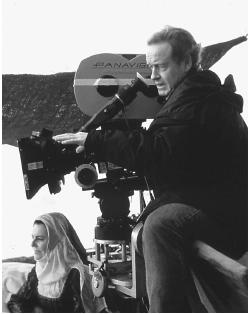

Ridley Scott - Director

Nationality: English. Born: South Shields, County Durham, 1939. Education: Studied at West Hartlepool College of Art and at the Royal College of Art, London. Family: Married, three children. Career: Set designer, then director for BBC TV, including episodes of Z-Cars and The Informer , 1966–67; set up production company Ridley Scott Associates, directed close to 3,000 commercials, from

Films as Director:

- 1977

-

The Duellists

- 1979

-

Alien

- 1982

-

Blade Runner

- 1985

-

Legend

- 1987

-

Someone to Watch over Me (+ exec-pr)

- 1989

-

Black Rain

- 1991

-

Thelma and Louise (+ co-pr)

- 1992

-

1492: The Conquest of Paradise (+ pr)

- 1996

-

White Squall (+ exec pr)

- 1997

-

G.I. Jane (+ pr)

- 2000

-

Gladiator

- 2001

-

Hannibal

Other Films:

- 1994

-

The Browning Version (co-pr); Monkey Business (exec pr)

- 1997

-

The Hunger (series for TV) (exec pr)

- 1998

-

Clay Pigeons (pr)

- 1999

-

RKO 281 (for TV) (pr)

Publications

By SCOTT: articles—

"Ridley Scott cinéaste du décor," an interview with O. Assayas and S. LePéron, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1982.

"Designer Genes," an interview with Harlan Kennedy, in Films (London), September 1982.

Interview with Hubert Niogret, in Positif (Paris), September 1985.

Interview with Sheila Johnston, in Films and Filming (London), November 1985.

Interview with Raphael Bassan and Raymond Lefevre, in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), February 1986.

Interview with M. Buckley, in Films in Review (New York), January 1987.

" Thelma and Louise Hit the Road for Ridley Scott," an interview with M. McDonagh, in Film Journal (New York), June 1991.

"Ridley Scott's Road Work," an interview with A. Taubin, in Sight and Sound (London), July 1991.

" 1492: Conquest of Paradise ," an interview with A. M. Bahiana, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), October 1992.

"Myth Revisited," an interview with M. Moss, in Boxoffice (Chicago), October 1992.

"Stormy Weather," an interview with David E. Williams, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1996.

Interview with A. Jones, in Cinema Papers (Fitzroy), July 1997.

On SCOTT: books—

Kernan, Judith B., ed., Retrofitting "Blade Runner": Issues in Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" and Philip K. Dick's "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, " Bowling Green, Ohio, 1991.

Sammon, Paul M., Ridley Scott: The Making of His Movies (Close Up) , New York, 1999.

On SCOTT: articles—

" Blade Runner Issue" of Cinefex (Riverside, California), July 1982.

" Blade Runner Issues" of Starburst (London), September/November 1982.

Kellner, Douglas, Flo Leibowitz, and Michael Ryan, " Blade Runner : A Diagnostic Critique," in Jump Cut (Chicago), no. 29, 1983.

Caron, A., "Les archétypes chez Ridley Scott," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), March 1983.

Durgnat, Raymond, "Art for Film's Sake," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), May 1983.

Milmo, Sean, "Ridley Scott Makes the Details Count," in Advertising Age (Chicago), 21 June 1984.

Doll, Susan, and Greg Faller, " Blade Runner and Genre: Film Noir and Science Fiction," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), no. 2, 1986.

Rosen, Barbara, "How the Man Who Made Alien Invaded Madison Avenue," in Business Week (New York), 24 March 1986.

Davis, Brian, "Ridley Scott: He Revolutionized TV Ads," in Adweek (Chicago), 2 October 1989.

Zimmer, J., "Ridley Scott," in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), September 1990.

"The Many Faces of Thelma and Louise " (8 short articles), in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1991/92.

Wilmington, Mike, "The Rain People," in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1992.

Wollen, Peter, "Cinema's Conquistadors," in Sight and Sound (London), November 1992.

Strick, Philip, " Blade Runner : Telling the Difference," in Sight and Sound (London), December 1992.

Torry, Robert, "Awaking to the Other: Feminism and the Ego-Ideal in Alien ," in Women's Studies (Champaign, Illinois), vol. 23, no. 4, 1994.

Elrick, Ted, "Scott Brothers' Work Showcased for UK/LA," in DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), December-January 1994–1995.

Filmography, in Premiere (Boulder), February 1996.

Dauphin, G., "Heroine Addiction," in Village Voice (New York), 26 August 1997.

Lev, Peter, "Whose Future? Star Wars, Alien, and Blade Runner ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), January 1998.

* * *

Ridley Scott has enjoyed more critical acclaim and financial success as a director of television commercials than he has as a feature filmmaker. Ironically, the very element that has made him an award-winning director of commercials—his emphasis on visual design to convey the message—has often been at the core of the criticism aimed at his films.

Though Scott began his career directing popular TV programs for the BBC, he found that his meticulous attention to detail in terms of set design and props was more suited to making commercials. Scott honed his craft and style on hundreds of ad spots for British television during the 1970s, as did future film directors Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson, Adrian Lyne, and Tony Scott (Ridley's brother). In 1979, Scott became a fixture in the American television marketplace with a captivating commercial for Chanel No. 5 titled "Share the Fantasy." Still innovative in this arena, Scott continues to spark controversy with his "pocket versions of feature films"—his term for commercials.

Scott approaches his feature films with the same emphasis on mise-en-scène that distinguishes his commercials, prompting some critics to refer to him as a visual stylist. Scott assumes control over the visual elements of his films as much as possible, rather than turn the set design completely over to the art director or the photography over to the cinematographer. Because his first feature, The Duellists , was shot in France, Scott was able to serve as his own cinematographer for that film—a luxury not allowed on many subsequent films due to union rules.

Hallmarks of Scott's style include a detailed, almost crowded set design that is as prominent in the frame as the actors, a fascination with the tonalities of light, a penchant for foggy atmospheres backlit for maximum effect, and a reliance on long lenses, which tend to flatten the perspective. While these techniques are visually stunning in themselves, they are often tied directly to plot and character in Scott's films.

Of all Scott's films, Blade Runner and Legend make the fullest use of set design to enhance the theme. In Blade Runner , the polluted, dank metropolis teems with hordes of lower-class merchants and pedestrians, who inhabit the streets at all hours. Except for huge, garish neon billboards, fog and darkness pervade the city, suggesting that urban centers in the future will have no daylight hours. This pessimistic view is in sharp contrast to the sterile, brightly lit sets found in conventional science-fiction films. Inherent in the set design is a critique of our society, which has allowed its environment to be destroyed. The overwrought set design also complements the feverish attempts by a group of androids to find the secret to longer life. Blade Runner influenced the genre with its dystopian depiction of the future, though the cluttered set design and low-key lighting were used earlier by Scott in the science-fiction thriller Alien. Legend , a fairy tale complete with elves, goblins, and unicorns, employs a simple theme of good and evil that is reinforced through images of light and darkness. The magical unicorns, for example, have coats of the purest white; an innocent, virginal character is costumed in flowing, white gowns; sunbeams pour over glades of white flowers; and light shimmers across silver streams as the unicorns gallop through the forest. In contrast, a character called Darkness (actually the Devil) looks magnificently evil in an array of blood reds and wine colors; the sinister Darkness resides in the dark, dismal bowels of the Earth, where no light is allowed to enter; and a corrupted world is symbolized by a charred forest devoid of flowers and leaves and black clouds that cover the sky. The forest set was constructed entirely inside the studio and is reminiscent of those huge indoor sets created for Fritz Lang's Siegfried. In Black Rain , Scott once again reinforced the film's theme through its mise-en-scène , though here he made extensive use of actual locations instead of relying so much on studio sets. Black Rain follows the story of two New York detectives tracking a killer through the underworld of Osaka, Japan. The two characters are frequently depicted against the backdrop of Osaka's ornate neon signs and ultramodern architecture. Shot through a telephoto lens and lit from behind, the characters seem crushed against the huge set design, which serves as a metaphor for their struggle to penetrate the culture in order to track their man.

Though Scott has forged a style that is recognizably his own, his approach to filmmaking has a precedent in German Expressionist filmmaking. The Expressionists were among the first to use the elements of mise-en-scène (set design, lighting, props, costuming) to suggest traits of character or enhance meaning. Similarly, Scott's techniques are stunning yet highly artificial, a trait often criticized by American reviewers, who too often value plot and character over visual style, and realism over symbolism.

Scott's more recent films, especially Thelma and Louise , suggest that his strongest quality all along has been an ability to create film myths that resonate in viewers' minds for years afterwards. The Duellists continues to be a haunting film despite the actors' inadequate performances, not just because of the splendidly romantic cinematography but because of the starkness of the tale itself (from Joseph Conrad); and Alien , with its own duel between a no-nonsense heroine and a hidden evil, continues to be an object of critical study, feminist and otherwise. Blade Runner , perhaps most of all of Scott's films, has seized the imagination of both movie fans and scholarly theoreticians: a 1991 volume of critical studies of the film contains a 44-page annotated bibliography, and this is before the theatrical release of the "Director's Cut," which had aficionados debating the merits of its eliminating Deckard's noiresque voiceovers and the hopeful green hills at the end, and of adding a brief shot of a unicorn. One might attribute the relative failures of Someone to Watch over Me and Black Rain , despite their visual swank, to their inability to transcend tired generic conventions, while the more recent 1492: The Conquest of Paradise seems most successful in its mythic moments—notably Columbus's first glimpse of the New World as mists sweep aside—rather than in its efforts to document the Spanish extermination of native peoples while partially exonerating Columbus himself.

Thelma and Louise , with its near-hallucinatory, flamboyantly archetypal American Western settings (bearing little relation to such specificities as "Arkansas"), debuted with much debate about how feminist it actually was in its characterizations of two "dangerous women" and in its delineations of the patriarchal causes of their doomed flight. But whatever conclusions might be drawn about the film's polemics, those unforgettable shots of Thelma and Louise whooping in delight as they light out for the territory in their T-bird convertible—red hair flying, sunglasses glinting—seem destined to enter American mythology (granted that it is too soon to rank the pair alongside Huck and Jim on the raft). Closer to tall tale than high tragedy, Thelma and Louise is memorable due not only to the script and the seemingly inevitable casting of the leads, but to Scott's realization of landscapes, from the rainy night highways (a background wash of massive dark trucks and blinding lights) to Monument Valley and other vast spaces populated by little more than swarms of police vehicles. It may well be a defining film of the early 1990s, as Blade Runner has become for the early 1980s.

—Susan Doll, updated by Joseph Milicia

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: