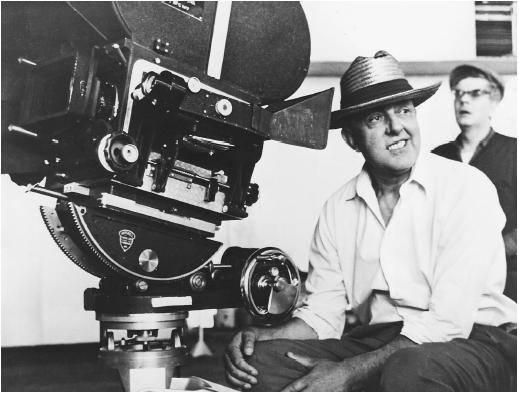

Jacques Tati - Director

Nationality:

French.

Born:

Jacques Tatischeff in Le Pecq, France, 9 October 1908.

Education:

Attended Lycée de St.-Germain-en-Laye; also attended a college of

arts and engineering, 1924.

Family:

Married Micheline Winter, 1944; children: Sophie and Pierre.

Career:

Rugby player with Racing Club de Paris, 1925–30; worked as

pantomimist/impressionist, from 1930; recorded one of his stage routines,

"Oscar, champion de tennis," on film, 1932; toured European

music halls and circuses, from 1935; served in French Army,

1939–45; directed himself in short film,

L'Ecole des facteurs

, 1946; directed and starred in first feature,

Jour de fête

, 1949; offered American television series of 15-minute programs, refused,

1950s; made

Parade

for Swedish television, 1973.

Awards:

Best Scenario, Venice Festival, for

Jour de fête

, 1949; Max Linder Prize (France) for

L'Ecole des facteurs

, 1949; Prix Louis Delluc, for

Les Vacances de M. Hulot

, 1953; Special Prize, Cannes Festival, for

Mon Oncle

, 1958; Grand Prix National des Arts et des Lettres, 1979; Commandeur des

Arts et des Lettres.

Died:

5 November 1982.

Films as Director:

- 1947

-

L'Ecole des facteurs (+ sc, role)

- 1949

-

Jour de fête (+ co-sc, role as François the postman)

- 1953

-

Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot ( Mr. Hulot's Holiday ) (+ co-sc, role as M. Hulot)

- 1958

-

Mon Oncle (+ co-sc, role as M. Hulot)

- 1967

-

Playtime (+ sc, role as M. Hulot)

- 1971

-

Trafic ( Traffic ) (+ co-sc, role as M. Hulot)

- 1973

-

Parade (+ sc, role as M. Loyal)

Other Films:

- 1932

-

Oscar, champion de tennis (sc, role)

- 1934

-

On demande une brute (Barrois) (co-sc, role)

- 1935

-

Gai Dimanche (Berry) (co-sc, role)

- 1936

-

Soigne ton gauche (Clément) (role)

- 1938

-

Retour à la terre (pr, sc, role)

- 1945

-

Sylvie et le fantOme (Autant-Lara) (role as ghost)

- 1946

-

Le Diable au corps (Autant-Lara) (role as soldier)

Publications

By TATI: articles—

"Tati Speaks," with Harold Woodside, in Take One (Montreal), no. 6, 1969.

Interview with E. Burcksen, in Cinématographe (Paris), May 1977.

Interview with M. Makeieff, in Cinématographe (Paris), January 1985.

On TATI: books—

Sadoul, Georges, The French Film , London, 1953.

Bazin, André, Qu'est ce-que le cinéma , London, 1958.

Carrière, Jean-Claude, Monsieur Hulot's Holiday , New York, 1959.

Cauliez, Armand, Jacques Tati , Paris, 1968.

Mast, Gerald, The Comic Mind , New York, 1973; revised edition, Chicago, 1979.

Kerr, Walter, The Silent Clowns , New York, 1975.

Gilliatt, Penelope, Jacques Tati , London, 1976.

Maddock, Brent, The Films of Jacques Tati , Metuchen, New Jersey, 1977.

Fischer, Lucy, Jacques Tati: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1983.

Harding, James, Jacques Tati: Frame by Frame , London, 1984.

Chion, Michel, Jacques Tati , Paris, 1987.

Dondey, Marc, Tati , Paris, 1989.

On TATI: articles—

"Mr. Hulot," in the New Yorker , 17 July 1954.

Mayer, A. C., "The Art of Jacques Tati," in Quarterly of Film, Radio, and Television (Berkeley), Fall 1955.

Simon, John, "Hulot; or The Common Man as Observer and Critic," in the Yale French Review (New Haven, Connecticut), no. 23, 1959.

Houston, Penelope, "Conscience and Comedy," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer/Autumn 1959.

Marcabru, Pierre, "Jacques Tati contre l'ironie française," in Arts (Paris), 8 March 1961.

Armes Roy, "The Comic Art of Jacques Tati," in Screen (London), February 1970.

Dale, R. C., "Playtime and Traffic, Two New Tati's," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), no. 2, 1972–73.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, "Tati's Democracy," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1973.

Thompson, K., "Parameters of the Open Film: Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), vol. 1, no. 4, 1977.

Nepoti, Roberto, "Jacques Tati," special issue, in Castoro Cinema (Firenze), no. 58, 1978.

"Tati Issue" of Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1979.

Schefer, J. L., "Monsieur Tati," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1982.

Fischer, Lucy, " Jour de fête : Americans in Paris," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), Winter 1983.

"Jacques Tati Issue" of Cinéma (Paris), January 1983.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, "The Death of Hulot," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1983.

Carriére. J. C. "Comedie à la Française," in American Film (New York), December 1985.

Thompson, Kristin, " Parade , a Review of an Unreleased Film," in Velvet Light Trap (Madison, Wisconsin), no. 22, 1986.

Fawell, J. "Sound and Silence, Image and Invisibility in Jacques Tati's Mon oncle ," in Literature and Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 18, no. 4, October 1990.

Hommel, M., and F. Hauffmann, "Hulot in de menigte. Twee kapiteins op iin schip," in Skrien (Amsterdam), no. 178, June-July 1991.

Pierre, S., "Tati est grand," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 442, April 1991.

Jullier, L., "L'art des bruits chez Jacques Tati," in Focales (Nancy Cedex), no. 2, 1993.

Olofsson, A., "Marodor i lyckoriket," in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 35, no. 4, 1993.

Teisseire, G., and others, "Jacques Tati: Playtime," in Positif (Paris), May 1993.

Charbonneau, A., "Monsieur Tati ou l'exigence du rire," in 24 Images (Montreal), no. 68-69, September-October 1993.

Douin, Jean-Luc, "Tonton Tati," in Télérama (Paris), no. 2291, 8 December 1993.

Kermabon, Jacques, "Tati architecte: La transparence, le reflet et l'ephémère,"in CinémAction (Conde-sur-Noireau), no. 75, April 1995.

Sartor, Freddy, in Film en Televisie (Brussel), no. 466, November 1996.

Salonen, Annika, "Hullunkurinen Herra Hulot," in Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 4–5, 1997.

* * *

Jacques Tati's father was disappointed that his son didn't enter the family business, the restoration and framing of old paintings. In Jacques Tati's films, however, the art of framing—of selecting borders and playing on the limits of the image—achieved new expressive heights. Instead of restoring old paintings, Tati restored the art of visual comedy, bringing out a new density and brilliance of detail, a new clarity of composition. He is one of the handful of film artists—the others would include Griffith, Eisenstein, Murnau, Bresson—who can be said to have transformed the medium at its most basic level, to have found a new way of seeing.

After a short career as a rugby player, Tati entered the French music hall circuit of the early 1930s; his act consisted of pantomime parodies of the sports stars of the era. Several of his routines were filmed as shorts in the 1930s (and he appeared as a supporting actor in two films by Claude Autant-Lara), but he did not return to direction until after the war, with the 1947 short L'Ecole des facteurs. Two years later, the short was expanded into a feature, Jour de fête. Here Tati plays a village postman who, struck by the "modern, efficient" methods he sees in a short film on the American postal system, decides to streamline his own operations. The satiric theme that runs through all of Tati's work—the coldness of modern technology—is already well developed, but more importantly, so is his visual style. Many of the gags in Jour de fête depend on the use of framelines and foreground objects to obscure the comic event—not to punch home the gag, but to hide it and purify it, to force the spectator to intuit, and sometimes invent, the joke for himself.

Tati took four years to make his next film, Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (Mr. Hulot's Holiday) , which introduced the character he was to play for the rest of his career—a gently eccentric Frenchman whose tall, reedy figure was perpetually bent forward as if by the weight of the pipe he always kept clamped in his mouth. The warmth of the characterization, plus the radiant inventiveness of the sight gags, made Mr. Hulot an international success, yet the film already suggests Tati's dissatisfaction with the traditional idea of the comic star. Hulot is not a comedian, in the sense of being the source and focus of the humor; he is, rather, an attitude, a signpost, a perspective that reveals the humor in the world around him.

Mon Oncle is a transitional film: though Hulot had abdicated his star status, he is still singled out among the characters—prominent, but strangely marginal. With Playtime , released after nine years of expensive, painstaking production, Tati's intentions become clear. Hulot was now merely one figure among many, weaving in and out of the action much like the Mackintosh Man in Joyce's Ulysses. And just as Tati the actor refuses to use his character to guide the audience through the film, so does Tati the director refuse to use close-ups, emphatic camera angles, or montage to guide the audience to the humor in the images. Playtime is composed almost entirely of long-shot tableaux that leave the viewer free to wander through the frame, picking up the gags that may be occurring in the foreground, the background, or off to one side. The film returns an innocence of vision to the spectator; no value judgements or hierarchies of interest have been made for us. We are given a clear field, left to respond freely to an environment that has not been polluted with prejudices.

Audiences used to being told what to see, however, found the freedom of Playtime oppressive. The film (released in several versions, from a 70mm stereo cut that ran over three hours to an absurdly truncated American version of 93 minutes) was a commercial failure. It plunged Tati deep into personal debt.

Tati's last theatrical film, the 1971 Traffic , would have seemed a masterpiece from anyone else, but for Tati it was clearly a protective return to a more traditional style. Tati's final project, a 60-minute television film titled Parade , has never been shown in America. Five films in 25 years is not an impressive record in a medium where stature is often measured by prolificacy, but Playtime alone is a lifetime's achievement—a film that liberates and revitalizes the act of looking at the world.

—Dave Kehr

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: