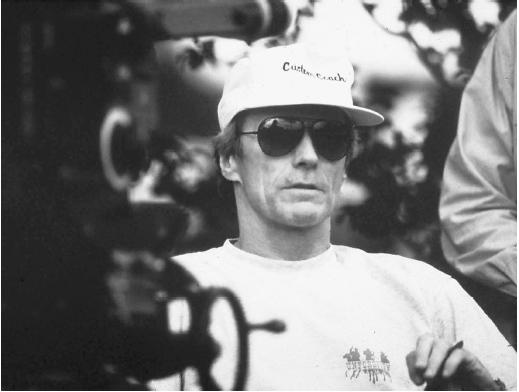

Clint Eastwood - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

31 May 1930 in San Francisco, California.

Education:

Oakland Technical High School; Los Angeles City College, 1953–54.

Military Service:

Drafted into the U.S. Army, 1950.

Family:

Married Maggie Johnson, 1953 (divorced, 1980); one son, one daughter.

Career:

Under contract with Universal, 1954–55; sporadic work in film,

late 1950s; played Rowdy Yates in TV series

Rawhide

, 1959–65; went to Europe to make three highly successful westerns

with Sergio Leone, 1965; returned to U.S., 1967; formed Malpaso production

company and directed first film,

Play Misty for Me

, 1971; first effort as producer,

Firefox

, 1982; Mayor of Carmel, California, 1986–88.

Awards:

Chevaliers des Lettres, France, 1985; Academy Awards, Best Director and

Best Picture, for

Unforgiven

, 1992; Fellowship of the British Film Institute, 1993; American Film

Institute Life Achievement Award, 1996; Honorary Cesar Award, 1998.

Address:

Malpaso Productions, 4000 Warner Boulevard, Burbank, California 91522,

USA.

Films as Director:

- 1971

-

Play Misty for Me (+ role)

- 1972

-

High Plains Drifter (+ role)

- 1973

-

Breezy

- 1975

-

The Eiger Sanction (+ role)

- 1976

-

The Outlaw Josey Wales (+ role)

- 1977

-

The Gauntlet (+ role)

- 1980

-

Bronco Billy (+ role, song composer)

- 1982

-

Firefox (+ role, pr); Honkytonk Man (+ role, pr)

- 1983

-

Sudden Impact (+ role, pr)

- 1985

-

Pale Rider (+ role, pr)

- 1986

-

Heartbreak Ridge (+ role, pr, song composer)

- 1987

-

Bird (+ pr)

- 1990

-

The Rookie (+ role); White Hunter, Black Heart (+ role, pr)

- 1992

-

Unforgiven (+ role, pr, music)

- 1993

-

A Perfect World (+ role, pr)

- 1995

-

The Bridges of Madison County (+ role, pr)

- 1997

-

Absolute Power (+ role, pr); Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (+pr)

- 1999

-

True Crime (+ role, pr)

- 2000

-

Space Cowboys (+ role, pr)

Other Films:

- 1955

-

Francis in the Navy (role); Lady Godiva (role); Revenge of the Creature (role); Tarantula (role)

- 1956

-

The First Travelling Saleslady (role); Never Say Goodbye (role); Star in the Dust (role)

- 1957

-

Escapade in Japan (role)

- 1958

-

Ambush at Cimarron Pass (role); Lefayette Escradille (role)

- 1964

-

A Fistful of Dollars (role)

- 1965

-

For a Few Dollars More (role)

- 1966

-

Il Buono, il brutto, il cattivo ( The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Leone) (role); Le Streghe (role)

- 1967

-

Hang 'em High (role)

- 1968

-

Coogan's Bluff (role)

- 1969

-

Paint Your Wagon (role); Where Eagles Dare (role)

- 1970

-

Kelly's Heroes (role); Two Mules for Sister Sara (role)

- 1971

-

The Beguiled (role); Dirty Harry (role)

- 1972

-

Joe Kidd (role)

- 1973

-

Magnum Force (role)

- 1974

-

Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (role)

- 1976

-

The Enforcer (role)

- 1978

-

Every Which Way but Loose (role)

- 1979

-

Escape from Alcatraz (role)

- 1980

-

Any Which Way You Can (role, song composer)

- 1984

-

City Heat (role); Tightrope (role, pr)

- 1988

-

The Dead Pool (role, pr); Thelonius Monk: Straight No Chaser (exec pr)

- 1989

-

The Pink Cadillac (role)

- 1993

-

In the Line of Fire (role)

- 1996

-

Wild Bill: Hollywood Maverick (doc) (role)

Publications

By EASTWOOD: book—

Clint Eastwood: Interviews , edited by Kathie Coblentz, Jackson, 1999.

By EASTWOOD: articles—

Interview with David Thomson in Film Comment , September/October 1984.

Interview with C. Tesson and O. Assayas in Cahiers du Cinéma , February 1985.

Interview with Michel Ciment and Hubert Niograt in Positif , July/August 1988.

Interview with Nat Hentoff in American Film , September 1988.

Interview with Allan Hunter in Films and Filming , November/December 1988.

Interview with R. Gentry in Film Quarterly , vol. 42, no. 3, 1989.

Interview with Michel Ciment in Positif , no. 351, 1990.

Interview with M. Henry in Positif , no. 380, 1992.

Interview with David Breskin, in Rolling Stone (New York), 17 September 1992.

Interview in Reel West , October/November 1992.

Interview with David Wild, in Rolling Stone (New York), 24 August 1995.

Interview with Ric Gentry, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1997.

Interview with M. Henry, in Positif (Paris), no. 445, 1998.

Interview with M. Henry, in Positif (Paris), no. 459, 1999.

On EASTWOOD: books—

Kaminsky, Stuart, Clint Eastwood , New York, 1974.

Agan, Patrick, Clint Eastwood: The Man behind the Myth , New York, 1975.

Downing, David, and Gary Herman, Clint Eastwood, All-American Anti-Hero: A Critical Appraisal of the World's Top Box Office Star and His Films , London, 1977.

Ferrari, Philippe, Clint Eastwood , Paris, 1980.

Johnstone, Iain, The Man with No Name: Clint Eastwood , London, 1981; revised edition 1988.

Zmijewsky, Boris, and Lee Pfeiffer, The Films of Clint Eastwood , Secaucas, NJ, 1982; revised editions, 1988 and 1993.

Cole, Gerald, and Peter Williams, Clint Eastwood , London, 1983.

Guerif, Francois, Clint Eastwood , Paris, 1983.

Rider, Jeffrey, Clint Eastwood , New York, 1987.

Lagarde, Helene, Clint Eastwood , Paris, 1988.

Weinberger, Michele, Clint Eastwood , Paris, 1989 .

Frayling, Christopher, Clint Eastwood , London, 1992.

Thompson, Douglas, Clint Eastwood: Riding High , Chicago, 1992.

Smith, Paul, Clint Eastwood: A Cultural Production , Minneapolis, 1993.

Bingham, Dennis, Acting Male: Masculinities in the Films of James Stewart, Jack Nicholson, and Clint Eastwood , New Brunswick, NJ, 1994.

Gallafent, Edward, Clint Eastwood: Filmmaker and Star , New York, 1994.

Ortoli, Philippe, Clint Eastwood: la figure du guerrier , Paris, 1994.

Schickel, Richard, Clint Eastwood: A Biography , New York, 1997.

On EASTWOOD: articles—

Patterson, E., "Every Which Way but Lucid: The Critique of Authority in Clint Eastwood's Police Films," in Journal of Popular Film , Fall 1982.

"Clint Eastwood section" of Positif , January 1985.

Kehr, Dave, "A Fistful of Eastwood," in American Film , March 1985.

Chevrie, M., and D. J. Wiener, "Le dernier des cow-boys," in Cahiers du Cinéma , March 1987.

Holmlund, C., "Sexuality and Power in Male Doppelganger Cinema: The Case of Clint Eastwood and Tightrope ," in Cinema Journal , vol. 26, no. 1, 1986.

Bingham, D., "Men with No Names: Clint Eastwood, the Stranger Persona, Identification, and the Impenetrable Gaze," in Journal of Film and Video , vol. 42, no. 4, 1990.

Combs, Richard, "Shadowing the Hero," in Sight and Sound , October 1992.

Tibbetts, J. C., "Clint Eastwood and the Machinery of Violence," in Literature-Film Quarterly , vol. 21, no. 1, 1993.

Biskind, Peter, "Any Which Way He Can," in Premiere (New York), April 1993.

Grenier, Richard, "Clint Eastwood Goes PC," in Commentary , March 1994.

Beard, William, " Unforgiven and the Uncertainties of the Heroic," in Canadian Journal of Film Studies (Ottawa), vol. 3, no. 2, Autumn 1994.

Welsh, James M., "Fixing the Bridges of Madison County," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), July 1995.

Schickel, Richard, Cathleen Murphy, and Richard Combs, "Clint on the Back Nine/ The Good, the Bad & the Ugly /Old Ghosts," in Film Comment (New York), May-June 1996.

Burdeau, Emmanuel, "Physique des auteurs," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July-August 1996.

Greene, R., "Power and the Glory," in Boxoffice (Chicago), January 1997.

Metz, Walter, "'Another Being We Have Created Called "Us"': Point of View, Melancholia, and the Joking Unconscious in The Bridges of Madison County ," in Velvet Light Trap (Austin, Texas), Spring 1997.

Axelrad, Catherine, and Michel Cieutat, "Clint Eastwood," in Positif (Paris), June 1997.

McReynolds, Douglas J., "Alive and Well: Western Myth in Western Movies," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), January 1998.

Plantinga, Carl, "Spectacles of Death: Clint Eastwood and Violence in Unforgiven ," in Cinema Journal (Austin, Texas), Winter 1998.

* * *

In 1992, after almost forty years in the business, Clint Eastwood finally received Oscar recognition. Unforgiven brought him the awards for Best Achievement in Directing and for Best Picture, along with a nomination for Best Actor. Indeed, this strikingly powerful Western was nominated for no less than nine Academy Awards, Gene Hackman collecting Best Supporting Actor for his performance as the movie's ruthless marshall, "Little Bill" Daggett, and Joel Cox taking the Oscar for editing. It seems appropriate, therefore, that this film, which brought him such recognition, should end with the inscription "Dedicated to Sergio and Don." For without the intervention and influence of his two "mentors," directors Sergio Leone and Don Siegel, it is difficult to imagine Eastwood achieving his present respectability, let alone emerging as the only major star of the modern era who has become a better director than he ever was an actor.

That is not to belittle Eastwood, who has always been generous in crediting Leone and Siegel, and who is certainly far more than a passive inheritor of their directorial visions. Even in his Rawhide days of the 1950s and early 1960s he wanted to direct; more than once Eastwood has told of his attempts to persuade that series' producers to let him shoot some of the action rather more ambitiously than was the TV norm. Not surprisingly, they were reluctant, but they did in the end allow him to make trailers for upcoming episodes. He was not to take on a full-fledged directorial challenge until 1971 and Play Misty for Me , but in the intervening years he had become a massive boxoffice attraction as an actor, first with Leone in Europe in the three famous and founding "spaghetti westerns," and then in a series of films with Siegel back in the United States, most significantly Dirty Harry. It is not easy to untangle the respective influences of his mentors. In general terms, because they both contributed to the formation of Eastwood's distinctive screen persona, they helped him to crystallize an image which, as a director, he would so often use as a foil. The Italian Westerns' "man with no name," and his more anguished urban equivalent given expression in Dirty Harry 's eponymous anti-hero, have provided Eastwood with well-established and economical starting characters for so many of his performances. In directing himself, furthermore, he has used that persona with a degree of irony and distance. Sometimes, especially in his Westerns, that has meant leaning toward stylization and almost operatic exaggeration ( High Plains Drifter , Pale Rider , the last section of Unforgiven ), though rarely reaching Leone's extremes of delirious overstatement. On other occasions, it has seen him play on the tension between the seemingly assertive masculinity of the Eastwood image and the strong female characters who are so often featured in his films ( Play Misty for Me , The Gauntlet , Heartbreak Ridge and, in part at least, The Bridges of Madison County ). It is, of course, notoriously difficult to both direct and star in a movie. Where Eastwood has succeeded in that combination (not always the case) it has depended significantly on his inventive building on the Eastwood persona.

It is important to give Eastwood full credit for this inventiveness in any attempt to assess his work. His best films as a director have a richness to them, not just stylistically—though in those respects he has learned well from Leone's concern with lighting and composition and from Siegel's way with in-frame movement, editing, and tight narration—but also a moral complexity which belies the onedimensionality of the Eastwood image. The protagonists in his better films, like Josey Wales in The Outlaw Josey Wales , Highway in Heartbreak Ridge , Munny in Unforgiven , even Charlie Parker in the flawed Bird , are not simple men in either their virtues or their failings. Eastwood's fondness for narratives of revenge and redemption, furthermore, allows him to draw upon a rich generic vein in American cinema, a tradition with a built-in potential for character development and for evoking human complexity without giving way to art-film portentousness.

In these respects Eastwood is the modern inheritor of traditional Hollywood directorial values, once epitomised in the transparent style of a John Ford, Howard Hawks, or John Huston (himself the subject of Eastwood's White Hunter, Black Heart ), and passed on to Eastwood by that next-generation carrier of the tradition, Don Siegel. For these filmmakers, as for Eastwood, the action movie, the Western, the thriller were opportunities to explore character, motivation, and human frailty within a framework of accessible entertainment. Of course, all of them were also capable of "quieter" films, harnessing the same commitment to craft, the same attention to detail, in the service of less action-driven narratives, just as Eastwood did with The Bridges of Madison County. And all of them, too, could make films which were less than convincing, though rarely without some quality, as Eastwood has done more recently with the overwrought Absolute Power and the rather unfocused Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. But in the end their and Eastwood's real art was to draw upon Hollywood's genre traditions and make of them unique and perceptive studies of human beings under stress. Though his directorial career has been uneven, at his best Eastwood has proved a more than worthy carrier of this flame.

—Andrew Tudor

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: