in high school; joined staff of National Broadcasting Company, 1952, writing for such television comedy stars as Sid Caesar, Herb Shriner, Buddy Hackett, Art Carney, Carol Channing, and Jack Paar; also wrote for The Tonight Show and The Garry Moore Show; began performing as stand-up comedian on television and in nightclubs, 1961; hired by producer Charles Feldman to write What's New, Pussycat? , 1964; production of his play Don't Drink the Water opened on Broadway, 1966; wrote and starred in Broadway run of Play It Again, Sam , 1969–70 (filmed 1972); began collaboration with writer Marshall Brickman, 1976; wrote play The Floating Light Bulb , produced at Lincoln Center, New York, 1981. Awards: Sylvania Award, 1957, for script of The Sid Caesar Show ; Academy Awards (Oscars) from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay (co-recipient), New York Film Critics Circle Award, and National Society of Film Critics Award, all 1977, all for Annie Hall ; Britis Academy Award and New York Film Critics Award, 1979, for Manhattan ; Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, New York Film Critics Award, and Los Angeles Film Critics Award, all 1986, all for Hannah and Her Sisters. Agent : Rollins and Joffe, 130 W. 57th Street, New York, NY 10009, U.S.A. Address: 930 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10021, U.S.A.

Films as Director, Scriptwriter, and Actor:

- 1969

-

Take the Money and Run

- 1971

-

Bananas (co-sc)

- 1972

-

Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex but Were Afraid to Ask

- 1973

-

Sleeper

- 1975

-

Love and Death

- 1977

-

Annie Hall (co-sc)

- 1978

-

Interiors (d, sc only)

- 1979

-

Manhattan (co-sc)

- 1980

-

Stardust Memories

- 1982

-

A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy

- 1983

-

Zelig

- 1984

-

Broadway Danny Rose

- 1985

-

The Purple Rose of Cairo (d, sc only)

- 1986

-

Hannah and Her Sisters

- 1987

-

Radio Days (role as narrator)

- 1988

-

September (d, sc only); Another Woman (d, sc only)

- 1989

-

Crimes and Misdemeanors ; "Oedipus Wrecks" episode in New York Stories

- 1990

-

Alice (d, sc only)

- 1992

-

Shadows and Fog ; Husbands and Wives

- 1993

-

Manhattan Murder Mystery

- 1994

-

Bullets over Broadway (d, co-sc only); Don't Drink the Water (for TV)

- 1995

-

Mighty Aphrodite

- 1996

-

Everyone Says I Love You

- 1997

-

Deconstructing Harry

- 1998

-

Celebrity

- 1999

-

Sweet and Lowdown

- 2000

-

Small Time Crooks

Other Films:

- 1965

-

What's New, Pussycat? (sc, role)

- 1966

-

What's up, Tiger Lily? (co-sc, assoc pr, role as host/narrator); Don't Drink the Water (play basis)

- 1967

-

Casino Royale (Huston and others) (role)

- 1972

-

Play It Again, Sam (Ross) (sc, role)

- 1976

-

The Front (Ritt) (role)

- 1987

-

King Lear (Godard) (role)

- 1991

-

Scenes from a Mall (Mazursky) (role)

- 1997

-

Liv Ullmann scener fra et liv (Hambro) (narrator); Cannesyles 400 coups (Nadeau—for TV) (as himself); Just Shoot Me (for TV) (role)

- 1998

-

Waiting for Woody (as himself); The Imposters (role); Antz Darnell, Guterman) (role); Wild Man Blues (Kopple) (as himself)

- 2000

-

Picking up the Pieces (Arau) (role); Company Man (Askin,McGrath) (role); Ljuset håller mig sällskap ( Light Keeps Me Company ) (Nykvist) (role)

Publications

By ALLEN: books—

Don't Drink the Water (play), 1967.

Play It Again, Sam (play), 1969.

Getting Even , New York, 1971.

Death: A Comedy in One Act and God: A Comedy in One Act (plays), 1975.

Without Feathers , New York, 1975.

Side Effects , New York, 1980.

The Floating Lightbulb (play), New York, 1982.

Four Films of Woody Allen ( Annie Hall , Interiors , Manhattan , Stardust Memories ), New York, 1982.

Hannah and Her Sisters , New York, 1987.

Three Films of Woody Allen ( Zelig , Broadway Danny Rose , The Purple Rose of Cairo ), New York, 1987.

The Complete Prose of Woody Allen (contains Getting Even, Without Feathers , and Side Effects ), New York, 1992.

The Illustrated Woody Allen Reader , edited by Linda Sunshine, New York, 1993.

Woody Allen on Woody Allen: In Conversation with Stig Bjorkman , London, 1994.

By ALLEN: articles—

"Woody Allen Interview," with Robert Mundy and Stephen Mamber, in Cinema (Beverly Hills), Winter 1972/73.

"The Art of Comedy: Woody Allen and Sleeper ," interview with J. Trotsky, in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), Summer 1974.

"A Conversation with the Real Woody Allen (or Someone Just like Him)," with K. Kelley, in Rolling Stone (New York), 1 July 1976.

"Woody Allen Is Feeling Better," interview with B. Drew, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), May 1977.

"Comedy Directors: Interviews with Woody Allen," with M. Karman, in Millimeter (New York), October 1977.

"Scenes from a Mind," interview with I. Halberstadt, in Take One (Montreal), November 1978.

"Vous avez dit Woody?," interview with Robert Benayoun, in Positif (Paris), May 1984.

"The Kobal Tapes: Woody Allen," interview with John Kobal, in Films and Filming (London), December 1985.

"Fears of a Clown," an interview with Tom Shales, and "Killing Joke," an interview with Roger Ebert, in Time Out (London), 1 November 1989.

Interview with Silvio Bizio, in Empire (London), August 1990.

"The Heart Wants What It Wants," an interview with Walter Isaacson, in Time , 31 August 1992.

"Unhappily Ever After," an interview with J. Adler and others, in Newsweek , 31 August 1992.

Interview with S. Bjorkman, in Cahiers du Cinema (Paris), vol. 87, 1992.

Interview with A. DeCurtis, in Rolling Stone , 16 September 1993.

"Rationality and the Fear of Death," in The Metaphysics of Death , edited by John Martin Fischer, 1993.

Interview with Studs Terkel, in Four Decades with Studs Terkel , audiocassette collection of interviews with various figures (recorded between 1955 and 1989), HighBridge Company, 1993.

"Woody Allen in Exile" (also cited as "'So, You're the Great Woody Allen?' A Man on the Street Asked Him"), an interview with Bill Zehme, in Esquire (New York), October 1994.

"Biting the Bullets," interview with Geoff Andrew, in Time Out (London), 5 April 1995.

"Play It Again, Man," interview with Linton Chiswick, in Time Out (London), 13 March 1996.

"Bullets over Broadway Danny Rose of Cairo: The Continuous Career of Woody Allen," an interview with Tomm Carroll, in DGA (Los Angeles), May-June 1996.

Interview with Olivier De Bruyn, in Positif (Paris), February 1999.

By ALLEN: television interviews—

Interview with Morley Safer, broadcast on the 60 Minutes television program, Columbia Broadcasting System, 13 December 1987.

Interview with Steve Croft, broadcast on the 60 Minutes television program, Columbia Broadcasting System, 22 November 1992.

Interview with Melvyn Bragg, broadcast on The South Bank Show , London, 16 January 1994.

"Woody!," an interview with Bob Costas, broadcast in two segments on the Dateline NBC television program, National Broadcasting Company, 29 and 30 November 1994.

On ALLEN: books—

Lax, Eric, On Being Funny: Woody Allen and Comedy , New York, 1975.

Yacowar, Maurice, Loser Take All: The Comic Art of Woody Allen , Oxford, 1979; expanded edition, 1991.

Jacobs, Diane, . . . But We Need the Eggs: The Magic of Woody Allen , New York, 1982.

Brode, Douglas, Woody Allen: His Films and Career , London, 1985.

Benayoun, Robert, Woody Allen: Beyond Words , London, 1987; as The Films of Woody Allen , New York, 1987.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto, The Films of Woody Allen , Florence, 1987.

de Navacelle, Thierry, Woody Allen on Location , London, 1987.

Pogel, Nancy, Woody Allen , Boston 1987.

Sinyard, Neil, The Films of Woody Allen , London, 1987.

Altman, Mark A., Woody Allen Encyclopedia: Almost Everything You Wanted to Know about the Woodster but Were Afraid to Ask , Pioneer Books, 1990.

McCann, Graham, Woody Allen: New Yorker , New York, 1990.

Hirsch, Foster, Love, Sex, Death, and the Meaning of Life: The Films of Woody Allen , revised and updated, Limelight, 1991.

Lax, Eric, Woody Allen: A Biography , London, 1991.

Weimann, Frank, Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Woody Allen , New York, 1991.

Wernblad, Annette, Brooklyn Is Not Expanding: Woody Allen's Comic Universe , Rutherford, New Jersey, 1992.

Carroll, Tim, Woody and His Women , London, 1993.

Girgus, Sam B., The Films of Woody Allen , Cambridge, 1993.

Groteke, Kristi, Woody and Mia: The Nanny's Tale , London, 1994.

Spignesi, Stephen, The Woody Allen Companion , London, 1994.

Blake, Richard A., Woody Allen: Profane and Sacred , Lanham, 1995.

Hamill, Brian, Woody Allen at Work: The Photographs of Brian Hamill , New York, 1995.

Lee, Sander H., Woody Allen's Angst: Philosophical Commentaries on His Serious Films , Jefferson, 1996.

Curry, Renee R., ed. Perspectives on Woody Allen , New York, 1996.

Fox, Julian, Woody: Movies from Manhattan , New York, 1997.

Nichols, Mary P., Reconstructing Woody: Art, Love, and Life in the Films of Woody Allen , Lanham, Maryland, 1998.

Baxter, John, Woody Allen: A Biography , New York, 1999.

Meade, Marion, The Unruly Life of Woody Allen: A Biography , Boston, 2000.

On ALLEN: articles—

"Woody, Woody Everywhere," in Time (New York), 14 April 1967.

"Woody Allen Issue," of Cinema (Beverly Hills), Winter 1972/73.

Wasserman, Harry, "Woody Allen: Stumbling through the Looking Glass," in Velvet Light Trap (Madison), Winter 1972/73.

Maltin, Leonard, "Take Woody Allen—Please!," in Film Comment (New York), March-April 1974.

Remond, A., " Annie Hall ," in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 15 December 1977.

Yacowar, Maurice, "Forms of Coherence in the Woody Allen Comedies," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), no. 2, 1979.

Canby, Vincent, "Film View: Notes on Woody Allen and American Comedy," in New York Times , 13 May 1979.

Dempsey, M., "The Autobiography of Woody Allen," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1979.

Teitelbaum, D., "Producing Woody: An Interview with Charles H. Joffe," in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), April/May 1980.

Combs, Richard, "Chameleon Days: Reflections on Non-Being," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), November 1983.

Lahr, John, in Automatic Vaudeville: Essays on Star Turns , New York, 1984.

Liebman, R.L., "Rabbis or Rakes, Schlemiels or Supermen? Jewish Identity in Charles Chaplin, Jerry Lewis and Woody Allen," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), July 1984.

Caryn James, "Auteur! Auteur! The Creative Mind of Woody Allen," in New York Times Magazine , 19 January 1986.

"Woody Allen Section," of Film Comment (New York), May-June 1986.

Combs, Richard, "A Trajectory Built for Two," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), July 1986.

Morris, Christopher, "Woody Allen's Comic Irony," in Literature/ Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 15, no. 3, 1987.

Yacowar, Maurice, "Beyond Parody: Woody Allen in the Eighties," in Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Winter 1987.

Dunne, Michael, " Stardust Memories, The Purple Rose of Cairo , and the Tradition of Metafiction," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), Fall 1987.

Preussner, Arnold W., "Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo and the Genres of Comedy," and Paul Salmon and Helen Bragg, "Woody Allen's Economy of Means: An Introduction to Hannah and Her Sisters ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 16, no. 1, 1988.

"Woody Allen," in Film Dope (London), March 1988.

Downing, Crystal, "Broadway Roses: Woody Allen's Romantic Inheritance," and Ronald D. LeBlanc, " Love and Death and Food: Woody Allen's Comic Use of Gastronomy," in Literature/ Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 17, no. 1, 1989.

Girlanda, E., and A. Tella, "Allen: Manhattan Transfer," in Castoto Cinema , July/August 1990.

Comuzio, E., " Alice ," in Cinema Forum , vol. 31, 1991.

Green, D., "The Comedian's Dilemma: Woody Allen's 'Serious' Comedy," in Literature/Film Quarterly , vol. 19, no. 2, 1991.

Tutt, R., "Truth, Beauty, and Travesty: Woody Allen's Well-wrought Run," in Literature/Film Quarterly , vol. 19, no. 2, 1991.

Welsh, J., "Allen Stewart Konigsberg Becomes Woody Allen: A Comic Transformation," in Literature/Film Quarterly , vol. 19, no. 2, 1991.

Quart, L., "Woody Allen's New York," in Cineaste , vol. 19, no. 2, 1992.

Mitchell, Sean, "The Clown Who Would Be Chekhov," in The Guardian (U.K.), 23 March 1992.

Rockwell, John, "Woody Allen: France's Monsieur Right," in New York Times , 5 April 1992.

Corliss, Richard, "Scenes from a Breakup," in Time , 31 August 1992.

Cagle, Jess, "Love and Fog," in Entertainment Weekly , 18 September 1992.

Hoban, Phoebe, "Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Woody and Mia but Were Afraid to Ask," in New York , 21 September 1992.

Johnstone, Iain, "Moving Pictures Drawn from Life," in The Sunday Times (London), 25 October 1992.

Romney, J. " Husbands and Wives ," in Sight and Sound (London), November 1992.

Perez-Pena, R., "Woody Allen Tells of Affair as Custody Battle Begins," in New York Times , 20 March 1993.

Marks, P., "Allen Loses to Farrow in Bitter Custody Battle," in New York Times , 8 June 1993.

Baumgarten, Murray, "Film and the Flattening of American Jewish Fiction: Bernard Malamud, Woody Allen, and Spike Lee in the City," in Contemporary Literature , Fall 1993.

Desser, David, "Woody Allen: The Schlemiel as Modern Philosopher," in American-Jewish Filmmakers: Traditions and Trends , University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Troncale, J. C., "Illusion and Reality in Woody Allen's Double Film of The Purple Rose of Cairo ," in Proceedings of the Conference on Film and American Culture , edited by Joel Schwartz, College of William and Mary, 1994.

Romney, Jonathan, "Shelter from the Storm," in Sight and Sound (London), February 1994.

Davis, Robert, "A Stand-up Guy Sits Down: Woody Allen's Prose," in Short Story , Fall 1994.

McGrath, Douglas, "If You Knew Woody like I Knew Woody," in New York , 17 October 1994.

Deleyto, Celestino, "The Narrator and the Narrative: The Evolution of Woody Allen's Films," in Film Criticism (Meadville), Winter 1994–1995.

Lahr, John, "The Imperfectionist," in New Yorker , 9 December 1996.

Romney, Jonathan, "Scuzzballs like Us," in Sight and Sound (London), April 1998.

On ALLEN: film—

Woody Allen: An American Comedy (Harold Mantell), 1978.

* * *

Woody Allen's roots in American popular culture are broad, laced with a variety of European literary and cinematic influences, some of them (Ingmar Bergman and Dostoevsky, for example) paid explicit homage within his films, others more subtly woven into the fabric of his work from a wide range of earlier comic traditions. Allen's genuinely original voice in the cinema recalls writer-directors like Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Preston Sturges, who dissect their portions of the American landscape primarily through comedy. In his creative virtuosity Allen also resembles Orson Welles, whose visual and verbal wit, though contained in seemingly non-comic genres, in fact exposes the American character to satirical scrutiny. Allen's landscape, though, is particular, being that of Manhattan, its generally middle-class inhabitants and their culture and neuroses, of which he is the cinema's great chronicler, much as Martin Scorsese is that of New York City's underbelly.

More often than not, Allen has appeared in his own films, resembling the great silent-screen clowns who created, then developed, an ongoing screen presence. However, Allen's film persona depends upon heard dialogue and especially thrives as an updated, urbanely hip, explicitly Jewish amalgam of personality traits and delivery methods associated with comic artists who reached their pinnacle in radio and film in the 1930s and 1940s. The key figures Allen plays in his own films puncture the dangerous absurdities of their universe and guard themselves against them by maintaining a cynical, even misogynistic, verbal offense in the manner of Groucho Marx and W. C. Fields, alternated with incessant displays of self-deprecation akin to the cowardly, unhandsome persona established by Bob Hope in, for example, his Road series.

Allen's early films emerge logically from the sharp, pointedly exaggerated jokes and sketches he first wrote for others, then later delivered himself as a stand-up comic in clubs and on television. As with the early films of Buster Keaton, most of Allen's early works depend on explicit parody of recognizable genres. Even the films of his pre- Annie Hall period, which do not formally rely upon a particular genre, incorporate references to various films and directors as commentary on the specific targets of social, political, or literary satire: political turbulence of the 1960s via television news coverage in Bananas ; the pursuit by intellectuals of large religious and philosophical questions via the methods of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in Love and Death ; American sexual repression via the self-discovery guarantees offered by sex manuals in Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex. All these issues reappear in Allen's later, increasingly mature work, repeatedly revealing the anomaly of comedy that is cerebral in nature, dependent even in its occasional sophomoric moments upon an educated audience that responds to his brand of self-reflexive, literary, political, and sexual humor. But Allen distrusts and satirizes formal education and institutionalized discourse which, in his films, lead repeatedly to humorless intellectual preening. "Those who can't do, teach, and those who can't teach, teach gym," declares Alvy Singer in Annie Hall. No character in that film is treated with greater disdain than the Columbia professor who smugly pontificates on Fellini while standing in line waiting to see The Sorrow and the Pity . Allen inflicts swift, cinematically appropriate justice. In Manhattan , Yale, a university professor of English, bears the brunt of Allen's moral condemnation as a self-rationalizing cheat who is far "too easy" on himself.

In Annie Hall , his Oscar-winning breakthrough film, Allen the writer (with Marshall Brickman) recapitulates and expands on his emerging topics but removes them from the highly exaggerated apparatus of his earlier parodies. Alvy Singer (Allen) and Annie Hall (Diane Keaton in her most important of several roles for Allen) enact an urban-neurotic variation on the mismatched lovers of screwball comedy, set against a realistic New York City mise-en-scène but slanted away from farce and toward character analysis.

Annie Hall makes indelible the Woody Allen onscreen persona—a figure somehow involved in show business or the arts and obsessive about women, his parents, his childhood, his values, his terror of illness and death; perpetually and hilariously taking the mental temperature of himself and everyone around him. Part whiner, part nebbish , part hypochondriac, this figure is also brilliantly astute and consciously funny, miraculously irresistible to women—for a while—particularly (as in Annie Hall and Manhattan ) when he can serve as their teacher. This developing figure in Allen's work is both comic victim and witty victimizer, a moral voice in an amoral age who repeatedly discovers that the only true gods in a godless universe are cultural and artistic—movies, music, art, architecture—a perception pleasurably reinforced visually and aurally throughout his best films. With rare exceptions— Hannah is a notable one—this figure at the film's fadeout appears destined to remain alone, enabling him, by implication, to continue functioning as a sardonically detached observer of human imperfection, including his own. In Annie Hall , this characterization, despite its suffusion in angst , remains purely comic but Allen becomes progressively darker—and harder on himself—as variants of this figure emerge in the later films.

Comedy, even comedy that aims for the laughter of recognition based on credibility of character and situation, rests heavily on exaggeration. In Zelig , the tallest of Woody Allen's cinematic tall tales, the central figure is a human chameleon who satisfies his overwhelming desire for conformity by physically transforming himself into the people he meets. Zelig's bizarre behavior is made visually believable by stunning shots that appear to place the character of Leonard Zelig (Allen) alongside famous historical figures within actual newsreel footage of the 1920s and 1930s.

Shot in Panavision and velvety black-and-white, and featuring a Gershwin score dominated by "Rhapsody in Blue," Manhattan reiterates key concerns of Annie Hall but enlarges the circle of participants in a sexual la ronde that increases Allen's ambivalence toward the moral terrain occupied by his characters—especially by Ike Davis (Allen), a forty-two-year-old man justifying a relationship with a seventeen-year-old girl (Mariel Hemingway). By film's end she has become an eighteen-year-old woman who has outgrown him, just as Annie Hall outgrew Alvy Singer. The film (like Hannah and Her Sisters later) is, above all, a celebration of New York City, which Ike, like Allen, "idolize[s] all out of proportion."

In the Pirandellian The Purple Rose of Cairo , the fourth Allen film to star Mia Farrow, a character in a black-and-white film-within-thefilm leaps literally out of the frame into the heroine's local movie theatre. Here film itself—in this case the movies of the 1930s—both distorts reality by setting dangerously high expectations, and makes it more bearable by permitting Cecilia, Allen's heroine, to escape from her dismal Depression existence. Like Manhattan before it, and Hannah and Her Sisters and Radio Days after it, The Purple Rose of Cairo examines the healing power of popular art.

Arguably Allen's finest film to date, Hannah and Her Sisters shifts his own figure further away from the center of the story than he had ever been before, treating himself as one of nine prominent characters in the action. Allen's screenplay weaves an ingenious tapestry around three sisters, their parents, assorted mates, lovers, and friends (including Allen as Hannah's ex-husband Mickey Sachs). A Chekhovian exploration of the upper-middle-class world of a group of New Yorkers a decade after Annie Hall , Hannah is deliberately episodic in structure, its sequences separated by Brechtian title cards that suggest the thematic elements of each succeeding segment. Yet it is an extraordinarily seamless film, unified by the family at its center; three Thanksgiving dinner scenes at key intervals; an exquisite color celebration of an idyllic New York City; and music by Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, and Puccini (among others) that italicizes the genuinely romantic nature of the film's tone. The most optimistic of Allen's major films, Hannah restores its inhabitants to a world of pure comedy, their futures epitomized by the fate of Mickey Sachs. For once, the Allen figure is a man who will live happily ever after, a man formerly sterile, now apparently fertile, as is comedy's magical way.

Arguably his most morally provocative and ambiguous film, Crimes and Misdemeanors further marginalizes—and significantly darkens—the figure Woody Allen invites audiences to confuse with his offscreen self. The self-reflexive plight of filmmaker Cliff Stern (Allen) alternates with the central dilemma confronted by ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), a medical pillar of society who bears primary, if indirect, responsibility for the murder of his mistress (Anjelica Huston). Religious and philosophical issues present in Allen's films since Love and Death achieve a new and serious resonance, particularly through the additional presence of a faith-retaining rabbi gradually (in one of numerous Oedipal references in Allen's work) losing his sight, and a Holocaust survivor-philosopher who preaches the gospel of endurance—then commits suicide by (as his note prosaically puts it) "going out the window." In its pessimism, diametrically opposed to the joyous Hannah and Her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors posits a universe utterly and disturbingly devoid of poetic justice or moral certainty. The picture's genuinely comic sequences, usually involving Cliff and Alan Alda as his fatuous producer brother-in-law ("Comedy is tragedy plus time!") do not contradict the fact that it is Allen's most somber major film, a comedy-melodrama that in its final sequence crosses the brink to the level of domestic tragedy. Here, the Allen figure is not only alone, as he has been in the past, but alone and in despair. In entirely contrasting visual ways, Alice and Shadows and Fog exhibit immediately recognizable Allen concerns in highly original fashion. A glossy, airy, gently satiric modern fairy tale, Alice implicitly functions as Allen's most open love letter to Mia Farrow. Her idealized title character searches for meaning in a yuppified New York City. Eventually, she finds it by leaving her husband, meeting Mother Theresa, and, especially, by discovering that her two children offer her the only genuine vehicle for romance in this romantic comedy manqué . The film's final shot displays a glowing Alice joyfully pushing them on playground swings as two former women friends, in voice-over dialogue, bemoan her self-selected maidless and nannyless condition, one which the film clearly intends us to embrace.

In Shadows and Fog , Allen employs a specific cinematic genre more directly than at any time since the 1970s. His homage to German Expressionism, Shadows and Fog is shot in black and white in a manner deliberately reminiscent of the films of Pabst, Lang, and Murnau. That visual style and the placement at the film's center of a distinctly Kafkaesque hero (played by Allen) combine to make Shadows and Fog Allen's most overtly "European" and wryly metaphysical film since Interiors fourteen years earlier. Not surprisingly, Shadows and Fog was greeted by critics much more favorably in Europe than in the United States, but left audiences on both continents less than satisfied.

As Chekhov's forgiving spirit energizes the comic tone of Hannah and Her Sisters , so the playwright August Strindberg's hostility controls the dark marital terrain of Husbands and Wives. Strindbergian gender battles frequently appear in earlier Allen films, but they are more typically rescued back from the precipice by comedy. Allen's partial attempt to attribute comic closure to Husbands and Wives pleases but inadequately convinces. While the film (which might have been more accurately titled Husbands, Wives, and Lovers ) is often extremely funny, its portrait of two deteriorating marriages is as corrosive as anything in the Allen canon. Husbands and Wives contains other elements long present in Allen's films: multiple story-lines, a deliberately episodic structure covering a period of about a year, and the involvement of a central character, Gabe Roth (played by Allen), with a woman (Juliette Lewis) young enough to be his daughter. Unlike Ike Davis's relationship with Tracy in Manhattan , however, this one is consummated—and concluded—with only a kiss.

Despite the presence of familiar material, Husbands and Wives shows Allen continuing to break new ground, particularly in the film's technical virtuosity. The frequent use of a hand-held camera reinforces the neurotic, darting, unpredictable behavior of key characters. Moving beyond his use of title cards to provide Brechtian distancing in Hannah and Her Sisters , Allen here employs a documentary technique to punctuate the main action of the film. The central characters and a minor one (the ex-husband of Judy Roth, the woman played by Mia Farrow) are individually interviewed by an off-screen male voice, which appears to function simultaneously as documentary recorder of their woeful tales and as therapist to their psyches. These sequences are inserted periodically throughout the film, as the interviewees speak directly to the camera—and therefore to us , thus forcing the audience to participate in the filmmakerinterviewer's role as therapist.

Husbands and Wives deserves a place alongside Hannah and Her Sisters and Crimes and Misdemeanors as representing Allen's most textured and mature work to date. But the film's visual and thematic pleasures have been obscured by audience desire to see in Husbands and Wives the spectacle of art imitating life with a vengeance; and, in fact, Husbands and Wives does contain uncanny links to the Allen-Farrow breakup even though the film was completed before their relationship came to a dramatic and controversial end, attended by a blaze of publicity that further alienated those audiences not addicted to Allen and narrowed his already selective audience base in the United States.

The type of ethical dilemma which occupies such a central place in the Allen canon (and which usually finds its most articulate definition in the mouths of characters played by Allen himself) appeared to have tumbled out of an Allen movie and onto worldwide front pages. ("Life doesn't imitate art; it imitates bad television," says Allen's Gabe Roth in Husbands and Wives. ) In 1992, shortly before the release of Husbands and Wives , Allen's romantic relationship with Soon-Yi Previn, Mia Farrow's twenty-one-year-old adopted daughter, was discovered by her mother, who made the fact public. Furious and ugly charges and countercharges ensued, resulting in Allen's loss of custody of his three children a year later, while the legal wrangling continued unabated for some considerable time. It is not too fanciful to suggest that Allen's personal crisis accounted for what, on the one hand, has appeared to be a search for new directions—imaginative, even experimental—and on the other hand, a loss of focus and a diminished coherency of goal and vision.

Nonetheless, in the eight-year period following the release of Husbands and Wives , Allen, undaunted by personal tragedy and adverse publicity, continued to work steadily, but the collected films of this period are less easy to pigeon-hole or analyze and have mostly been something of a disappointment to fans and a puzzlement to several critics. He reverted firmly to his distinctive comic universe with Don't Drink the Water , adapted from his early Broadway play and first shown in America on network television; Manhattan Murder Mystery , a comedy-mystery in the manner of The Thin Man films and the Mr. and Mrs. North radio and television series, with Diane Keaton (replacing Mia Farrow, who was originally scheduled to play Allen's wife) and Alan Alda; the breathtakingly cruel and brilliantly funny Bullets over Broadway, set in the 1920s/1930s and satirizing the marriage of theater and the underworld that was a staple of so many late 1920s and early 1930s films. At the center is a playwright (John Cusack) grappling with his first Broadway production and becoming involved with a flamboyantly fey actress (Dianne Wiest). The character could be considered as an emblem for a younger Allen, but the film as a whole is richly comical and sad in its behind-the-scenes portrait of Broadway life and work, as well as awesome in its sense of period and its gentle parody of theatrical and underworld stereotypes. Mighty Aphrodite again tempts audiences to see elements of Allen's life reflected in the central plot issue of child adoption, but, with its parodies of Greek tragedy and its broadly satiric array of characters, the film rarely strays from its identification as genuine Allen comedy. These 1990s films reveal yet again why so many actors want to work with Allen: Dianne Wiest won her second supporting actress Oscar for her role in an Allen film for Bullets over Broadway (her first was for Hannah ); and Mira Sorvino won the same award for Mighty Aphrodite the following year.

But, while Allen's primary response to the tarnish on his personal reputation has been to keep making films, it might be suggested that he now needs to pause for thought and regain some perspective as to the motive force behind them. The four since Mighty Aphrodite have evidenced the lack of sure-footedness referred to above. His evident desire to spot and utilize talented actors, known and unknown, coincides with a rash of screenplays so heavily peopled as to blur the central characters, leaving audiences with far less to engage with than hitherto. The least successful, and perhaps most seriously troubled internally, of the last four of the 1990s is Deconstructing Harry , relentlessly and unattractively self-referential, and looking for its humor in fantasy and fantastical situations which have a certain farcical crudity in contrast to Allen's usually penetrating verbal wit. Celebrity , miscasting Kenneth Branagh in the central role that Allen would once have played, is not without its pleasures, but fails to cohere; Sweet and Lowdown , visiting the territory of Allen's other great love—jazz—is ambitious, entertaining, and boasts a wonderful performance from Sean Penn. If it is neither quite interesting nor quite funny enough, it is nonetheless endlessly inventive, and as good a jazz film as any in evoking the ethos of its subject. Arguably the clearest success of the four, its virtues criminally misunderstood by all but the cognoscenti , is Everyone Says I Love You , in which a now wispily aging Woody co-stars himself with the ravishing Julia Roberts, pushing the boundaries of his earlier collected oeuvre that invited us to accept his seemingly unlikely appeal for women, and almost self-parodying the nebbish aspects of his screen persona. The film, unusually, broadens Allen's physical landscape, setting the core of the Allen-Roberts romance in Venice (a city that features significantly in Barbara Kopple's documentary following Woody and his band—and his wife Soon-Yi—on a European tour) and climaxing in Paris. Too long, structurally undisciplined, and a bit of a rag-bag it may be, but Everyone Says I Love You is a blissful homage to the Hollywood musical, knowing and affectionate.

Allen has always denied that his film persona is related to his own, although it is often justifiably difficult for us to believe that. "Is it over? Can I go now?" asks Gabe Roth of the off-screen interviewer in the final shot of Husbands and Wives. Divorced from his wife, Gabe is now alone, but he chooses to be. Gabe may not be happy—rarely is any character played by Woody Allen ever actually happy —but, unlike Clifford Stern at the end of Crimes and Misdemeanors , Gabe is decidedly not in despair. Neither, hopefully, is Woody Allen. It is clear that the fertile imagination, while perhaps floundering to find a new form, is intact, and the comic spirit still present. To the question "Whither now?" must come the answer "Who knows?" But whatever path he treads in the future, Woody Allen has proved one of the few auteurs of the American cinema worthy of the over-used term, and it may well be that his great masterwork is yet to spring from the autumn of his years.

—Mark W. Estrin, updated by Robyn Karney

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: