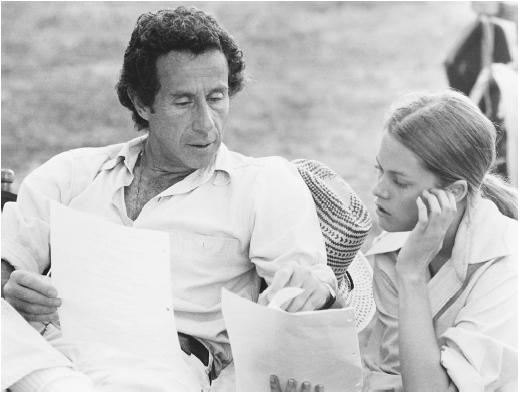

Arthur Penn - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Philadelphia, 27 September 1922.

Education:

Black Mountain College, North Carolina, 1947–48; studied at

Universities of Perugia and Florence, 1949–50; trained for the

stage with Michael Chekhov.

Military Service:

Enlisted in Army, 1943; joined Soldiers Show Company, Paris, 1945.

Family:

Married actress Peggy Maurer, 1955, one son, one daughter.

Career:

Assistant director on

The Colgate Comedy Hour

, 1951–52; TV director, from 1953, working on

Gulf Playhouse: 1st Person

(NBC),

Philco Television Playhouse

(NBC), and

Playhouse 90

(CBS); directed first feature,

The Left-handed Gun

, 1958; director on Broadway, from 1958.

Awards:

Tony Award for stage version of

The Miracle Worker;

two Sylvania Awards.

Address:

c/o 2 West 67th Street, New York, NY 10023, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1958

-

The Left-handed Gun

- 1962

-

The Miracle Worker

- 1965

-

Mickey One (+ pr)

- 1966

-

The Chase

- 1967

-

Bonnie and Clyde

- 1969

-

Alice's Restaurant (+ co-sc)

- 1970

-

Little Big Man (+ pr)

- 1973

-

"The Highest," in Visions of 8

- 1975

-

Night Moves

- 1976

-

The Missouri Breaks

- 1981

-

Four Friends

- 1985

-

Target

- 1987

-

Dead of Winter

- 1989

-

Penn and Teller Get Killed (+ pr)

- 1993

-

The Portrait (for TV)

- 1995

-

Lumière et compagnie

- 1996

-

Inside

Publications

By PENN: articles—

"Rencontre avec Arthur Penn," with André Labarthe and others, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), October 1965.

" Bonnie and Clyde : Private Morality and Public Violence," in Take One (Montreal), vol. 1, no. 6, 1967.

Interview with Michael Lindsay, in Cinema (Beverly Hills), vol. 5, no. 3, 1969.

Interview in The Director's Event by Eric Sherman and Martin Rubin, New York, 1970.

"Metaphor," an interview with Gordon Gow, in Films and Filming (London), July 1971.

"Arthur Penn at the Olympic Games," an interview in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), November 1972.

"Night Moves," an interview with T. Gallagher, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1975.

"Arthur Penn ou l'anti-genre," an interview with Claire Clouzot, in Ecran (Paris), December 1976.

Interview with R. Seidman and N. Leiber, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1981.

Interview with A. Leroux, in 24 Images (Montreal), June 1983.

Interview with Richard Combs, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), August 1986.

"1968–1988," in Film Comment (New York), August 1988.

"L'Amerique qui change: entretien avec Arthur Penn," with P. Merenghetti, in Jeune Cinema , October/November 1990.

"The Importance of a Singular, Guiding Vision," an interview with Gary Crowdus and Richard Porton, in Cineaste (New York), 1993.

"Acteurs et metteurs en scène: Metteurs en scène et acteurs," in Positif (Paris), June 1994.

"L'occhio aperto," an interview with G. Garlazzo, in Filmcritica (Siena), May 1997.

"Song of the Open Road," an interview with Geoffrey Macnab, in Sight and Sound (London), August 1999.

On PENN: books—

Wood, Robin, Arthur Penn , New York, 1969.

Marchesini, Mauro, and Gaetano Stucchi, Cinque film di Arthur Penn , Turin, 1972.

Cawelti, John, editor, Focus on Bonnie and Clyde , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1973.

Carlini, Fabio, Arthur Penn , Milan, 1977.

Kolker, Robert Phillip, A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Kubrick, Coppola, Scorsese, Altman , Oxford, 1980; revised edition, 1988.

Zuker, Joel S., Arthur Penn: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1980.

Giannetti, Louis D., Masters of the American Cinema , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1981.

Haustrate, Gaston, Arthur Penn , Paris, 1986.

Vernaglione, Paolo, Arthur Penn , Florence, 1988.

Kindem, Gorham, The Live Television Generation of Hollywood Film Directors , Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, 1994.

On PENN: articles—

Hillier, Jim, "Arthur Penn," in Screen (London), January/February 1969.

Gelmis, Joseph, "Arthur Penn," in The Film Director as Superstar , New York, 1970.

Wood, Robin, "Arthur Penn in Canada," in Movie (London), Winter 1970/71.

Margulies, Lee, "Filming the Olympics," in Action (Los Angeles), November/December 1972.

" Le Gaucher Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), November 1973.

Byron, Stuart, and Terry Curtis Fox, "What Is a Western?," in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1976.

Butler, T., "Arthur Penn: The Flight from Identity," in Movie (London), Winter 1978/79.

Penn Section of Casablanca (Madrid), March 1982.

"TV to Film: A History, a Map, and a Family Tree," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), February 1983.

Gallagher, J., and J. Hanc, "Penn's Westerns," in Films in Review (New York), August/September 1983.

Camy, G., "Arthur Penn: Un regard sévère sur les U.S.A. des années 60–70," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), April 1985.

Andrew, Geoff, " The Shootist ," in Time Out (London), 13 August 1986.

Matheson, Nigel, "Arthur Penn," in City Limits (London), 21 August 1986.

Richards, P., "Arthur Penn: A One-Film Director?" in Film , October 1987.

Knowles, Peter C., "Genre and Authorship: Two Films of Arthur Penn," in CineAction! (Toronto), Summer/Autumn 1990.

McCloy, Sean, "Focus on Arthur Penn," in Film West (Dublin), July 1995.

Kock, I. de, "Arthur Penn," in Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), November 1996.

Lally, K., "'Inside' with Arthur Penn," in Film Journal (New York), January/February 1997.

Elia, Maurice, "Bonnie and Clyde," in Séquences (Haute-Ville), July-August 1997.

* * *

Arthur Penn has often been classed—along with Robert Altman, Bob Rafelson, and Francis Coppola—among the more "European" American directors. Stylistically, this is true enough. Penn's films, especially after Bonnie and Clyde , tend to be technically experimental, and episodic in structure; their narrative line is elliptical, under-mining audience expectations with abrupt shifts in mood and rhythm. Such features can be traced to the influence of the French New Wave, in particular the early films of François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, which Penn greatly admired.

In terms of his thematic preoccupations, though, few directors are more utterly American. Repeatedly, throughout his work, Penn has been concerned with questioning and re-assessing the myths of his country. His films reveal a passionate, ironic, intense involvement with the American experience, and can be seen as an illuminating chart of the country's moral condition over the past thirty years. Mickey One is dark with the unfocused guilt and paranoia of the McCarthyite hangover, while the stunned horror of the Kennedy assassination reverberates through The Chase. The exhilaration, and the fatal flaws, of the 1960s anti-authoritarian revolt are reflected in Bonnie and Clyde and Alice's Restaurant. Little Big Man reworks the trauma of Vietnam, while Night Moves is steeped in the disillusioned malaise that pervaded the Watergate era.

As a focus for his perspective on America, Penn often chooses an outsider group and its relationship with mainstream society. The Indians in Little Big Man , the Barrow Gang in Bonnie and Clyde , the rustlers in The Missouri Breaks , the hippies in Alice's Restaurant , the outlaws in The Left-handed Gun , are all sympathetically presented as attractive and vital figures, preferable in many ways to the conventional society which rejects them. But ultimately they suffer defeat, being infected by the flawed values of that same society. "A society," Penn has commented, "has its mirror in its outcasts."

An exceptionally intense, immediate physicality distinguishes Penn's work. Pain, in his films, unmistakably hurts , and tactile sensations are vividly communicated. Often, characters are conveyed primarily through their bodily actions: how they move, walk, hold themselves, or use their hands. Violence is a recurrent feature of his films—notably in The Chase, Bonnie and Clyde , and The Missouri Breaks —but it is seldom gratuitously introduced, and represents, in Penn's view, a deeply rooted element in the American character which has to be acknowledged.

Penn established his reputation as a director with Bonnie and Clyde , one of the most significant and influential films of its decade. But since 1970 he has made only a handful of films, none of them successful at the box office. Night Moves and The Missouri Breaks , both poorly received on initial release, now rank among his most subtle and intriguing movies, and Four Friends , though uneven, remains constantly stimulating with its oblique, elliptical narrative structure.

But since then Penn seems to have lost his way. Neither Target , a routine spy thriller, nor Dead of Winter , a reworking of Joseph H. Lewis's cult B-movie My Name Is Julia Ross , offered material worthy of his distinctive talents. Penn and Teller Get Killed , a spoof psycho-killer vehicle for the bad-taste illusionist team, got few showings outside the festival circuit. Among his few recent directorial works is The Portrait , a solidly crafted adaptation for television of Tina Rowe's Broadway hit, Painting Churches. "It's not that I've drifted away from film," Penn told Richard Combs in 1986. "I'm very drawn to film, but I'm not sure that film is drawn to me." Given the range, vitality, and sheer unpredictability of his earlier work, the estrangement is much to be regretted.

—Philip Kemp