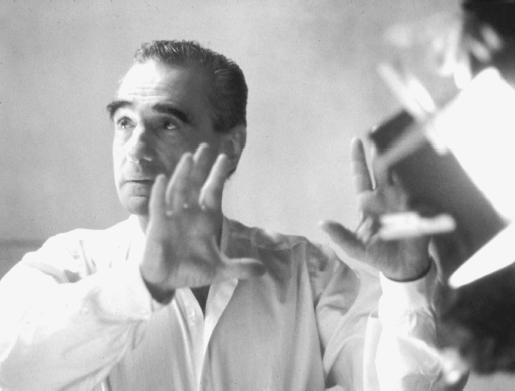

Martin Scorsese - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Flushing, New York, 17 November 1942. Education: Cardinal Hayes High School, Bronx, 1956–60; New York University, B.A., 1964, M.A., 1966. Family: Married 1) Laraine Brennan, 1965 (divorced), one daughter; 2) Julia Cameron (divorced), one daughter; 3) Isabella Rossellini, 1979 (divorced 1983); 4) Barbara DeFina, 1985. Career: Film Instructor, NYU, 1968–70; directed TV commercials in England, and first feature, Who's That Knocking at My Door? , 1968; directed Boxcar Bertha for producer Roger Corman, 1972; directed The Act on Broadway, 1977; director for TV of "Mirror, Mirror" for Amazing Stories , 1985; directed promo video for Michael Jackson's "Bad," 1987. Awards: Best Director, National Society of Film Critics, and Palme d'Or, Cannes Festival, for Taxi Driver , 1976; Best Director, National Society of Film Critics, for Raging Bull , 1980; Best Director, Cannes Festival, for The Color of Money , 1986; Best Director, National Society of Film Critics, for GoodFellas , 1990.

Films as Director:

- 1963

-

What's a Nice Girl like You Doing in a Place like This? (short) (+ sc)

- 1964

-

It's Not Just You, Murray (short) (+ co-sc)

- 1967

-

The Big Shave (short) (+ sc)

- 1968

-

Who's That Knocking at My Door? (+ sc, role as gangster)

- 1970

-

Street Scenes (doc)

- 1972

-

Boxcar Bertha (+ role as client of bordello)

- 1973

-

Mean Streets (+ co-sc, role as Shorty the Hit Man)

- 1974

-

Italian-American (doc) (+ co-sc)

- 1975

-

Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (+ role as customer at Mel and Ruby's)

- 1976

-

Taxi Driver (+ role as passenger)

- 1977

-

New York, New York

- 1978

-

The Last Waltz (doc)

- 1979

-

American Boy (doc) (+ sc)

- 1980

-

Raging Bull

- 1983

-

The King of Comedy (+ role as assistant)

- 1985

-

After Hours (+ role as disco patron)

- 1986

-

The Color of Money

- 1988

-

The Last Temptation of Christ

- 1989

-

"Life Lessons" episode in New York Stories

- 1990

-

GoodFellas (+ sc); Man in Milan (doc)

- 1991

-

Cape Fear

- 1993

-

Age of Innocence (+ sc, role)

- 1995

-

Casino (+ sc)

- 1997

-

Kundun

- 1999

-

Bringing out the Dead ; Il Dolce Cinema (+ sc)

- 2001

-

The Gangs of New York

- 2002

-

Dino

Other Films:

- 1965

-

Bring on the Dancing Girls (sc)

- 1967

-

I Call First (sc)

- 1970

-

Woodstock (ed, asst d)

- 1976

-

Cannonball (Bartel) (role)

- 1979

-

Hollywood's Wild Angel (Blackwood) (role); Medicine Ball Caravan (assoc pr, post prod spvr)

- 1981

-

Triple Play (role)

- 1982

-

Bonjour Mr. Lewis (Benayoun) (role)

- 1990

-

Dreams (Kurosawa) (role); The Grifters (Frears) (pr); Fear No Evil (Winkler) (role); The Crew (Antonioni) (exec pr); Mad Dog and Glory (McNaughton) (exec pr)

- 1991

-

Guilty by Suspicion (role as Joe Lesser)

- 1993

-

Jonas in the Desert (role)

- 1994

-

Quiz Show (Redford) (role as sponsor); Naked in New York (exec pr)

- 1995

-

Search and Destroy (exec pr, role as accountant); Clockers (Lee) (pr)

Publications

By SCORSESE: books—

Scorsese on Scorsese , edited by Ian Christie and David Thompson, London, 1989.

Goodfellas , with Nicholas Pileggi, London, 1990.

The Age of Innocence: A Portrait of the Film Based on the Novel by Edith Wharton , New York, 1993.

A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies , with Michael Henry Wilson, British Film Institute, 1997.

By SCORSESE: articles—

"The Filming of Mean Streets ," an interview with A.C. Bobrow, in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), January 1974.

Interview with M. Carducci, in Millimeter (New York), vol. 3, no. 5, 1975.

Interview with M. Rosen, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1975.

Martin Scorsese Seminar, in Dialogue on Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1975.

"Scorsese on Taxi Driver and Herrmann," an interview with C. Amata, in Focus on Film (London), Summer/Autumn 1976.

Interview with Jonathan Kaplan, in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1977.

Interview with Richard Combs and Louise Sweet, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1977/78.

"Martin Scorsese's Guilty Pleasures," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1978.

Interview with Paul Schrader, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1982.

Interview with B. Krohn, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1986.

"Body and Blood," an interview with Richard Corliss, in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), vol. 24, no. 5, 1988.

Interview with Chris Hodenfield, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), March 1989.

"Entretien avec Martin Scorsese," with H. Niogret, in Positif (Paris), October 1990.

"Scorsese sur Scorsese," an interview with P. Rollet and others, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), October 1990.

Interview with A. Decurtis, in Rolling Stone (New York), November 1, 1990.

"Martin Scorsese: Gangster and Priest," an interview with A. M. Bahiana, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), December 1990.

Interview with David Rensin, in Playboy (Chicago, Illinois), April 1991.

Interviews with Graham Fuller, in Interview (New York), November 1991 and October 1993.

"Martin Scorsese's Mortal Sins," an interview with Marcelle Clements, in Esquire (New York), November 1993.

Interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment (New York), November/December 1993.

"A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies," an interview with Nicolas Saada, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), June 1995.

"Ace in the Hole: Visualizing a Vintage Vegas," an interview with Stephen Pizzello and Ron Magid, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), November 1995.

"Martin Scorsese's Testament: Bright Lights Big City," an interview with Ian Christie and Pat Kirkham, in Sight and Sound (London), January 1996.

Interview, in the Special Issue of Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1996.

Interview with Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), March 1996.

"Martin Scorsese's Calling: To Protect and Preserve Film Artists' Rights," an interview with Ted Elrick, in DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), March-April 1996.

"The Art of Vision: Martin Scorsese's Kundun ," an interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment (New York), January-February 1998.

An interview with Hubert Niogret and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), May 1998.

On SCORSESE: books—

Kolker, Robert Phillip, A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Kubrick, Coppola, Scorsese, Altman , Oxford, 1980; revised edition, 1988.

Bliss, Michael, Martin Scorsese and Michael Cimino , Metuchen, New Jersey, 1986.

Arnold, Frank, and others, Martin Scorsese , Munich, 1986.

Cietat, Michel, Martin Scorsese , Paris, 1986.

Domecq, Jean-Philippe, Martin Scorsese: Un Rêve Italo-Américan , Renens, Switzerland, 1986.

Weiss, Ulli, Das Neue Hollywood: Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese , Munich, 1986.

Wood, Robin, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan , New York, 1986.

Weiss, Marian, Martin Scorsese: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1987.

Kelly, Mary P., Martin Scorsese: A Journey , New York, 1991.

Ehrenstein, David, The Scorsese Picture: The Art and Life of Martin Scorsese , New York, 1992.

Keyser, Lester J., Martin Scorsese , New York, 1992.

Connelly, Marie K., Martin Scorsese: An Analysis of His Feature Films , Jefferson, North Carolina, 1993.

Friedman, Lawrence S., The Cinema of Martin Scorsese , New York, 1998.

On SCORSESE: articles—

Gardner, P. "Martin Scorsese," in Action (Los Angeles), May/June 1975.

Scorsese Section of Positif (Paris), April 1980.

"Martin Scorsese vu par Michael Powell," in Positif (Paris), April 1981.

Rickey, C., "Marty," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), November 1982.

Rafferty, T., "Martin Scorsese's Still Life," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1983.

Braudy, Leo, "The Sacraments of Genre: Coppola, De Palma, Scorsese," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1986.

Bruce, B., "Martin Scorsese: Five Films," in Movie (London), Winter 1986.

"Scorsese Issue" of Film Comment (New York), September/October 1988.

Jenkins, Steve, "From the Pit of Hell," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), December 1988.

Williams, T., " The Last Temptation of Christ: A Fragmented Oedipal Trajectory," in CineAction (Toronto), Winter/Spring 1990.

Morgan, D., "The Thriller in Scorsese," in Millimeter (New York), October 1991.

Biskind, Peter, "Slouching toward Hollywood," in Premiere (New York), November 1991.

Stanley, A., "From the Mean Streets to Charm School," in New York Times , 28 June 1992.

Murphy, Kathleen, "Artist of the Beautiful," in Film Comment (New York), November/December 1993.

Schrader, Paul, "Paul Schrader on Martin Scorsese," in New Yorker , 21 March 1994.

Thurman, J., "Martin Scorsese's New York Story: An 1860s Town House for the Age of Innocence Director," in Architectural Digest (Los Angeles), April 1994.

Durgnat, Raymond, "Martin Scorsese: Between God and the Goodfellas," in Sight and Sound (London), June 1995.

Librach, Ronald S., "A Nice Little Irony: Life Lessons ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), April 1996.

Blake, Richard A., "Redeemed in Blood: The Sacramental Universe of Martin Scorsese," in Journal of Popular Film and Television (Washington, D.C.), Spring 1996.

Sherlock, James, "Why Thelma Loves Martin. . . and Michael," in Cinema Papers (Fitzroy), December 1996.

* * *

At present, with regard to the Hollywood cinema of the last fifteen years, two directors appear to stand head-and-shoulders above the rest, and it is possible to make large claims for their work on both formal and thematic grounds: Scorsese and Cimino. The work of each is strongly rooted in the American and Hollywood past, yet is at the same time audacious and innovative. Cimino's work can be read as at once the culmination of the Ford/Hawks tradition and a radical rethinking of its premises; Scorsese's involves an equally drastic rethinking of the Hollywood genres, either combining them in such a way as to foreground their contradictions (western and horror film in Taxi Driver ) or disconcertingly reversing the expectations they traditionally arouse (the musical in New York, New York , the boxing movie and "biopic" in Raging Bull ). Both directors have further disconcerted audiences and critics alike in their radical deviations from the principles of classical narrative: hence Heaven's Gate is received by the American critical establishment with blank incomprehension and self-defensive ridicule, while Scorsese has been accused (by Andrew Sarris, among others) of lacking a sense of structure. Hollywood films are not expected to be innovative, difficult, and challenging, and must suffer the consequences of authentic originality (as opposed to the latest in fashionable chic that often passes for it).

The Cimino/Scorsese parallel ends at this shared tension between tradition and innovation. While Heaven's Gate can be read as the answer to (and equal of) Birth of a Nation , Scorsese has never ventured into the vast fresco of American epic, preferring to explore relatively small, limited subjects (with the exception of The Last Temptation of Christ ), the wider significance of the films arising from the implications those subjects are made to reveal. He starts always from the concrete and specific—a character, a relationship: the vicissitudes in the careers and love-life of two musicians ( New York, New York ); the violent public and private life of a famous boxer ( Raging Bull ); the crazy aspirations of an obsessed nonentity ( King of Comedy ). In each case, the subject is remorselessly followed through to a point where it reveals and dramatizes the fundamental ideological tensions of our culture.

His early works are divided between self-confessedly personal works related to his own Italian-American background ( Who's That Knocking at My Door?, Mean Streets ) and genre movies ( Boxcar Bertha, Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore ). The distinction was never absolute, and the later films effectively collapse it, tending to take as their starting point not only a specific character but a specific star: Robert De Niro. The Scorsese/De Niro relationship has proved one of the most fruitful director/star collaborations in the history of the cinema; its ramifications are extremely complex. De Niro's star image is central to this, poised as it is on the borderline between "star" and "actor"—the charismatic personality, the self-effacing impersonator of diverse characters. It is this ambiguity in the De Niro star persona that makes possible the ambiguity in the actor/director relationship: the degree to which Scorsese identifies with the characters De Niro plays, versus the degree to which he distances himself from them. It is this tension (communicated very directly to the spectator) between identification and repudiation that gives the films their uniquely disturbing quality.

Indeed, Scorsese is perhaps the only Hollywood director of consequence who has succeeded in sustaining the radical critique of American culture that developed in the 1970s through the Reagan era of retrenchment and recuperation. Scorsese probes the tensions within and between individuals until they reveal their fundamental, cultural nature. Few films have chronicled so painfully and abrasively as New York, New York the impossibility of successful heterosexual relations within a culture built upon sexual inequality. The conflicts arising out of the man's constant need for self-assertion and domination and the woman's bewildered alterations between rebellion and complexity are—owing to the peculiarities of the director/star/character/spectator relationship—simultaneously experienced and analysed.

Raging Bull goes much further in penetrating to the root causes of masculine aggression and violence, linking socially approved violence in the ring to socially disapproved violence outside it, violence against men to violence against women. It carries to its extreme that reversal of generic expectations so characteristic of Scorsese's work: a boxing melodrama/success story, it is the ultimate anti- Rocky ; a filmed biography of a person still living, it flouts every unwritten rule of veneration for the protagonist, celebration of his achievements, triumph after tribulation, etc. Ostensibly an account of the life of Jake LaMotta, it amounts to a veritable case history of a paranoiac, and can perhaps only be fully understood through Freud. Most directly relevant to the film is Freud's assertion that every case of paranoia, without exception, has its roots in a repressed homosexual impulse; that the primary homosexual love-objects are likely to be father and brothers; that there are four "principle forms" of paranoia, each of which amounts to a denial of homosexual attraction (see the analysis of the Schreber case and its postscript). Raging Bull exemplifies all of this with startling (if perhaps largely inadvertent) thoroughness: all four of the "principle forms" are enacted in Scorsese's presentation of LaMotta, especially significant being the paranoid's projection of his repressed desires for men onto the woman he ostensibly loves. The film becomes nothing less than a statement about the disastrous consequences, for men and women alike, of the repression of bisexuality in our culture.

King of Comedy may seem at first sight a slighter work than its two predecessors, but its implications are no less radical and subversive: it is one of the most complete statements about the emotional and spiritual bankruptcy of patriarchal capitalism today that the cinema has given us. The symbolic Father (once incarnated in figures of mythic force, like Abraham Lincoln) is here revealed in his essential emptiness, loneliness, and inadequacy. The "children" (De Niro and Sandra Bernhard) behave in exemplary Oedipal fashion: he wants to be the father, she wants to screw the father. The film moves to twin climaxes. First, the father must be reduced to total impotence (to the point of actual immobility) in order to be loved; then Bernhard can croon to him "You're gonna love me/like nobody's loved me," and remove her clothes. Meanwhile, De Niro tapes his TV act which (exclusively concerned with childhood, his parents, self-depreciation) culminates in a joke about throwing up over his father's new shoes, the shoes he is (metaphorically) now standing in. We see ambivalence towards the father, the hatred-in-rivalry of "brother" and "sister," the son's need for paternal recognition (albeit in fantasy) before he can announce himself to the woman he (very dubiously) loves; and the irrelevance of the mother (a mere, intermittently intrusive, off-screen voice) to any "serious"—i.e., Oedipal patriarchal—concerns. Thus King of Comedy constitutes one of the most rigorous assaults we have on the structures of the patriarchal nuclear family and the impossible desires, fantasies, frustrations, and violence those structures generate: an assault, that is, on the fundamental premises of our culture.

Since 1990, Scorsese has made four films which, taken together, establish him definitively as the most important director currently working in Hollywood. GoodFellas, Cape Fear, The Age of Innocence , and Casino reveal an artist in total command of every aspect of his medium—narrative construction, mise-en-scène , editing, the direction of actors, set design, sound, music, etc. Obviously, he owes much to the faithful team he has built up over the years, each of whom deserves an individual appreciation; but there can be no doubt of Scorsese's overall control at every level, from the conceptual to the minutiae of execution, informed by his sense of the work as a totality to which every strand, every detail, contributes integrally. If the films continue to raise certain doubts, to prompt certain reservations, it is not on the level of realization, but on moral and philosophical grounds. Let it be said at once, however, that The Age of Innocence , which in advance seemed such an improbable project—provoking fears that it would not transcend the solid and worthy but fundamentally dull literary adaptations of James Ivory—is beyond all doubts and reservations a masterpiece of nuance and refinement, alive in its every moment.

The other three films all raise the much-debated issue of the presentation of violence. There seem to be two valid ways of presenting violence (as opposed to the violence as "fun" of Pulp Fiction , violence as "aestheticized ballet" of John Woo's films, or violence as "gross out" in the contemporary horror movie). One way is to refuse to show it, always locating it (by a movement of the camera or the actors) just off-screen (Lang in The Big Heat , Mizoguchi in Sansho Dayu) , leaving our imaginations free to experience its horror: a method almost totally absent from modern Hollywood. The other is to make it as explicit, ugly, painful, and disturbing as possible so that it becomes quite impossible for anyone other than an advanced criminal psychotic to enjoy it. The latter is Scorsese's method, and he cannot be faulted for it in the recent work. It was still possible, perhaps, to get a certain "kick" out of the violence in Taxi Driver , because of our ambiguous relationship to the central character, but this is no longer true of the violence in GoodFellas or Casino. An essential characteristic of the later films is the rigorous distance Scorsese constructs between the audience and all the characters: identification, if it can be said to exist at all, flickers only sporadically—is always swiftly contradicted or heavily qualified.

Yet herein lies what is at least a potential problem of these films. One can analyze the ways in which this distance is constructed, especially through the increasing fracturing of the narrative line, the splitting of voice-over narration among different characters in both GoodFellas and Casino; but isn't alienation, for many of us, inherent in the characters themselves and the subject matter? Scorsese has insisted that the characters of Casino are "human beings": fair enough. But he seems to imply that if we cannot feel sympathetic to them we are somehow assuming an unwarranted moral superiority. One might retort (to take an extreme case—but the Pesci character is already pretty extreme) that Hitler and Albert Schweitzer were both "human beings": may we not at least discriminate between them? One can feel a certain compassion for the characters (even Joe Pesci) as people caught up in a process they think they can control but which really controls them; but can one say more for them than that?

Beyond that, though connected with it, is the films' increasing inflation: not merely their length ( GoodFellas plays for almost twoand-a-half hours, Casino for almost three) but its accompanying sense of grandeur: for Scorsese, apparently, the grandeur of his subjects. One is invited to lament, respectively, the decline of the Mafia and of Las Vegas. But suppose one cannot see them, in the first place, in terms other than those of social disease? The films strike me as too insulated, too enclosed within their subjects and milieux: the Mafia and Las Vegas are never effectively "placed" in a wider social context. Scorsese's worst error seems to be the use in Casino of the final chorus from Bach's St. Matthew Passion: an error not merely of "tease" but of sense, comparable in its enormity to Cimino's use of the Mahler "Resurrection" symphony at the end of Year of the Dragon. If it is possible to lament the decline of Las Vegas, it surely cannot be inflated into the lament of Bach's cheer for the death of Christ on the cross.

One cannot doubt the authenticity of Scorsese's sense of the tragic. Yet it is difficult not to feel that he has not yet found for it (to adopt T. S. Eliot's famous formulation) an adequate "objective correlative."

Martin Scorsese began the 1990s on a high note with GoodFellas but as the decade progressed, he has lost the support of the critics and the public. Arguably, Scorsese hasn't tapered off as an artist; instead, the problem may be that his more recent films have failed to fulfill audience expectations. If so, it is somewhat ironic as Scorsese remains consistent in his thematic concerns and commitment to style as self expression.

Casino is admittedly a demanding film. Viewer identification isn't solicited and the film's violence is excessive but without the absurdist connotations found in GoodFellas . On the one hand, the film offers a portrait of the Robert De Niro character, a gambler who, through his connections with the Mafia, gets to manage a casino in Las Vegas during the late 1970s and early 1980s. But Casino is also an "epic" in that it reflects the growing power of corporations; realizing the money to be made, "respectable" business takes over Las Vegas. Not unlike his role in Raging Bull , De Niro's character succeeds ultimately to the extent that he survives. Scorsese's concern with surviving in a world that is violent, brutal, and overwhelmingly indifferent to the individual has been evident in his films from early on; but, in his more recent works, this concern is, if anything, treated with greater hesitation and delicacy.

Much has been made of Scorsese's Catholic background and its influence on his work. Kundun indicates that his interest in religion isn't confined to Christianity. Kundun can be taken as a companion piece to The Last Temptation of Christ ; but it can be considered equally in relation to Casino and the recent Bringing out the Dead . Like Casino , Kundun is an epic film; and its protagonist is also made to confront his fallibility and mortality. In Kundun , the Dalai Lama gradually achieves full consciousness of the destructiveness existing around him; the realization is what motivates him to accept the necessity of his survival. But unlike Casino , the violence in Kundun is constrained; it exists as a threat that fitfully and devastatingly erupts. Kundun is one of Scorsese's most stylized films. Consistent with his aesthetics, the film is a combination of expressionism and realism, with the former given precedence. Although the film doesn't directly impose viewer identification with the Dalai Lama, Kundun repeatedly features the Dalai Lama's subjective responses. In effect, the film manages to be a simultaneously distancing and intimate experience. With Bringing out the Dead , Scorsese and Paul Schrader collaborated on a project that evokes their seminal Taxi Driver . Like the earlier film, Bringing out the Dead takes place on New York's "mean streets" and features a male protagonist who, in addition to having a job which places him in direct contact with the city's seamy side, harbors a martyrdom complex and wants to obtain salvation through becoming a savior figure. Th crucial difference between the two films resides in the character of the protagonist. Unlike Taxi Driver 's Travis Bickle, the Nicolas Cage character in Bringing out the Dead is motivated by genuinely humanistic impulses. He wants, not unlike the Dalai Lama, to be a good person who is capable of actively preserving human life. The character undergoes a crisis regarding his worth; at the film's conclusion, he finds salvation through accepting his guilt over failure. As in Casino and Kundun , Bringing out the Dead is concerned fundamentally with the struggle between death and survival; and, like Casino , it is a brutal film. Although the film possesses an absurdist edge at times that suggests a black comedy, it is unrelenting in its capacity to disturb and horrify.

During the 1990s Scorsese produced works that have challenged the viewer as powerfully as any of his previous films. The films may have not found acceptance partly because his vision has become increasingly somber and elegiac. On the other hand, Scorsese refuses to despair and his films continue to be exhilarating and life affirming statements.

—Robin Wood, updated by Richard Lippe

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: