Man Ray - Director

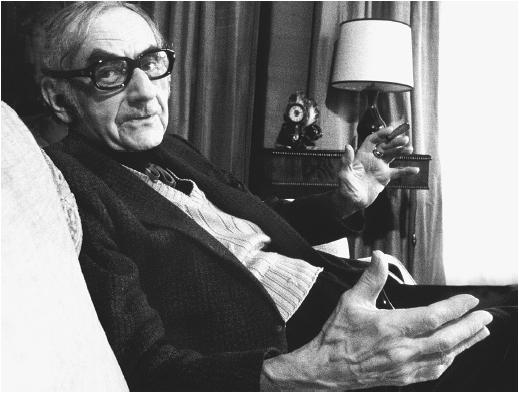

Nationality: American. Born: Emanuel Rabinovitch, Philadelphia, PA, 27 August 1890. Family: Married Adon Lacroix, 1913 (divorced 1920); married Juliet Browning, 1946. Education: Studied art, architecture, and engineering at the National Academy of Design, the Art Student's League and the Ferrer Center in New York City. Career: 1911—taught at Ferrer Center in New York; 1913—one-man show at the Daniel Gallery in New York;1915—met artist Marcel Duchamp and helped form the New York Dada group; 1916—begins to experiment with photography; 1921—departs for Paris, discovers rayographs (photographs made by leaving objects on photographic paper, and has one-man exhibition at the "exposition Dada"; 1923—makes first film, La Retour à la raison ( Return to Reason ); 1929—rediscovers solarization (rendering a photographic image part negative, part positive by exposing a print or negative to white light); 1940—returns to the United States (Hollywood) to escape the German occupation; 1944—gives a retrospective exhibition at the Pasadena Art Institute; 1950—returns to Paris; 1963—publishes his autobiography ( Self-Portrait ). Died: Paris, France, 18 November 1976.

Films as Director:

- 1924

-

Le Retour à la raison ( Return to Reason ) (+ed, + pr); À quoi rêvent les jeunes films ( What Do Young Films Dream About? )

- 1926

-

Emak-Bakia (+ph)

- 1928

-

L'Étoile de mer ( Starfish ) (+ph, pr)

- 1929

-

Les Mystères du château de Dé ( The Mysteries of the Chateau de De ) (+ph)

- 1935

-

Essai de simulation de délire cinématographique ( Attempt at Simulating Cinematographic Delirium )

- 1941

-

Dreams That Money Can Buy

Other Films:

- 1924

-

Entr'acte ( Intermission ) (Clair, Picabia) (as Man Ray); Ballet mécanique ( Mechanical Ballet ) (Léger, Murphy) (ph)

- 1926

-

Anémic cinéma ( Anemic Cinema ) (Duchamp) (ph, asst)

Publications

By RAY: books—

Self-Portrait , R. Laffont, 1964.

Man Ray , Aperture, 1973.

On RAY: books—

Belz, Carl, The Role of Man Ray in the Dada and Surrealist Movements , Princeton, 1963.

Penrose, Roland, Sir, Man Ray , Thames and Hudson, 1975.

Schwarz, Arturo, The Rigour of Imagination , Rizzoli, 1977.

Esten, John, Man Ray: Bazaar Years , Rizzoli, 1988.

On RAY: articles—

Foresta, Merry, "Tracing the Line," Aperture (San Francisco), Fall 1991.

Hopkins, David, "Men before the Mirror," Art History (London), September 1998.

Boxer, Sarah, "Surreal, but Not Taking Chances," New York Times , 20 November 1998.

Goldberg, Vicki, "Get a Great Image," New York Times , 5 Febru-ary 1999.

* * *

In 1924, Man Ray, already a renowned painter, photographer, and participant in the Dada movement, began to experiment with the medium of film. At the time Man Ray was in the company of many of his avant-garde comrades, including Marcel Duchamp, René Clair, and Fernand Léger. Under the influence of the avant-garde ideals, Ray and his friends began concentrated on the technical potential of film-making, the possibilities of special effects, cinematic distortion, slow motion, etc., and abandoned the quest for narrative. The effect of this experimentation can be seen in many of Ray's films.

Ray's first project combined techniques he had cultivated in still photography and the experimental cinematic techniques developed by the avant-garde. This project , Le Retour à la raison ( The Return to Reason ), was completed in 1923. This film is literally a collection of Ray's special photographs, or rayographs, strung together to form several series of images. Here, as in Ray's later films, the emphasis is not on telling a story. Rather, it is to play with the possibility of representing light, shape, and movement on film.

Ray's second film effort came in 1924 and was a collaborative project with his close friend, Marcel Duchamp. Anémic cinéma ( Anemic Cinema ) for which Ray functioned as cinematographer, is yet another experiment with the possibilities of cinema. The film features a set of spiraling disks, on which are placed French words. Through movement and camera focus, the words combine to form phrases and puns in French. Here again, there is no narrative. Instead, there is an emphasis on the non-sense of language and on the nonsense of art, both of which formed the basis of the Dada movement.

In the second half of the 1920s, Ray made three films that he characterized as cinematic poetry. These films, Emak-Bakia , L'Étoile de mer ( The Starfish ), and Les Mystères du château de Dé ( The Mysteries of the Chateau de De ), were made to cause the viewer to "rush out and breath the pure of the outside, be the leading actor and solve his own dramatic problems." In that way, Ray affirmed, the spectator realizes "a long cherished dream of becoming a poet, an artist himself." As revealed by Ray's comments, this is a participatory cinema, where the spectator is expected to form meaning from his own unique viewing experience.

Emak-Bakia is in part a continuation of the technique introduced in Le Retour à la raison in that it, too, includes a series of rayographs. This film, however, is more sophisticated in a technical sense than the first, employing rapid cutting, superimposition and slow motion to create a far more complex, though equally abstract film. In addition, Ray also incorporates a great deal more play with light in the film, even inserting non-objective reflections into the body of the film. In addition to these purely abstract images, Ray interposes realistic images of daily objects, people and landscapes. The result is a highly visual study of motion, shape, and light, that reveals a methodical experimentation with the possibilities of representing such phenomena.

L'Étoile de mer ( The Starfish ), perhaps Ray's masterpiece, is literally a poem on film. Based on an unpublished poem by Surrealist poet Robert Desnos, the film is an attempt to represent verbal poetry as visual spectacle. Unlike his earlier films, L'Étoile de mer is constructed of realistic images rather than pure shapes or light forms, and yet it is equally non-narrative and equally abstract. In the film, sequences of couples meeting, undressing, getting into bed, parting, are shown in alternation with images of static objects, fields, the sea, a street. Thus, the frenzy and fervor of the human being's movement toward sexual contact is juxtaposed against the sterility and stasis of everyday life. As in his preceding film, Ray experiments with light, with the camera and with representation in the film, using such techniques as extreme close-up, distortion and soft-focus, all used in contrast with a clear-focus lens.

Ray's third film from this period, Les Mystères du château de Dé ( The Mysteries of the Chateau de De ) shows a further development in the focus on real or realistic images in abstract cinema. Like L'Étoile de mer , this film relies heavily on sequences of human beings. Furthermore, of Ray's films, this one is the closest to being narrative, in that the sequences of images presented in the film seem, on the surface, to form a coherent whole. The film shows the voyage of a couple in a bar, who drive a great distance, arrive at a villa, and interact with other people. A great deal of attention is given to the house and to the actions engaged in by those staying there, and for a time, all seems "normal." Progressively, however, distortions in the size of objects, in the light and shadows of the background, in the characters' movements all become apparent. In the end, none of these distortions are "explained" by the film, nor is there a sense given to the actions of the characters. Despite its more narrative appearance , Les Mystères du château de Dé remains as abstract as Ray's earlier films. Furthermore, the influence of the Surrealist movement can be seen very clearly in the seemingly banal images, which present unexplained and eerie irregularities.

By the late 1930s and 1940s, Ray had all but abandoned film to return to his two original passions, painting and still photography. Before his death, in 1976, he made only two more films , Essai de simulation de délire cinématographique ( Attempt at the Simulation of Cinematographic Delirium ) from 1935, and Dreams That Money Can Buy , in collaboration with Hans Richter, and many of his Dada-Surrealist collaborators. The first is highly reminiscent of Ray's films from the 1920s, and the second is a combination of more developed cinematographic techniques and embodies the spirit of the Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist movements. In fact, it is puzzling that in the very years that Ray was the closest to the film industry (he was living in Hollywood), he was the least interested in cinema.

Carl Belz has suggested that Man Ray withdrew from cinema partly because he felt he had exhausted its potential, and partly because it took him away from painting and photography. And it is, in fact, for his contributions to the latter that he is best remembered. Nonetheless, to overlook the impact of May Ray on the cinema is to ignore the influence of one of the early pioneers of cinematic art. It was Man Ray, and many of his Dada and Surrealist contemporaries who first drew attention to a great many of the cinematic techniques widely used today. For this, and for the fascinating efforts at producing a non-narrative cinema, Man Ray's films remain crucial to any understanding of the development of film.

—Dayna Oscherwitz

Candy Kemp, artist and writer.