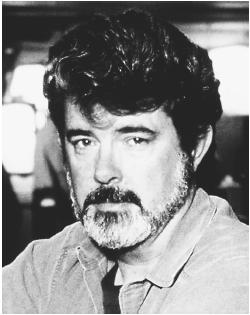

George Lucas - Director

Nationality: American. Born: George Walton Lucas Jr., Modesto, California, 14 May 1944. Education: Attended Modesto Junior College; University of Southern California Film School, graduated 1966. Career: Six-month internship at Warner Bros. spent as assistant to Francis Ford Coppola, 1967–68; co-founder, with Coppola, American Zoetrope, Northern California, 1969; directed first feature,

THX-1138 , 1971; established special effects company, Industrial Light and Magic, at San Rafael, California, 1976; formed production company Lucasfilm, Ltd., 1979; founded post production company Sprocket Systems, 1980; built Skywalker Ranch, then executive producer for Disneyland's 3-D music space adventure, Captain EO , 1980s. Awards: Locarno International Film Festival Bronze Leopard Award, and National Society of Film Critics Awards, U.S.A., NSFC Award for Best Screenplay, and New York Film Critics Circle Awards, NYFCC Award for Best Screenplay (with Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck) for American Graffiti , 1973; ShoWest Convention Showest Award for Director of the Year, 1978; Academy Awards Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, 1992. Address: c/o Lucasfilm, Ltd., P.O. Box 2009, San Rafael, California 94912, U.S.A.

Films as Director and Scriptwriter:

(Short student films)

- 1965–67

-

Look at Life ; Freiheit ; 1.42.08 ; Herbie (co-d); Anyone Lived in a Pretty How Town (co-sc); 6.18.67 (doc); The Emperor (doc); THX 1138:4EB

- 1968

-

Filmmaker (doc)

(Feature films)

- 1971

-

THX 1138 (co-sc, ed)

- 1973

-

American Graffiti (co-sc)

- 1977

-

Star Wars (+ exec pr)

- 1999

-

Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (+sc, exec pr)

- 2002

-

Star Wars: Episode II (+sc, exec pr)

- 2005

-

Star Wars: Episode III (+sc, pr)

Films as Executive Producer:

- 1979

-

More American Graffiti (Norton) (+ story)

- 1980

-

The Empire Strikes Back (Kershner) (+ story); Kagemusha ( The Shadow Warrior ) (Kurosawa) (of int'l version)

- 1981

-

Raiders of the Lost Ark (Spielberg) (+ story); Body Heat (Kasdan) (uncredited)

- 1982

-

Twice upon a Time (Korty and Swenson)

- 1983

-

Return of the Jedi (Marquand) (+ co-sc, story)

- 1984

-

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (Spielberg) (+ story)

- 1985

-

Mishima (Schrader)

- 1986

-

Howard the Duck (Huyck); Labyrinth (Henson); Captain EO (Coppola) (+ sc)

- 1988

-

Willow (Howard) (+ story); Tucker: The Man and His Dream (Coppola); The Land before Time

- 1989

-

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (Spielberg) (+ story)

- 1994

-

Radioland Murders (Mel Smith) (+ story)

Publications

By LUCAS: books—

American Graffiti: A Screenplay , with Gloria Katz and Willard Stuyck, New York, 1973.

The Empire Strikes Back , New York, 1997.

The Art of "Star Wars": Episode VI—Return of the Jedi (with Laurence Kasdan), New York, 1997.

George Lucas: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers Series) , edited by Sally Kline, Mississippi, 1999.

Star Wars: A New Hope , New York, 1999.

Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace: Script Facsimile , Los Angeles, 2000.

By LUCAS: articles—

" THX-1138 ," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), October 1971.

"The Filming of American Graffiti ," an interview with L. Sturhahn, in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), March 1974.

Interview with S. Zito, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1977.

Interview with Robert Benayoun and Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), September 1977.

Interview with Audie Bock, in Take One (Montreal), no. 6, 1979.

Interview with M. Tuchman and A. Thompson, in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1981.

Interview with David Sheff, in Rolling Stone (New York), 5 November/10 December 1987.

Interview with Philippe Rouyer and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), October 1994.

"30 Minutes with the Godfather of Digital Camera," interview with Don Shay, in Cinefex (Riverside), March 1996.

"George Lucas: Past, Present, and Future," interview with Ron Magid, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1997.

"The Future Starts Here," in Premiere (New York), February 1999.

Interview with Anne Thompson, in Premiere (New York), May 1999.

On LUCAS: books—

Smith, Thomas G., Industrial Light and Magic: The Art of Special Effects , New York, 1986.

Champlin, Charles, George Lucas, The Creative Impulse: Lucasfilm's First Twenty Years , New York, 1992.

Carrau, Bob, Monsters and Aliens from George Lucas , New York, 1993.

Cotta Vaz, Mark, and Shinji Hata, From Star Wars to Indiana Jones: The Best of Lucasfilm Archives , San Francisco, 1994.

Baxter, John, Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas , Shaker Heights, 1998.

White, Dana, George Lucas , Toronto, 1999.

Pollock, Dale, Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas , New York, 1999.

On LUCAS: articles—

Farber, Steven, "George Lucas: The Stinky Kid Hits the Big Time," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1974.

"Behind the Scenes of Star Wars ," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), July 1977.

Fairchild, B. H., Jr., "Songs of Innocence and Experience: The Blakean Vision of George Lucas," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), no. 2, 1979.

Pye, Michael, and Lynda Myles, "The Man Who Made Star Wars ," in Atlantic Monthly (Greenwich, Connecticut), March 1979.

Harmetz, A., "Burden of Dreams: George Lucas," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), June 1983.

Garsault, A., "Les paradoxes de George Lucas," in Positif (Paris), September 1983.

Schembri, J., "Robert Watts: Spielberg, Lucas and the Temple of Doom," in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), October/November 1984.

"George Lucas," in Film Dope (London), February 1987.

Star Wars Section of Variety (New York), 3 June 1987.

Kearney, J., and J. Greenberg, "The Road Warrior," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), June 1988.

Kaplan, David A., "The Force of an Idea Is with Him," in Newsweek , 31 May 1993.

Marx, Andy, "The Force Is with Him: Star Wars Savant Lucas Plans Celluloid," in Variety , 4 October 1993.

Marx, Andy, "Lucas Dishes Future Media at Intermedia," in Variety , 7 March 1994.

King, Thomas, "Lucasvision," in Wall Street Journal , March 1994.

Weintraub, Bernard, "The Ultimate Hollywoodian Lives an Anti-Hollywood Life," in New York Times , 20 October 1994.

Biskind, Peter, "'Radio' Days," in Premiere , November 1994.

Weiner, Rex, "Lucas the Loner Returns to 'Wars'," in Variety , 5 June 1995.

Groves, M., "Digital Yoda," in Los Angeles Times , June 1995.

Scorsese, Martin, "Notre génération," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1996.

Kaplan, D.A., "The Force Is Still with Him," in Newsweek , 13 May 1996.

Payne, M., " Return of the Jedi ," in Boxoffice (Chicago), November 1996.

Uram, S., "Use the Force, Lucas," in Cinefantastique (Forest Park), no. 6, 1996.

Seabrook, J., "Why Is the Force Still with Us?" in New Yorker , 6 January 1997.

Lev, Peter, "Whose Future? Star Wars, Alien, and Blade Runner ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), January 1998.

"How George Did It," in Written By. Journal: The Writers Guild of America, West (Los Angeles), December/January 1998.

McCarthy, Todd, "Mighty Effects but Mini Magic," in Variety (New York), 17 May 1999.

Daly, Steve, "The Star Report," in Entertainment Weekly (New York), 21 May 1999.

* * *

In whatever capacity George Lucas works—director, writer, producer—the films in which he is involved are a mixture of the familiar and the fantastic. Thematically, Lucas's work is often familiar, but the presentation of the material usually carries his unique mark. His earliest commercial science-fiction film, THX 1138 , is not very different in plot from previous stories of futuristic totalitarian societies in which humans are subordinate to technology. What is distinctive about the film is its visual impact. The extreme close-ups, bleak sets, and crowds of "properly sedated" shaven-headed people moving mechanically through hallways effectively produce the physical environment of this cold, well-ordered society. The endless whiteness of the vast detention center without bars could not be more oppressive.

Although not a special effects film, American Graffiti , Lucas's second feature, does show his attention to detail and his interest in archetypal themes. Within the 24-hour period of the film, the heroic potential is brought forth from within the main characters, either through courageous action or the making of courageous decisions. The film captures America on the verge of transition from the 1950s to the brave new world of the 1960s. Lucas does this visually by recreating the 1950s on screen down to the smallest detail, but he also communicates through his characters the feeling that their lives will never be the same again.

The combination of convention, archetype, and fantasy comes together fully in Lucas's subsequent films—the Star Wars and Indiana Jones series. On one level the Star Wars saga is a fairy tale set in outer space, as suggested in the opening title: "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. . . ." The basic plot conventions of the fairy tale are present: a princess in distress, a powerful evil ruler, and courageous knights. The saga is also a tale of the emergence of the hero within and the quest by which individuals realize their true selves, for the princess is really a Shaman, the evil ruler a self divided in need of healing, and the knights latent heroes who do not realize themselves as such at the beginning of the tale.

Scenes, especially from Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back , look and sound like Flash Gordon episodes. Members of the Empire—the Emperor, Darth Vadar, the storm troopers—are an easily identifiable evil in their dark, drab clothing and cloaked or helmeted faces. Their movements are accompanied by a menacing, martial film score of the type that ushered Ming the Merciless on screen. Another reference that associates the Empire with a great evil is that the storm troopers in several scenes resemble the rows of assembled storm troopers on review in Triumph of the Will. In contrast to these images of darkness, the rebel forces and their habitats are colorful and full of life.

The Star Wars saga is also very much science fiction. The special effects developed to realize Lucas's futuristic vision brought about technological advances in motion picture photography. The workshop formed for the production of Star Wars , Industrial Light and Magic, continues on as an independent special effects production company. While working on Star Wars , John Dykstra developed the Dykstraflex camera, for which he received an Academy Award. The camera was used in conjunction with a computer to achieve the accuracy necessary in photographing multiple-exposure visual effects. Another advancement in motion-control photography was developed for The Empire Strikes Back —Brian Edlund's Empireflex camera.

Lucas and Steven Spielberg then set out to make a film based on the romantic action/adventure movies of the 1940s. The successful result was Raiders of the Lost Ark. Indiana Jones, based on the rough-edged, worldly wise screen heroes of those earlier adventure films, is set to such mythic tasks as the quest for the Ark of the Covenant and the quest for the Holy Grail. Jones's enemies on these quests (which occur in the first and the last films of the series), the Nazis, are representatives of the dark side of this universe and carry legendary status of their own. As in the Star Wars saga, the main characters, including the extraordinary Indiana, face challenges that will bring forth qualities and strengths they had not yet realized. The dialogue in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade especially emphasizes the theme of the hero within. At one point the senior Jones tells Indiana that "The search for the cup of Christ is the search for the divine in all of us"; later in the film Indiana is challenged to look within himself by the enemy as he is told, "It's time to ask yourself what you believe."

Radioland Murders is set in the world of live radio broadcasts of the late 1930s. All the conventional character types are here—from the inept director and his highly competent assistant to the golden-voiced booth announcer to the ever-creative sound-effects man. This romantic comedy/murder mystery was directed by Mel Smith, produced by Lucas, and based on an original story by Lucas. The narrative contains all the heroic challenges to spirit and character of more epic films condensed into a much smaller space and a much shorter time period. The action takes place within a few prime-time hours as a new radio network premieres. The broadcast carries on to a successful completion in spite of the murders of cast and crew, the police investigation, set breakdowns, and ego clashes. This universe of carefully contained chaos sometimes appears to be on the verge of spinning out of control, but it never does. The narrative, the broadcast, and the main characters persevere to the finish.

In 1999, Lucas returned to directing with the first film in the Star Wars saga, Episode I—The Phantom Menace , which he also scripted. The film contains all the Lucas hallmarks, but he was perhaps illadvised to take on the project himself. The prequel lacks much of the subtlety of Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope , the only other film in the sequence he has so far directed, and was nominated in 2000 for "Razzie" awards for Worst Direction and Worst Screenplay. Such is Lucas's following, however, that Phantom Menace became the third-highest grossing movie of all time, and Lucas has announced his intention to make at least two further episodes. The simple story of a conflict between good and evil (essentially left over from the classic Western) continues to be carried by impressive special effects, but it remains to be seen how long general audiences will remain satisfied by a moral structure indicated by the color of the protagonists' clothing.

Lucas's films are self-conscious about genre conventions and often refer back to earlier films. Also familiar in his work are the archetypal figures from myths and legends. At the same time, the films are fantastic and unfamiliar, filled with strange creatures and exotic settings. However, the narrative weaknesses of Phantom Menace suggest he is somewhat less adept with the processes of storytelling than with realizing ambitious action sequences and inventive special effects.

—Marie Saeli, updated by Chris Routledge

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: