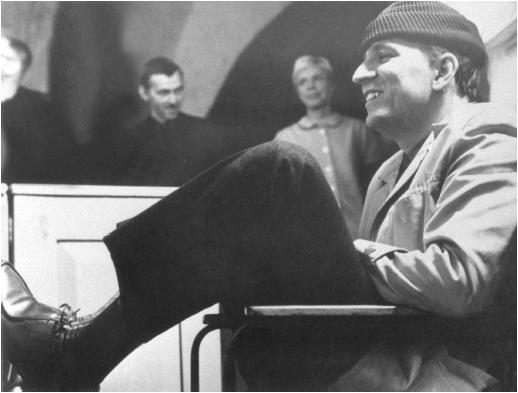

Ingmar Bergman - Director

Nationality: Swedish. Born: Ernst Ingmar Bergman in Uppsala, Sweden, 14 July 1918. Education: Palmgrens School, Stockholm, and Stockholm University, 1938–40. Family: Married 1) Else Fisher, 1943 (divorced 1945), one daughter; 2) Ellen Lundström, 1945 (divorced 1950), two sons, two daughters; 3) Gun Grut, 1951, one son; 4) Käbi Laretei, 1959 (separated 1965), one son; 5) Ingrid von Rosen, 1971 (died 1995). Also one daughter by actress Liv Ullmann. Career: Joined Svensk Filmindustri as scriptwriter, 1943; director of Helsingborg City Theatre, 1944; directed first film, Kris , 1946; began association with producer Lorens Marmstedt, and with Gothenburg Civic Theatre, 1946; began association with cinematographer Gunnar Fischer, 1948; director, Municipal Theatre, Malmo, 1952–58; began associations with Bibi Andersson and Max von Sydow, 1955; began association with cinematographer Sven Nykvist, 1959; became artistic advisor at Svensk Filmindustri, 1961; head of Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm, 1963–66; settled on island of Faro, 1966; established Cinematograph production company, 1968; moved to Munich, following arrest on alleged tax offences and subsequent breakdown, 1976; formed Personafilm production company, 1977; director at Munich Residenzteater, 1977–82; returned to Sweden, 1978; announced retirement from filmmaking, following Fanny and Alexander , 1982; directed These Blessed Two for Swedish television, 1985; concentrated on directing for the theater, 1985; Film Society of Lincoln Center presented a retrospective of almost all of Bergman's films as director, 1995; Brooklyn Academy of Music honored Bergman with a four-month-long Bergman Festival, 1995; The Museum of Television & Radio honored Bergman with a retrospective titled "Ingmar Bergman In Close-Up: The Television Work," 1995. Awards: Golden Bear, Berlin Festival, for Wild Strawberries , 1958; Gold Plaque, Swedish Film Academy, 1958; Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film, The Virgin Spring (1961), Through a Glass Darkly (1962), and Fanny and Alexander (1983); Oscar nominations, Best Director, for Cries and Whispers (1973), Face to Face (1976), and Fanny and Alexander (1983); Oscar nominations, Best Screenplay, for Wild Strawberries (1958), Through a Glass Darkly (1962), Cries and Whispers (1973), Face to Face (1976), and Fanny and Alexander (1983); co-winner of International Critics Prize, Venice Film Festival, for Fanny and Alexander ; Erasmus Prize (shared with Charles Chaplin), Netherlands, 1965; Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, 1970; Order of the Yugoslav Flag, 1971; Luigi Pirandello International Theatre Prize, 1971; honorary doctorate of philosophy, Stockholm University, 1975; Gold Medal of Swedish Academy, 1977; European Film Award, 1988; Le Prix Sonning, 1989; Praemium Imperiale Prize, 1991.

Films as Director:

- 1946

-

Kris ( Crisis ) (+ sc); Det regnar på vår kärlek ( It Rains on Our Love ; The Man with an Umbrella ) (+ co-sc)

- 1947

-

Skepp till Indialand ( A Ship Bound for India ; The Land of Desire ) (+ sc)

- 1948

-

Musik i mörker ( Music in Darkness ; Night Is My Future ); Hamnstad ( Port of Call ) (+ co-sc)

- 1949

-

Fängelse ( Prison ; The Devil's Wanton ) (+ sc); Törst ( Thirst ; Three Strange Loves )

- 1950

-

Till glädje ( To Joy ) (+ sc); Sånt händer inte här ( High Tension ; This Doesn't Happen Here )

- 1951

-

Sommarlek ( Summer Interlude ; Illicit Interlude ) (+ co-sc)

- 1952

-

Kvinnors väntan ( Secrets of Women ; Waiting Women ) (+ sc)

- 1953

-

Sommaren med Monika ( Monika ; Summer with Monika ) (+ co-sc); Gycklarnas afton ( The Naked Night ; Sawdust and Tinsel ) (+ sc)

- 1954

-

En lektion i kärlek ( A Lesson in Love ) (+ sc)

- 1955

-

Kvinnodröm ( Dreams ; Journey into Autumn ) (+ sc); Sommarnattens leende ( Smiles of a Summer Night ) (+ sc)

- 1957

-

Det sjunde inseglet ( The Seventh Seal ) (+ sc); Smultronstället ( Wild Strawberries ) (+ sc)

- 1958

-

Nära livet ( Brink of Life ; So Close to Life ) (+ co-sc); Ansiktet ( The Magician ; The Face ) (+ sc)

- 1960

-

Jungfrukällen ( The Virgin Spring ); Djävulens öga ( The Devil's Eye ) (+ sc)

- 1961

-

Såsom i en spegel ( Through a Glass Darkly ) (+ sc)

- 1963

-

Nattvardsgästerna ( Winter Light ) (+ sc); Tystnaden ( The Silence ) (+ sc)

- 1964

-

För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor ( All These Women ; Now about These Women ) (+ co-sc under pseudonym "Buntel Eriksson")

- 1966

-

Persona (+ sc)

- 1967

-

"Daniel" episode of Stimulantia (+ sc, ph)

- 1968

-

Vargtimmen ( Hour of the Wolf ) (+ sc); Skammen ( Shame ; The Shame ) (+ sc)

- 1969

-

Riten ( The Ritual ; The Rite ) (+ sc); En passion ( The Passion of Anna ; A Passion ) (+ sc); Fårö-dokument ( The Fårö Document ) (+ sc)

- 1971

-

Beröringen ( The Touch ) (+ sc)

- 1973

-

Viskningar och rop ( Cries and Whispers ) (+ sc); Scener ur ett äktenskap ( Scenes from a Marriage ) (+ sc, + narration, voice of the photographer) in six episodes: "Oskuld och panik (Innocence and Panic)"; "Kunsten att sopa unter mattan (The Art of Papering over Cracks)"; "Paula"; "Tåredalen (The Vale of Tears)"; "Analfabeterna (The Illiterates)"; "Mitt i natten i ett mörkt hus någonstans i världen (In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World)" (shown theatrically in shortened version of 168 minutes)

- 1977

-

Das Schlangenei ( The Serpent's Egg ; Ormens ägg ) (+ sc)

- 1978

-

Herbstsonate ( Autumn Sonata ; Höstsonaten ) (+ sc)

- 1979

-

Fårö-dokument 1979 ( Fårö 1979 ) (+ sc, narration)

- 1980

-

Aus dem Leben der Marionetten ( From the Life of the Marionettes ) (+ sc)

- 1982

-

Fanny och Alexander ( Fanny and Alexander ) (+ sc)

- 1983

-

Efter Repetitioner ( After the Rehearsal ) (+ sc)

- 1985

-

Karin's Face (short)

- 1991

-

Den Goda viljan ( The Best Intentions ) (mini for TV)

- 1992

-

Markisinnan de Sade (for TV) (+sc)

- 1995

-

Sista skriket ( The Last Gasp ) (for TV) (+sc)

- 1997

-

Larmar och gör sig till ( In the Presence of a Clown ) (for TV) (+sc, ro as Mental Patient); Bergmans röst ( The Voice of Bergman (Bergdahl) (doc)

Other Films:

- 1944

-

Hets ( Torment ; Frenzy ) (Sjöberg) (sc)

- 1947

-

Kvinna utan ansikte ( Woman without a Face ) (Molander) (sc)

- 1948

-

Eva (Molander) (co-sc)

- 1950

-

Medan staden sover ( While the City Sleeps ) (Kjellgren) (synopsis)

- 1951

-

Frånskild ( Divorced ) (Molander) (sc)

- 1956

-

Sista paret ut ( Last Couple Out ) (Sjöberg) (sc)

- 1961

-

Lustgården ( The Pleasure Garden ) (Kjellin) (co-sc under pseudonym "Buntel Eriksson")

- 1974

-

Kallelsen ( The Vocation ) (Nykvist) (pr)

- 1975

-

Trollflöjten ( The Magic Flute ) (for TV) (+ sc)

- 1976

-

Ansikte mot ansikte ( Face to Face ) (+ co-pr, sc) (for TV, originally broadcast in serial form); Paradistorg ( Summer Paradise ) (Lindblom) (pr)

- 1977

-

A Look at Liv (Kaplan) (role as interviewee)

- 1986

-

Dokument: Fanny och Alexander (Carlsson) (subject)

- 1992

-

Den Goda Viljan ( The Best Intentions ) (sc); Sondagsbarn ( Sunday's Children ) (sc)

- 1996

-

Enskilda samtal ( Private Confessions ) (series for TV) (sc)

- 2000

-

Trolösa ( Faithless ) (sc)

Publications

By BERGMAN: books—

Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1960.

The Virgin Spring , New York, 1960.

A Film Trilogy (Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light , and The Silence) , New York, 1967.

Persona and Shame , New York, 1972.

Bergman on Bergman , edited by Stig Björkman and others, New York, 1973.

Scenes from a Marriage , New York, 1974.

Face to Face , New York, 1976.

Four Stories by Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1977.

The Serpent's Egg , New York, 1978.

Autumn Sonata , New York, 1979.

From the Life of the Marionettes , New York, 1980.

Fanny and Alexander , New York, 1982; London, 1989.

Talking with Ingmar Bergman , edited by G. William Jones, Dallas, Texas, 1983.

The Marriage Scenarios: Scenes from a Marriage; Face to Face; Autumn Sonata , New York, 1983.

The Seventh Seal , New York, 1984.

Laterna Magica , Stockholm, 1987; as The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography , London, 1988.

Bilder , Stockholm, 1988; published as Images: My Life in Film , New York, 1993.

Den goda viljan , Stockholm, 1991; published as The Best Intentions , New York, 1993.

Sondagsbarn , Stockholm, 1993; published as Sunday's Children , New York, 1994.

Ingmar Bergman: An Artist's Journey on Stage, Screen, in Print , edited by Roger W. Oliver, Arcade Publishers, 1995.

Private Confessions: A Novel , translated by Joan Tate, Arcade Publishers, 1997.

By BERGMAN: articles—

"Self-Analysis of a Film-Maker," in Films and Filming (London), September 1956.

"Dreams and Shadows," in Films and Filming (London), October 1956.

Interview with Jean Béranger, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), October 1958.

"Each Film Is My Last," in Films and Filming (London), July 1959.

"Bergman on Victor Sjöstrom," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1960.

"The Snakeskin," in Sight and Sound (London), August 1965.

"Schizophrenic Interview with a Nervous Film Director," by 'Ernest Riffe' (pseudonym), in Film in Sweden (Stockholm), no. 3, 1968, and in Take One (Montreal), January/February 1969.

"Moment of Agony," interview with Lars-Olof Löthwall, in Films and Filming (London), February 1969.

"Conversations avec Ingmar Bergman," with Jan Aghed, in Positif (Paris), November 1970.

Interview with William Wolf, in New York , 27 October 1980.

"The Making of Fanny and Alexander ," interview in Films and Filming (London), February 1983.

Interview with Peter Cowie, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), April 1983.

"Goodbye to All That: Ingmar Bergman's Farewell to Film," an interview with F. van der Linden and B.J. Bertina, in Cinema Canada (Montreal), February 1984.

"Kak suzdavalas," Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 30, no. 2/3, 1988.

Interview with S. Bjorkman and O. Assayas, in Cahiers du Cinema (Paris), October 1990.

Interview with Jan Aghed and Jannike Åhlund, in Positif (Paris), May 1998.

On BERGMAN: books—

Béranger, Jean, Ingmar Bergman et ses films , Paris, 1959.

Donner, Jörn, The Personal Vision of Ingmar Bergman , Bloomington, Indiana, 1964.

Maisetti, Massimo, La Crisi spiritulai dell'uomo moderno nei film di Ingmar Bergman , Varese, 1964.

Nelson, David, Ingmar Bergman: The Search for God , Boston, 1964.

Steene, Birgitta, Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1968.

Gibson, Arthur, The Silence of God: Creative Response to the Films of Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1969.

Wood, Robin, Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1969.

Sjögren, Henrik, Regi: Ingmar Bergman , Stockholm, 1970.

Young, Vernon, Cinema Borealis: Ingmar Bergman and the Swedish Ethos , New York, 1971.

Simon, John, Ingmar Bergman Directs , New York, 1972.

Kaminsky, Stuart, editor, Ingmar Bergman: Essays in Criticism , New York, 1975.

Bergom-Larsson, Maria, Ingmar Bergman and Society , San Diego, 1978.

Kawin, Bruce, Mindscreen: Bergman, Godard, and the First-Person Film , Princeton, 1978.

Sjöman, Vilgot, L. 136. Diary with Ingmar Bergman , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1978.

Manvell, Roger, Ingmar Bergman: An Appreciation , New York, 1980.

Mosley, Philip, Ingmar Bergman: The Cinema as Mistress , Boston, 1981.

Petric, Vlada, editor, Film and Dreams: An Approach to Ingmar Bergman , South Salem, New York, 1981.

Cowie, Peter, Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography , New York, 1982.

Livingston, Paisley, Ingmar Bergman and the Ritual of Art , Ithaca, New York, 1982.

Marker, Lise-Lone, Ingmar Bergman: Four Decades in the Theater , New York, 1982.

Steene, Birgitta, A Reference Guide to Ingmar Bergman , Boston, 1982.

Lefèvre, Raymond, Ingmar Bergman , Paris, 1983.

Dervin, Daniel, Through a Freudian Lens Deeply: A Psychoanalysis of Cinema , Hillsdale, New Jersey, 1985.

Gado, Frank, The Passion of Ingmar Bergman , Durham, North Carolina, 1986.

Ketcham, Charles B., The Influence of Existentialism on Ingmar Bergman: An Analysis of the Theological Ideas Shaping a Filmmaker's Art , Lewiston, New York, 1986.

Steene, Birgitta, Ingmar Bergman: A Guide to References and Resources, Boston, 1987.

Lauder, Robert E., God, Death, Art, and Love: The Philosophical Vision of Ingmar Bergman , Mahwah, New Jersey, 1989.

Marty, Joseph, Ingmar Bergman, une poetique du desir , Paris, 1991.

Cowie, Peter, Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography , New York, 1992.

Marker, Lise-Lone, Ingmar Bergman: A Life in the Theater , New York, 1992.

Bragg, Melvin, The Seventh Seal , London, 1993.

Cohen, Hubert I., Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession , Boston, 1993.

Gibson, Arthur, The Rite of Redemption in the Films of Ingmar Bergman , Lewiston, Maine, 1993.

Tornqvist, Egil, Filmdiktaren Ingmar Bergman , Stockholm, 1993.

Long, Robert Emmet, Ingmar Bergman: Film and Stage , New York, 1994.

Tornqvist, Egil, Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs (Film Culture in Transition) , Amsterdam University Press, 1996.

Johns Blackwell, Marilyn, Gender and Representation in the Films of Ingmar Bergman (Studies in Scandinavian Literature and Culture ), Camden House, 1997.

Vermilye, Jerry, Ingmar Bergman: His Films and Career , Birch Lane Press, 1998.

Gervais, Marc, and Liv Ullmann, Ingmar Bergman: Magician and Prophet , McGill Queens University Press, 1999.

On BERGMAN: articles—

Ulrichsen, Erik, "Ingmar Bergman and the Devil," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1958.

Godard, Jean-Luc, "Bergmanorama," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July 1958.

Archer, Eugene, "The Rack of Life," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1959.

Alpert, Hollis, "Bergman as Writer," in Saturday Review (New York), 27 August 1960.

Alpert, Hollis, "Style Is the Director," in Saturday Review (New York), 23 December 1961.

Nykvist, Sven, "Photographing the Films of Ingmar Bergman," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), October 1962.

Persson, Göran, "Bergmans trilogi," in Chaplin (Stockholm), no. 40, 1964.

Fleisher, Frederic, "Ants in a Snakeskin," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1965.

Lefèvre, Raymond, "Ingmar Bergman," in Image et Son (Paris), March 1969.

"Director of the Year," International Film Guide (London, New York), 1973.

Sammern-Frankenegg, Fritz, "Learning 'A Few Words in the Foreign Language': Ingmar Bergman's 'Secret Message' in the Imagery of Hand and Face," in Scandinavian Studies , Summer 1977.

Sorel, Edith, "Ingmar Bergman: I Confect Dreams and Anguish," in New York Times , 22 January 1978.

Kinder, Marsha, " From the Life of the Marionettes to The Devil's Wanton ," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1981.

Lundell, T., and A. Mulac, "Husbands and Wives in Bergman Films: A Close Analysis Based on Empirical Data," in Journal of University Film Association (Carbondale, Illinois), Winter 1981.

Nave, B., and H. Welsh, "Retour de Bergman: Au ciné-club et au stage de Boulouris," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), April-May 1982.

Cowie, Peter, "Bergman at Home," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1982.

Corliss, Richard, and W. Wolf, "God, Sex, and Ingmar Bergman," in Film Comment (New York), May-June 1983.

McLean, T., "Knocking on Heaven's door," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), June 1983.

Boyd, D., " Persona and the Cinema of Representation," in Film Quarterly (Los Angeles), Winter 1983–84.

Tornqvist, E., "August StrindBERGman Ingmar," in Skrien (Amsterdam), Winter 1983–84.

Koskinen, M., "The Typically Swedish in Ingmar Bergman," in 25th Anniversary issue of Chaplin (Stockholm), 1984.

Ingemanson, B., "The Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman: Personification and Olfactory Detail," and J.F. Maxfield, "Bergman's Shame : A Dream of Punishment," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), January 1984.

"Dialogue on Film: Sven Nykvist," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), March 1984.

"Ingmar Bergman Section" of Positif (Paris), March 1985.

Barr, Alan P., "The Unraveling of Character in Bergman's Persona ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 15, no. 2, 1987.

O'Connor, John J., "Museum Tribute to Ingmar Bergman," in New York Times , 18 February 1987.

Chaplin (Stockholm), no. 30, vol 2/3, 1988.

American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1988.

Corliss, Richard, "The Glass Eye," in Film Comment (New York), November-December 1988.

Tobin, Yann, article in Positif (Paris), December 1988.

Lohr, S., "For Bergman, a New Twist on an Old Love," in New York Times , 6 September 1989.

"Bille August to Helm Script by Bergman," in Variety (New York), 13 September 1989.

Nystedt, H., article in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 32, no. 1, 1990.

Oliver, Roger W., "Bergman's Trilogy: Tradition and Innovation," in Performing Arts Journal (New York), January 1992.

Bonneville, L. "Les meilleures intentions. Par Ingmar Bergman," in Sequences , January 1993.

Kauffmann, Stanley, "The Abduction from the Theater: Mozart Opera on Film," in Yale Review (New Haven), January 1993.

Lahr, John, "Ingmar's Woman," in New Yorker (New York), 17 May 1993.

James, C. "Scenes from a Chilly Marriage," in New York Times , May 23, 1993.

"New York Institutions Honor Ingmar Bergman," in New York Times , 13 December 1994.

Riding, Alan, "Face to Face with a Life of Creation: At 76, the Eminent Director Ingmar Bergman Seems Even to Have His Demons under Control," in New York Times , 30 April 1995.

Murphy, Kathleen, "A Clean, Well-lighted Place: Ingmar Bergman's Dollhouse," in Film Comment (New York), May-June 1995.

James, Caryn, "Sweden's Poet of Film and Stagecraft," in New York Times , 5 May 1995

Jefferson, Margo, "Bergman Conquers, Not Once but Twice," in New York Times , 18 June 1995.

Bird, M., "Secret Arithmetic of the Soul: Music as a Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman," in Kinema (Water-loo), Spring 1996.

Koskinen, M., "'Everything Represents, Nothing Is,': Some Relations between Ingmar Bergman's Films and Theatre Productions," in Canadian Journal of Film Studies (Ottawa), vol. 6, no. 1, 1997.

Thompson, R., "Bergman's Women," in Moviemaker (Pasadena), May/June/July 1997.

Amiel, Vincent, "Du monde et de soi-même, l'éternel spectateur," in Positif (Paris), May 1998.

Wickbom, Kaj, "Den unge Ingmar Bergman," in Filmrutan (Sundsvall), 1998.

On BERGMAN: films—

Greenblatt, Nat, producer, The Directors , 1963 (appearance).

Donner, Jörn, director, Tre scener med Ingmar Bergman (Three Scenes with Ingmar Bergman) (for Finnish TV), 1975.

Donner, Jörn, director, The Bergman File , 1978.

* * *

Ingmar Bergman's unique international status as a filmmaker would seem assured on many grounds. His reputation can be traced to such diverse factors as his prolific output of largely notable work (40 features from 1946–82); the profoundly personal nature of his best films since the 1950s; the innovative nature of his technique combined with its essential simplicity, even when employing surrealistic and dream-like treatments (as, for example, in Wild Strawberries and Persona ); his creative sensitivity in relation to his players; and his extraordinary capacity to evoke distinguished acting from his regular interpreters, notably Gunnar Björnstrand, Max von Sydow, Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, and Liv Ullmann.

After an initial period of derivative, melodramatic filmmaking largely concerned with bitter man-woman relationships ("I just grabbed helplessly at any form that might save me, because I hadn't any of my own," he confesses in Bergman on Bergman ), Bergman reached an initial maturity of style in Summer Interlude and Summer with Monika , romantic studies of adolescent love and subsequent disillusionment. In The Naked Night he used a derelict travelling circus—its proprietor paired with a faithless young mistress and its clown with a faithless middle-aged wife—as a symbol of human suffering through misplaced love and to portray the ultimate loneliness of the human condition, a theme common to much of his work. Not that Bergman's films are all gloom and disillusionment. He has a recurrent, if veiled, sense of humour. His comedies, such as A Lesson in Love and Smiles of a Summer Night , are ironically effective ("You're a gynecologist who knows nothing about women," says a man's mistress in A Lesson in Love ), and even in Wild Strawberries the aged professor's relations with his housekeeper offer comic relief. Bergman's later comedies, the Shavian The Devil's Eye and Now About All These Women , are both sharp and fantastic.

"To me, religious problems are continuously alive . . . not . . . on the emotional level, but on an intellectual one," wrote Bergman at the time of Wild Strawberries. The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light , and The Silence lead progressively to the rejection of religious belief, leaving only the conviction that human life is haunted by "a virulent, active evil." The crusading knight of The Seventh Seal who cannot face death once his faith is lost survives only to witness the cruelty of religious persecution. In Bergman's view, faith belongs to the simple-minded and innocent. The Virgin Spring exposes the violence of vengeance in a period of primitive Christianity.

Bergman no longer likes these films, considering them "bogus"; nevertheless, they are excellently made in his highly professional style. Disillusionment with Lutheran denial of love is deep in Winter Light. "In Winter Light I swept my house clean," Bergman has said. Other Bergman films reflect his views on religion as well: the mad girl in Through a Glass Darkly perceives God as a spider, while the ailing sister in The Silence faces death with a loneliness that passes all understanding as a result of the frigid silence of God in the face of her sufferings. In The Face , however, Bergman takes sardonic delight in letting the rationalistic miracle-man suspect in the end that his bogus miracles are in fact genuine.

With Wild Strawberries , Bergman turned increasingly to psychological dilemmas and ethical issues in human and social relations once religion has proved a failure. Above all else, the films suggest, love, understanding, and common humanity seem lacking. The aged medical professor in Wild Strawberries comes through a succession of dreams to realize the truth about his cold and loveless nature. In Persona , the most psychologically puzzling, controversial, yet significant of all Bergman's films—with its Brechtian alienation technique and surreal treatment of dual personality—the self-imposed silence of the actress stems from her failure to love her husband and son, though she responds with horror to the self-destructive violence of the world around her. This latter theme is carried still further in The Shame , in which an egocentric musician attempts non-involvement in his country's war only to collapse into irrational acts of violence himself through sheer panic. The Shame and Hour of the Wolf are concerned with artists who are too self-centered to care about the larger issues of the society in which they live.

"It wasn't until A Passion that I really got to grips with the man-woman relationship," says Bergman. A Passion deals with "the dark, destructive forces" in human nature which sexual urges can inspire. Bergman's later films reflect, he claims, his "ceaseless fascination with the whole race of women," adding that "the film . . . should communicate psychic states." The love and understanding needed by women is too often denied them, suggests Bergman. Witness the case of the various women about to give birth in Brink of Life and the fearful, haunted, loveless family relationships in Cries and Whispers. The latter, with The Shame and The Serpent's Egg , is surely among the most terrifying of Bergman's films, though photographed in exquisite color by Sven Nykvist, his principal cinematographer.

Man-woman relationships are successively and uncompromisingly examined in a series of Bergman films. The Touch shows a married woman driven out of her emotional depth in an extramarital affair; Face to Face , one of Bergman's most moving films, concerns the nervous breakdown of a cold-natured woman analyst and the hallucinations she suffers; and a film made as a series for television (but reissued more effectively in a shortened, re-edited form for the cinema, Scenes from a Marriage ) concerns the troubled, long-term love of a professional couple who are divorced but unable to endure separation. Supreme performances were given by Bibi Andersson in Persona and The Touch , and by Liv Ullmann in Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage and Face to Face. Bergman's later films, made in Sweden or during his period of self-imposed exile, are more miscellaneous. The Magic Flute is one of the best, most delightful of opera-films. The Serpent's Egg is a savage study in the sadistic origins of Nazism, while Autumn Sonata explores the case of a mother who cannot love. Bergman declared his filmmaking at an end with his brilliant, German-made misanthropic study of a fatal marriage, From the Life of the Marionettes , and the semi-autobiographical television series Fanny and Alexander. Swedish-produced, the latter work was released in a re-edited version for the cinema. Set in 1907, Fanny and Alexander is the gentle, poetic story of two years in the lives of characters who are meant to be Bergman's maternal grandparents.

After Fanny and Alexander , Bergman directed After the Rehearsal , a small-scale drama which reflected his growing preoccupation with working in the theater. It features three characters: an aging, womanizing stage director mounting a version of Strindberg's The Dream Play ; the attractive, determined young actress who is his leading lady; and his former lover, once a great star but now an alcoholic has-been, who accepts a humiliating bit role in the production.

After the Rehearsal was not Bergman's cinematic swan song. He went on to author two scripts which are autobiographical outgrowths of Fanny and Alexander. The Best Intentions , directed by Bille August, is a compassionate chronicle of ten years in the tempestuous courtship and early marriage of Bergman's parents. His father starts out as an impoverished theology student who is unyielding in his views. His mother is spirited but pampered, the product of an upper-class upbringing. The film also is of note for the casting of Max von Sydow as the filmmaker's maternal grandfather. The actor's presence is most fitting, given the roots of the scenario and his working relationship with Bergman, which dates back to the 1950s.

The Best Intentions was followed by Sunday's Children , directed by Bergman's son Daniel. The film is a deeply personal story of a ten-year-old boy named Pu, who is supposed to represent the young Ingmar Bergman. Pu is growing up in the Swedish countryside during the 1920s. The scenario focuses on his relationship to his minister father and other family members; also depicted is the adult Pu's unsettling connection to his elderly dad.

—Roger Manvell, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: