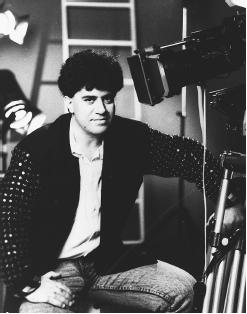

Pedro AlmodÓvar - Director

Nationality: Spanish. Born: Calzada de Clatrava, La Mancha, Spain, 1951 (some sources say 1947). Career: Moved to Madrid and worked for National Telephone Company, 1967; wrote comic strips and articles for underground magazines; joined independent theatre group Los Goliardos and started making Super-8 films with them, 1974; first feature, Pepi , released 1980; also a rock musician, has written music for his own films. Awards: Glauber Rocha Award for Best Director, Rio Film Festival, and Los Angeles Film Critics Association "New Generation" Award, 1987, for Law of Desire; National Society of Film Critics Award, special citation for originality, 1988; Venice International Film Festival best screenplay award, National Board of Review of Motion Pictures best foreign film, New York Film Critics Circle best foreign film, and Felix Award for best young film, all 1988, and Academy Award nomination for best foreign film, Orson Welles Award for best foreign-language film, both 1989, all for Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. Agent: El Deseo SA, 117 Velázquez, Madrid, Spain.

Films as Director:

- 1974

-

Dos putas, o, Historia de amor que termina en boda ( Two Whores, or, A Love Story that Ends in Marriage ) (Super-8); La caida de Sodoma ( The Fall of Sodom ) (Super-8)

- 1975

-

Homenaje ( Homage ) (Super-8)

- 1976

-

La estrella ( The Stars ) (Super-8)

- 1977

-

Sexo va: Sexo vienne ( Sex Comes and Goes ) (Super-8); Complementos (shorts)

- 1978

-

Folle, folle, folleme, Tim ( Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Tim )(Super-8, full-length); Salome (16mm)

- 1980

-

Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas de montón ( Pepi, Luci, Bom and Lots of Other Girls ) (+ sc)

- 1982

-

Laberinto de pasiones ( Labyrinth of Passions ) (+ sc, + pr, role)

- 1983

-

Entre tinieblas ( Into the Dark ; The Sisters of Darkness )(+ sc, song)

- 1984

-

Qué me hecho yo para merecer esto? ( What Have I Done to Deserve This? ) (+ sc)

- 1986

-

Matador (+ sc); La ley del deseo ( Law of Desire ) (+ sc, score, song)

- 1988

-

Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios ( Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown ) (+ sc, + pr)

- 1990

-

Atame! ( Tie Me up, Tie Me Down! ) (+ sc)

- 1991

-

Tacomes lejanos ( High Heels ) (+ sc, song)

- 1993

-

Kika (+ sc)

- 1995

-

Le flor de mi secreto ( The Flower of My Secret ) (+ sc)

- 1997

-

Carne trémula ( Live Flesh ) (+ sc, role as himself)

- 1999

-

Todo sobre mi madre ( All about My Mother ) (+ sc)

Films as Producer:

- 1993

-

Acción mutante ( Mutant Action )

- 1996

-

Mi nombre es sombra (assoc pr)

Publications

By ALMODÓVAR: books—

El sueno de la razon (short stories), Madrid, 1980.

Fuego en las entranas ( Fire Deep Inside ) (novel), Madrid, 1982.

Patty Diphusa y otros textos ( Patty Diphusa and Other Writings ), Barcelona, 1991.

Almodóvar on Almodóvar , London, 1995.

The Flower of My Secret , London, 1997.

By ALMODÓVAR: articles—

Interview in Contracampo (Madrid), September 1981.

Interview with J. C. Rentero, in Casablanca (Madrid), May 1984.

"Pleasure and the New Spanish Mentality," an interview with Marsha Kinder, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1987.

Interview in Time Out (London), 2 November 1988.

Interview in Film Comment (New York), November/December 1988.

Interview in Films and Filming (London), June 1989.

Interview in Inter/View (New York), January 1990.

Interview in City Limits (London), 5 July 1990.

Interview with J. Schnabel, in Interview (New York), January 1992.

"Perche il melodrama," an interview with E. Imparato, in Cineforum (Bergamo, Italy), April 1992.

Interview with F. Strauss, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1992.

Regular column (as "Patty Diphusa") in La Luna (Madrid).

Interview in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1997.

"The Pain in Spain," in Time Out (London), 10 May 1995.

Interview with Peter Paphides, in Time Out (London), 28 June 1995.

On ALMODÓVAR: books—

Bouza Vidal, Nuria, El cine de Pedro Almodóvar ( The Films of Pedro Almodóvar ), Madrid, 1988.

Boquerini, Pedro Almodóvar , Madrid, 1989.

Smith, Paul Julian, Desire Unlimited: The Cinema of Pedro Almodóvar , London, 1994.

Vernon, Kathleen M., and Barbara Morris, Post-Franco, Postmodern: The Films of Pedro Almodóvar , Westport, Connecticut, 1995.

On ALMODÓVAR: articles—

Sanchez Valdès, J., "Pedro Almodóvar: Laberinto de pasiones ," in Casablanca (Madrid), April 1982.

Paranagua, P. A., "Pedro Almodóvar. En deuxième vitesse," in Positif (Paris), June 1986.

Fernandez, Enrique, "The Lawyer of Desire," in Village Voice (New York), 7 April 1987.

Film Quarterly (Los Angeles), Fall 1987.

Kael, Pauline, "Red on Red," in New Yorker , 16 May 1988.

"Spain's Pedro Almodóvar on the Verge of Global Fame," in Variety (New York), 24 August 1988.

Kael, Pauline, "Unreal," in New Yorker , 14 November 1988.

Filmbiography, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), January 1989.

Films in Review (New York), January 1989.

Corliss, Richard, "Almodóvar à la Mode," in Time (New York), 30 January 1989.

Arroyo, J., "Pedro Almodóvar: Law and Desire," in Descant , vol. 20, no. 1–2, 1989.

Cadalso, I., "Pedro Almodóvar: A Spanish Perspective," in Cineaste , vol. 18, no. 1, 1990.

O'Toole, L., "Almodóvar in Bondage," in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 59, no. 4, 1990.

Bennett, Annie, "Tour de Farce," in 20/20 (London), January 1990.

"Pedro Almodóvar," in National Film Theatre Booklet (London), July 1990.

Kinder, M., " High Heels ," in Film Quarterly , vol. 45, no. 3, 1992.

Levy, S., "King of Spain," in American Film , January/February 1992.

Moore, L., "New Role for Almodóvar," in Variety (New York), 28 September 1992.

Strauss, F., "The Almodóvar Picture Show," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1993.

Williams, Bruce, "Slippery When Wet: En-sexualized Transgression in the Films of Pedro Almodóvar," in Post Script (Commerce), Summer 1995.

Smith, P.J., "Almodóvar and the Tin Can," in Sight and Sound (London), February 1996.

Toubiana, S., "Masculin, feminin," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1997.

* * *

Pedro Almodóvar is more than the most successful Spanish film export since Carlos Saura. At home, the production of Almodóvar's films, their premiers, and the works themselves are surrounded by scandal, and the Spanish popular press examines what the director eats, the qualities he looks for in a lover, and his weight fluctuations in a fashion normally reserved for movie stars and European royalty. Abroad, the films have surprised those with set notions of what Spanish camera is or should be; Almodóvar's uncompromising incorporation of elements specific to a gay culture into mainstream forms with wide crossover appeal has been held up as a model for other gay directors to emulate. The films and Almodóvar's creation of a carefully cultivated persona in the press have meshed into "Almodóvar," a singular trademark. "Almodóvar" makes the man and the movies interchangeable even as it overshadows both. The term now embodies, and waves the flag for, the "New Spain" as it would like to see itself: democratic, permissive, prosperous, international, irreverent, and totally different from what it was in the Franco years.

Almodóvar's career can be usefully divided into three stages: a marginal underground period in the 1970s, during which he personally funded and controlled every aspect of the shoestring-budgeted, generally short films, and which culminated in Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas de montón , his feature film debut; the early to mid-1980s, during which he was still writing and directing his increasingly costly though still low-budget films, but for other producers and with varying degrees of state subsidization; and, from The Law of Desire in 1986, a period in which he reverted to producing his own films, which now benefitted from substantial budgets (by Spanish standards), top technicians, and maximum state subsidies. Though critical reaction to his work has varied, each of his films has enjoyed increasing financial success until Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown , which became 1989's highest-grossing foreign film in North America and the most successful Spanish film ever in Spain.

Almodóvar's oeuvre makes a good argument for the auteur theory. One can trace to his first films themes and strategies that he would explore in different forms, with varying degrees of success but with increasing technical expertise, throughout the rest of his career. Almodóvar's films posit the absolute autonomy of the individual. From Pepi to Tie Me up! Tie Me Down! the central characters in his films (mostly women) either act as if there are no social restrictions, or are conscious of the price of transgression but willing to pay it if such actions lead to, or contain, pleasure.

In Almodóvar's films, the various paths to pleasure lead to a destination and fulfillment ( Matador ), a dead end and disappointment ( Dark Hideout, Women on the Verge ), or an endlessly winding path and continuous displacement ( The Law of Desire ), but never resignation. To explore these varied roads Almodóvar has over the years accumulated a rep company of actors (including Antonio Banderas, who graduated to Hollywoood stardom). When in an Almodóvar film, no matter how absurd the situation their characters might find themselves in, all the actors are directed to a style that relies on understatement and has often been called "naturalist" or "realist." For example, when in The Law of Desire Tina tells her brother that "she" had previously been a "he" and had run off to Morocco to have a love affair with their father, Carmen Maura acts it in a style considerably subtler than that used by, for example, June Allyson to tell us she really shouldn't have broken that date with Peter Lawford. This style of acting is partly what enables Almodóvar's often outrageous characters to be so emotionally compelling.

Almodóvar borrows indiscriminately from film history. A case in point is What Have I Done to Deserve This? which contains direct reference to, or echoes of, neo-realism, the caper film, Carrie , Buñuel, Wilder, Warhol, and Waters. Moreover, by his second period, beginning with Dark Hideout , it became clear that Almodóvar's preferred mode of cinema was the melodramatic. It is a mode that cuts across genre, equally capable of conveying the tragic and the comic, eminently emotional, adept at arousing intense audience identification, and capable of communicating complex psychological processes no matter what the character's gender or sexual orientation.

Almodóvar's signature, and a unique contribution to the movies, is the synthesis of the melodramatic mode with a clash of quotations. This combination allows Almodóvar both a quasi-classical Hollywood narrative structure (which facilitates audience identification) and a very self-conscious narration (which normally produces an alienation effect). This results in dialectical moments in which the absurd can be imbued with emotional resonance (the mother selling her son to the dentist in What Have I Done ); the emotional can be checked with cheek without disrupting identification (superimposing a character's crying eyes with the wheels of a car in The Law ); and camp can be imbued with depth without losing its wit (the transference of emotions that occurs when we see Pepa dubbing Joan Crawford's dialogue from Johnny Guitar in Women on the Verge ). At his best ( What Have I Done to Deserve This? , The Law of Desire, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown ), Almodóvar drills a heart into the postmodern and fills it with an operatic range of feeling.

Although Almodóvar's movies have garnered increasingly heady praise in the 1990s, one senses the critical establishment is consciously trying to legitimize him in their eyes. Why is it that when a comedy expert grows more "serious," he is, perforce, taken more seriously? Fortunately, Almodóvar's mature works remain vibrant, unpretentious melodramas (unlike Woody Allen, whose art films seem like Xerox copies of the masters he slavishly imitates). Although Almodóvar has been chastised for trying to have his soap opera and send it up, too, he accomplished just that impossibility with earlier works like Law of Desire. As arrestingly sentimental as All about My Mother is, and as disturbingly mournful as Live Flesh is, they lack the kick of less-acclaimed works like High Heels, an unabashed glimpse into the soul of Lana Turner. Whereas Almodóvar once passionately embraced the Hollywoodness of Douglas Sirk's women pictures, his most recent movies merely buss those stylized conventions on the cheek. Why is there such a frenzy to commend the new-improved maverick, simply because he now uses humor only as a diversionary tactic, instead of an integral part of his canon? Despite reservations about the shift in his approach, one admires Almodóvar's unabated insight into role-playing, his debunking of machismo, his celebration of tackiness, and his unsurpassed skill with actresses. If something joyful seems missing from latter-day Almodóvar, something has also been gained in his collaboration with actress Marisa Paredes, a gravely beautiful dynamo, whom the director uses to suggest the melancholy behind emotional extravagance. If films like The Flower of My Secret are high-wire acts between pathos and humor, then Paredes helps him keep his balance. Even if one reminisces about Almodóvar's teamwork with efervescent comediennes like Carmen Maura and Victoria Abril, one is relieved that he hasn't become the Spanish John Waters, a filmmaker whose rebelliousness now seems quaint. Exploring his gay sensibility, Almodóvar appeals to straight audiences, who share his appetite for the resurrection and re-invigoration of old movie cliches. In overlooked works like Kika , characters literally die for love, and this slick director understands that classic escapism has undying appeal for a reason. The genius of Almodóvar lies in succumbing to the absurdity of Hollywood romanticism, while recognizing it as an impossible ideal. After enduring bloodless Oscar-winners and critically correct masterpieces, the audience rushes to Almodóvar's movies because they act like a tonic.

—José Arroyo, updated by Robert J. Pardi

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: