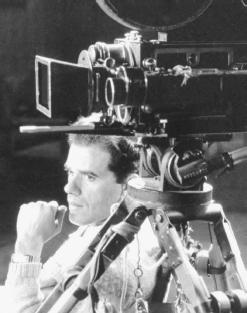

Frank Capra - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Bisaquino, Sicily, 18 May 1897; emigrated with family to Los Angeles, 1903. Education: Manual Arts High School, Los Angeles; studied chemical engineering at California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, graduated 1918. Family: Married 1) Helen Howell, 1924 (divorced 1938); 2) Lucille Reyburn, 1932, two sons, one daughter, Ballistics teacher, U.S. Army, 1918–19. Career: Lab assistant for Walter Bell, 1922–23; prop man, editor for Bob Eddy, writer for Hal Roach and Mack Sennett, 1923–25; hired by Columbia Pictures, 1928; began to work with Robert Riskin, 1931; elected President of Academy, 1935; elected President of Screen Directors' Guild, 1938; formed Frank Capra Productions with writer Robert Riskin, 1939; Major in Signal Corps, 1942–45; formed Liberty Films with Sam Briskin, William

Films as Director:

- 1922

-

Fultah Fisher's Boarding House

- 1926

-

The Strong Man (+ co-sc)

- 1927

-

Long Pants ; For the Love of Mike

- 1928

-

That Certain Thing ; So This Is Love ; The Matinee Idol ; The Way of the Strong ; Say It with Sables (+ co-story); Submarine ; The Power of the Press ; The Swim Princess ; The Burglar ( Smith's Burglar )

- 1929

-

The Younger Generation ; The Donovan Affair ; Flight (+ dialogue)

- 1930

-

Ladies of Leisure ; Rain or Shine

- 1931

-

Dirigible ; The Miracle Woman ; Platinum Blonde

- 1932

-

Forbidden (+ sc); American Madness

- 1933

-

The Bitter Tea of General Yen (+ pr); Lady for a Day

- 1934

-

It Happened One Night ; Broadway Bill

- 1936

-

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (+ pr)

- 1937

-

Lost Horizon (+ pr)

- 1938

-

You Can't Take It with You (+ pr)

- 1939

-

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (+ pr)

- 1941

-

Meet John Doe (+ pr)

- 1942

-

Why We Fight (Part 1): Prelude to War (+ pr)

- 1943

-

Why We Fight (Part 2): The Nazis Strike (co-d, pr); Why We Fight (Part 3): Divide and Conquer (co-d, pr)

- 1944

-

Why We Fight (Part 6): The Battle of China (co-d, pr); Tunisian Victory (co-d, pr); Arsenic and Old Lace (+ pr) (filmed in 1942)

- 1945

-

Know Your Enemy: Japan (co-d, pr); Two Down, One to Go (+ pr)

- 1946

-

It's a Wonderful Life (+ pr, co-sc)

- 1948

-

State of the Union (+ pr)

- 1950

-

Riding High (+ pr)

- 1951

-

Here Comes the Groom (+ pr)

- 1956

-

Our Mr. Sun (+ pr, sc) (Bell System Science Series Numbers 1 to 4)

- 1957

-

Hemo the Magnificent (+ pr, sc); The Strange Case of the Cosmic Rays (+ pr, co-sc)

- 1958

-

The Unchained Goddess (+ pr, co-sc)

- 1959

-

A Hole in the Head (+ pr)

- 1961

-

Pocketful of Miracles (+ pr)

Other Films:

- 1924

-

(as co-sc with Arthur Ripley on films featuring Harry Longdon): Picking Peaches ; Smile Please ; Shanghaied Lovers ; Flickering Youth ; The Cat's Meow ; His New Mama ; The First Hundred Years ; The Luck o' the Foolish ; The Hansom Cabman ; All Night Long ; Feet of Mud

- 1925

-

(as co-sc with Arthur Ripley on films featuring Harry Langdon): The Sea Squawk ; Boobs in the Woods ; His Marriage Wow ; Plain Clothes ; Remember When? ; Horace Greeley Jr. ; The White Wing's Bride ; Lucky Stars ; There He Goes ; Saturday Afternoon

- 1926

-

(as co-sc with Arthur Ripley on films featuring Harry Langdon): Fiddlesticks ; The Soldier Man ; Tramp, Tramp, Tramp

- 1943

-

Why We Fight (Part 4): The Battle of Britain (pr)

- 1944

-

The Negro Soldier (pr); Why We Fight (Part 5): The Battle of Russia (pr); Know Your Ally: Britain (pr)

- 1945

-

Why We Fight (Part 7): War Comes to America (pr); Know Your Enemy: Germany (pr)

- 1950

-

Westward the Women (story)

- 1973

-

Frank Capra (Schickel) (as himself)

- 1980

-

Hollywood (Brownlow, Gill—doc) (as himself)

- 1982

-

The 10th American Film Institute Life Achievement Award: A Salute to Frank Capra

- 1984

-

George Stevens: A Filmmaker's Journey (as himself)

Publications

By CAPRA: books—

The Name above the Title , New York, 1971.

It's a Wonderful Life , with Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, New York, 1986.

By CAPRA: articles—

"The Gag Man," in Breaking into Movies , edited by Charles Jones, New York, 1927.

"Sacred Cows to the Slaughter," in Stage (New York), 13 July 1936.

"We Should All Be Actors," in Silver Screen (New York), September 1946.

"Do I Make You Laugh?," in Films and Filming (London), September 1962.

"Capra Today," with James Childs, in Film Comment (New York), vol.8, no.4, 1972.

"Mr. Capra Goes to College," with Arthur Bressan and Michael Moran, in Interview (New York), June 1972.

"Why We (Should Not) Fight," interview with G. Bailey, in Take One (Montreal), September 1975.

"'Trends Change Because Trends Stink'—An Outspoken Talk with Legendary Producer/Director Frank Capra," with Nancy Anderson, in Photoplay (New York), November 1975.

Interview with J. Mariani, in Focus on Film (London), no.27, 1977.

"Dialogue on Film," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1978.

Interview with H.A. Hargreave, in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 9, no. 3, 1981.

On CAPRA: books—

Griffith, Richard, Frank Capra , London, 1951.

Silke, James, Frank Capra: One Man—One Film , Washington, D.C., 1971.

Bergman, Andrew, We're in the Money: Depression America and Its Films , New York, 1972.

Willis, Donald, The Films of Frank Capra , Metuchen, New Jersey, 1974.

Glatzer, Richard, and John Raeburn, editors, Frank Capra: The Man and His Films , Ann Arbor, 1975.

Poague, Leland, The Cinema of Frank Capra: An Approach to Film Comedy , South Brunswick, New Jersey, 1975.

Bohn, Thomas, An Historical and Descriptive Analysis of the 'Why We Fight' Series , New York, 1977.

Maland, Charles, American Visions: The Films of Chaplin, Ford, Capra and Welles, 1936–1941 , New York, 1977.

Scherle, Victor, and William Levy, The Films of Frank Capra , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1977.

Bohnenkamp, Dennis, and Sam Grogg, editors, Frank Capra Study Guide , Washington, D.C., 1979.

Maland, Charles, Frank Capra , Boston, 1980.

Giannetti, Louis, Masters of the American Cinema , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1981.

Zagarrio, Vito, Frank Capra , Florence 1985.

Carney, Raymond, American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra , Cambridge, 1986.

Lazere, Donald, editor, American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives , Berkeley, 1987.

Wolfe, Charles, Frank Capra: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1987.

McBride, Joseph, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success , New York, 1992.

On CAPRA: articles—

"How Frank Capra Makes a Hit Picture," in Life (New York), 19 September 1938.

Hellman, Geoffrey, "Thinker in Hollywood," in New Yorker , 5 February 1940.

Ferguson, Otis, "Democracy at the Box Office," in New Republic (New York), 24 March 1941.

Salemson, Harold, "Mr. Capra's Short Cuts to Utopia," in Penguin Film Review no.7, London, 1948.

Deming, Barbara, "Non-Heroic Heroes," in Films in Review (New York), April 1951.

"Capra Issue" of Positif (Paris), December 1971.

Richards, Jeffrey, "Frank Capra: The Classic Populist," in Visions of Yesterday , London, 1973.

Nelson, J., "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: Capra, Populism, and Comic-Strip Art," in Journal of Popular Film (Bowling Green, Ohio), Summer 1974.

Badder, D.J., "Frank Capra," in Film Dope (London), November 1974 and October 1975.

"Capra Issue" of Film Comment (New York), vol.8, no.4, 1972.

Sklar, Robert, "The Making of Cultural Myths: Walt Disney and Frank Capra," in Movie-made America , New York, 1975.

"Lost and Found: The Films of Frank Capra," in Film (London), June 1975.

Rose, B., "It's a Wonderful Life: The Stand of the Capra Hero," in Journal of Popular Film (Bowling Green, Ohio), vol.6, no.2, 1977.

Quart, Leonard, "Frank Capra and the Popular Front," in Cineaste (New York), Summer 1977.

Gehring, Wes, "McCarey vs. Capra: A Guide to American Film Comedy of the '30s," in Journal of Popular Film and Television (Bowling Green, Ohio), vol.7, no.1, 1978.

Dickstein, M., "It's a Wonderful Life, But. . . ," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), May 1980.

Jameson, R.T., "Stanwyck and Capra," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1981.

"Capra Issue" of Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Winter 1981.

Basinger, Jeanine, "America's Love Affair with Frank Capra," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), March 1982.

Edgerton, G., "Capra and Altman: Mythmaker and Mythologist," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), January 1983.

Dossier on Capra, in Positif (Paris), July-August 1987.

American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1987.

Gottlieb, Sidney, "From Heroine to Brat: Frank Capra's Adaptation of "Night Bus" ( It Happened One Night )," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 16, no. 2, 1988.

Baker, R., "Capra Beats the Game," in New York Times , 10 September 1991.

Obituary, in Newsweek , 16 September 1991.

Obituary, in Time , 16 September 1991.

Obituary, in Film Monthly (Berkhamstead), November 1991.

Everschor, Franz, "Mr. Perot geht nicht nach Washington," in Film-dienst (Cologne), 4 August 1992.

Smoodin, Eric, "'Compulsory' Viewing for Every Citizen: Mr. Smith and the Rhetoric of Reception," in Cinema Journal (Austin), Winter 1996.

Fallows, Randall, "George Bailey in the Vital Center: Postwar Liberal Politics and It's a Wonderful Life," in Joural of Popular Film & Television (Washington, D.C.), Summer 1997.

Santaolalla, Isabel C., "East Is East and West Is West? Otherness in Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen, " in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), January 1998.

* * *

The critical stock of Frank Capra has fluctuated perhaps more wildly than that of any other major director. During his peak years, the 1930s, he was adored by the press, by the industry and, of course, by audiences. In 1934 It Happened One Night won nearly all the Oscars, and through the rest of the decade a film of Frank Capra was either the winner or the strong contender for that honor. Long before the formulation of the auteur theory, the Capra signature on a film was recognized. But after World War II his career went into serious decline. His first post-war film, It's a Wonderful Life , was not received with the enthusiasm he thought it deserved (although it has gone on to become one of his most-revered films). Of his last five films, two are remakes of material he treated in the thirties. Many contemporary critics are repelled by what they deem indigestible "Capracorn" and have even less tolerance for an ideology characterized as dangerously simplistic in its populism, its patriotism, its celebration of all-American values.

Indeed, many of Capra's most famous films can be read as excessively sentimental and politically naive. These readings, however, tend to neglect the bases for Capra's success—his skill as a director of actors, the complexity of his staging configurations, his narrative economy and energy, and most of all, his understanding of the importance of the spoken word in sound film. Capra captured the American voice in cinematic space. The words often serve the cause of apple pie, mom, the little man and other greeting card clichés (indeed, the hero of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town writes verse for greeting cards). But often in the sound of the voice we hear uncertainties about those very clichés.

Capra's career began in the pre-talkie era, when he directed silent comic Harry Langdon in two successful films. His action films of the early thirties are not characteristic of his later work, yet already, in the films he made with Barbara Stanwyck, his individual gift can be discerned. The narrative pretext of The Miracle Woman is the urgency of Stanwyck's voice, its ability to move an audience, to persuade listeners of its sincerity. Capra exploited the raw energy of Stanwyck in this and other roles, where her qualities of fervor and near-hysterical conviction are just as essential to her persona as her hard-as-nails implacability would be in the forties. Stanwyck's voice is theatricalized, spatialized in her revivalist circus-tent in The Miracle Woman and on the hero's suicide tower in Meet John Doe , where her feverish pleadings are the only possible tenor for the film's unresolved ambiguities about society and the individual.

John Doe is portrayed by Gary Cooper, another American voice with particular resonance in the films of Capra. A star who seems to have invented the "strong, silent" type, Cooper first plays Mr. Deeds, whose platitudinous doggerel comes from a simple, do-gooder heart, but who enacts a crisis of communication in his long silence at the film's climax, a sanity hearing. When Mr. Deeds finally speaks it is a sign that the community (if not sanity) is restored—the usual resolution of a Capra film. As John Doe, Cooper is given words to voice by reporter Stanwyck, and he delivers them with such conviction that the whole nation listens. The vocal/dramatic center of the film is located in a rain-drenched ball park filled with John Doe's "people." The hero's effort to speak the truth, to reveal his own imposture and expose the fascistic intentions of his sponsor, is stymied when the lines of communication are literally cut between microphone and loudspeaker. The Capra narrative so often hinges on the protagonist's ability to speak and be heard, on the drama of sound and audition.

The bank run in American Madness is initiated by a montage of telephone voices and images, of mouths spreading a rumor. The panic is quelled by the speech of the bank president (Walter Huston), a situation repeated in more modest physical surroundings in It's a Wonderful Life. The most extended speech in the films of Capra occurs in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. The whole film is a test of the hero's voice, and it culminates in a filibuster, a speech that, by definition, cannot be interrupted. The climax of State of the Union involves a different kind of audience and audition. There, the hero confesses his political dishonesty and his love for his wife on television.

The visual contexts, both simple and complex, never detract from the sound of Capra's films. They enhance it. The director's most elaborately designed film, The Bitter Tea of General Yen (recalling the style of Josef von Sternberg in its chiaroscuro lighting and its exoticism) expresses the opposition of cultural values in its visual elements, to be sure, but also in the voices of Stanwyck and Nils Asther, a Swedish actor who impersonates a Chinese war lord. Less unusual but not less significant harmonies are sounded in It Happened One Night , where a society girl (Claudette Colbert) learns "real" American speech from a fast-talking reporter (Clark Gable). The love scenes in Mr. Deeds are for Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur, another quintessential Capra heroine, whose vocal personality is at least as memorable as her physical one. In James Stewart Capra finds his most disquieting voice, ranging in Mr. Smith from ingenuousness to hysterical desperation and in It's a Wonderful Life to an even higher pitch of hysteria when the hero loses his identity.

The sounds and sights of Capra's films bear the authority of a director whose autobiography is called The Name above the Title. With that authority comes an unsettling belief in authorial power, the power dramatized in his major films, the persuasiveness exercised in political and social contexts. That persuasion reflects back on the director's own power to engage the viewer in his fiction, to call upon a degree of belief in the fiction—even when we reject the meaning of the fable.

—Charles Affron

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: