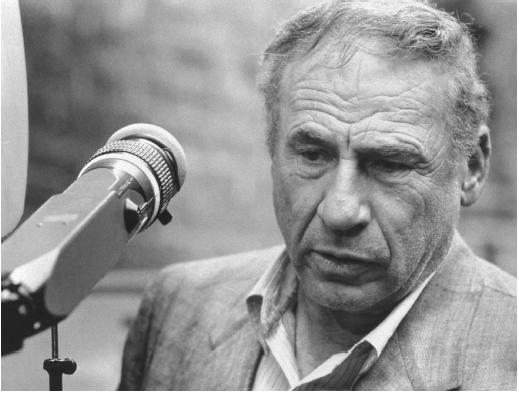

Mel Brooks - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Melvin Kaminsky in Brooklyn, New York, 28 June 1926.

Education:

Attended Virginia Military Institute, 1944.

Family:

Married 1) Florence Baum (divorced), two sons, one daughter; 2) actress

Anne Bancroft, one son.

Military Service:

Combat engineer, U.S. Army, 1944–46.

Career:

Jazz drummer, stand-up comedian, and social director at

Grossinger's resort; writer for Sid Caesar's "Your

Show of Shows," 1954–57; conceived, wrote, and narrated

cartoon short

The Critic

, 1963; co-creator (with Buck Henry) of

Get Smart

TV show, 1965; directed first feature,

The Producers

, 1968; founder, Brooksfilms, 1981.

Awards:

Academy Award for Best Short Subject, for

The Critic

, 1964; Academy Award for Best Story and Screenplay, and Writers Guild

Award for Best Written Screenplay, for

The Producers

, 1968; Academy Award nomination, Best Song, for

Blazing Saddles

, 1974; Academy Award nomination, Best Screenplay, for

Young Frankenstein

, 1975; American Comedy Awards Lifetime Achievement Award, 1987.

Address:

Brooksfilms, Ltd., Culver Studios, 9336 W. Washington Blvd., Culver City,

CA 90212, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1963

-

The Critic (cartoon) (+ sc, narration)

- 1968

-

The Producers (+ sc, voice)

- 1970

-

The Twelve Chairs (+ co-sc, role)

- 1974

-

Blazing Saddles (+ co-sc, mus, role); Young Frankenstein (+ co-sc)

- 1976

-

Silent Movie (+ co-sc, role)

- 1977

-

High Anxiety (+ pr, co-sc, mus, role)

- 1981

-

The History of the World, Part I (+ pr, co-sc, mus, role)

- 1983

-

To Be or Not to Be (+ pr, co-sc, role)

- 1987

-

Spaceballs (+ pr, co-sc, role)

- 1991

-

Life Stinks! (+ co-sc, role)

- 1993

-

Robin Hood: Men in Tights (+ co-sc, role)

- 1995

-

Dracula: Dead and Loving It (co-sc, role, pr)

Films as Executive Producer:

- 1980

-

The Elephant Man (Lynch)

- 1985

-

The Doctor and the Devils (Francis)

- 1986

-

The Fly (Cronenberg); Solarbabies (Johnson)

- 1987

-

84 Charing Cross Road (Jones)

- 1992

-

The Vagrant (Walas)

Other Films:

- 1979

-

The Muppet Movie (Frawley) (role)

- 1991

-

Look Who's Talking, Too! (Heckerling) (voice, role)

- 1994

-

Il silenzio dei prosciutti ( The Silence of the Hams ) (Greggio) (role); The Little Rascals (Spheeris) (role)

- 1997

-

I Am Your Child (for TV) (as himself)

- 1998

-

The Prince of Egypt (Chapman, Hickner) (role)

- 1999

-

Svitati (Greggio) (co-sc, ro)

Publications

By BROOKS: books—

Silent Movie , New York, 1976.

The History of the World, Part I , New York, 1981.

The 2,000 Year Old Man in the Year 2000, The Book: Including How to Not Die and Other Good Tips , with Carl Reiner, HarperPerennial Library, 1998.

By BROOKS: articles—

"Confessions of an Auteur," in Action (Los Angeles), November/December 1971.

Interview with James Atlas, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1975.

"Fond Salutes and Naked Hate," interview with Gordon Gow, in Films and Filming (London), July 1975.

Interview with A. Remond, in Ecran (Paris), November 1976.

"Comedy Directors: Interview with Mel Brooks," with R. Rivlin, in Millimeter (New York), October and December 1977.

Interview with Alan Yentob, in Listener (London), 8 October 1981.

Interview in Time Out (London), 16 February 1984.

Interview in Screen International , 3 March 1984.

Interview in Hollywood Reporter , 27 October 1986.

"The Playboy Interview," interview with L. Stegel in Playboy (Chicago), January 1989.

"Mel Brooks: Of Woody, the Great Caesar, Flop Sweat and Cigar Smoke," People Weekly (New York), Summer 1989 (special issue).

On BROOKS: books—

Adler, Bill, and Jeffrey Fineman, Mel Brooks: The Irreverent Funnyman , Chicago, 1976.

Bendazzi, G., Mel Brooks: l'ultima follia di Hollywood , Milan, 1977.

Holtzman, William, Seesaw: A Dual Biography of Anne Bancroft and Mel Brooks , New York, 1979.

Allen, Steve, Funny People , New York, 1981.

Yacowar, Maurice, Method in Madness: The Comic Art of Mel Brooks , New York, 1981.

Smurthwaite, Nick, and Paul Gelder, Mel Brooks and the Spoof Movie , London, 1982.

Squire, Jason, E., The Movie Business Book , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1983.

On BROOKS: articles—

"Two Thousand Year Old Man," in Newsweek (New York), 4 October 1965.

Diehl, D., "Mel Brooks," in Action (Los Angeles), January/February 1975.

Lees, G., "The Mel Brooks Memos," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1977.

Carcassonne, P., "Dossier: Hollywood 79: Mel Brooks," in Cinématographe (Paris), March 1979.

Karoubi, N., "Mel Brooks Follies," in Cinéma (Paris), February 1982.

"Mel Brooks," in Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 26: American Screenwriters , Detroit, 1984.

Erens, Patricia, "You Could Die Laughing: Jewish Humor and Film," in East-West Film Journal (Honolulu), no. 1, 1987.

Carter, E.G., "The Cosmos according to Mel Brooks," in Vogue (New York), June 1987.

Dougherty, M., "May the Farce Be with Him: Spaceballs Rockets Mel Brooks Back into the Lunatic Orbit," in People Weekly (New York), 20 July 1987.

Frank, A., "Mel's Crazy Movie World," in Photoplay Movies & Video (London), January 1988.

Goldstein, T., "A History of Mel Brooks: Part I," in Video (New York), March 1988.

Stauth, C., "Mel and Me," in American Film (Los Angeles), April 1990.

Radio Times , 4 April 1992.

Segnocinema (Vicenza), March-April 1994.

Greene, R., "Funny You Should Ask," in Boxoffice (Chicago), December 1995.

* * *

Mel Brooks's central concern (with High Anxiety and To Be or Not to Be as possible exceptions) is the pragmatic, absurd union of two males, starting with the more experienced member trying to take advantage of the other, and ending in a strong friendship and paternal relationship. The dominant member of the duo, confident but illfated, is Zero Mostel in The Producers , Frank Langella in The Twelve Chairs , and Gene Wilder in Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein. The second member of the duo, usually physically weak and openly neurotic, represents the victim who wins, who learns from his experience and finds friendship to sustain him. These "Jewish weakling" characters include Wilder in The Producers , Ron Moody, and Cleavon Little. Though this character, as in the case of Little, need not literally be Jewish, he displays the stereotypical characteristics.

Women in Brooks's films are grotesque figures, sex objects ridiculed and rejected. They are either very old or sexually gross and simple. The love of a friend is obviously worth more than such an object. The secondary male characters, befitting the intentional infantilism of the films, are men-babies given to crying easily. They are set up as examples of what the weak protagonist might become without the paternal care of his reluctant friend. In particular, Brooks sees people who hide behind costumes—cowboy suits, Nazi uniforms, clerical garb, homosexual affectations—as silly children to be made fun of.

The plots of Brooks's films deal with the experienced and inexperienced men searching for a way to triumph in society. They seek a generic solution or are pushed into one. Yet there is no escape into generic fantasy in the Brooks films, since the films take place totally within the fantasy. There is no regard, as in Woody Allen's films, for the pathetic nature of the protagonist in reality. In fact, the Brooks films reverse the Allen films' endings as the protagonists move into a comic fantasy of friendship. (A further contrast with Allen is in the nature of the jokes and gags. Allen's humor is basically adult embarrassment; Brooks's is infantile taboo-breaking.)

In The Producers the partners try to manipulate show business and wind up in jail, planning another scheme because they enjoy it. In The Twelve Chairs they try to cheat the government; at the end Langella and Moody continue working together though they no longer have the quest for the chairs in common. In Blazing Saddles Little and Wilder try to take a town; it ends with the actors supposedly playing themselves, getting into a studio car and going off together as pals into the sunset. In these films it is two men alone against a corrupt and childish society. Though their schemes fall apart—or are literally exploded as in The Producers and The Twelve Chairs —they still have each other.

Young Frankenstein departs from the pattern with each of the partners, monster and doctor, sexually committed to women. While the basic pattern of male buddies continued when Brooks began to act in his own films, he also winds up with the woman when he is the hero star ( High Anxiety, Silent Movie, The History of the World, To Be or Not to Be ). It is interesting that Brooks always tries to distance himself from the homosexual implications of his central theme by including scenes in which overtly homosexual characters are ridiculed. It is particularly striking that these characters are, in The Producers, Blazing Saddles , and The Twelve Chairs , stage or film directors.

Brooks's late-career films have been collectively disappointing. Upon its release, Spaceballs already was embarrassingly dated. It is meant to be a spoof of Star Wars , yet it came to movie screens a decade after the sci-fi epic. Comic timing used to be Brooks's strong point, yet the story has no momentum and the film's funniest line—"May the Schwartz be with you"—is repeated so often that the joke quickly becomes stale.

The bad-taste scenes in Brooks's earlier films, most memorably Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein , used to be considered provocative. Now that young filmmakers and television writers have stretched comedy to the extreme limits, Brooks has lost his ability to astound and appall the audience. His most recent feature, Robin Hood: Men in Tights , a parody of Errol Flynn-style swashbuckling adventures, is sorely lacking in laughs. The sole exception: Dom DeLuise's hilarious (but all too brief) Godfather spoof.

Life Stinks! is the most serious of all of Brooks's films. Rather than being a string of quick gags, it offers a slower-paced, more conventional narrative. As with To Be or Not to Be (which is set in Poland at the beginning of World War II), he treats a sobering theme in a comic manner as he comments on the plight of the homeless. But while To Be or Not to Be is as deeply moving as it is funny, Life Stinks! stinks. It is episodic and all too often flat, with its satire much too broad and all too rarely funny.

—Stuart M. Kaminsky, updated by Audrey E. Kupferberg

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: