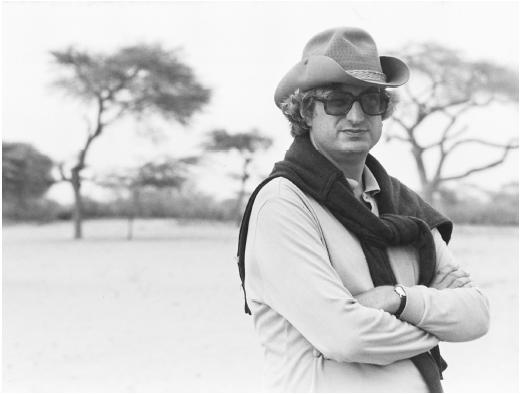

Bertrand Tavernier - Director

Nationality:

French.

Born:

Lyons, 25 April 1941.

Education:

Studied law for one year.

Family:

Married writer Colo O'Hagan (separated), two children.

Career:

Film critic for

Positif

and

Cahiers du Cinéma

, Paris, early 1960s; press agent for producer Georges de Beauregard,

1962; freelance press agent, associated with Pierre Rissient, 1965;

directed first film,

L'Horloger de St. Paul

, 1974.

Awards:

Prix Louis Delluc, for

L'Horloger de St. Paul

, 1974; Cesar Awards for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay (with

Jean Aurenche), for

Que la fête commence

, 1975; European Film Festival Special Prize, for

La Vie et rien d'autre

, 1989.

Films as Director and Co-Scriptwriter:

- 1964

-

"Une Chance explosive" episode of La Chance et l'amour

- 1965

-

"Le Baiser de Judas" episode of Les Baisers

- 1974

-

L'Horloger de Saint-Paul ( The Clockmaker )

- 1975

-

Que la fête commence ( Let Joy Reign Supreme )

- 1976

-

Le Juge et l'assassin ( The Judge and the Assassin )

- 1977

-

Des enfants gâtés ( Spoiled Children )

- 1979

-

Femmes Fatales

- 1980

-

La Mort en direct ( Death Watch )

- 1981

-

Une Semaine de vacances ( A Week's Vacation )

- 1982

-

Coup de torchon ( Clean Slate ); Philippe Soupault et le surréalisme ) (doc)

- 1983

-

Mississippi Blues ( Pays d'Octobre ) (co-d)

- 1984

-

Un Dimanche à la campagne ( A Sunday in the Country )

- 1986

-

Round Midnight ( Autour de minuit )

- 1987

-

Le Passion Béatrice

- 1988

-

Lyon, le regard intérieur (doc for TV)

- 1989

-

La Vie et rien d'autre ( Life and Nothing But )

- 1990

-

Daddy Nostalgie ( These Foolish Things )

- 1991

-

La guerre sans non ( The Undeclared War )

- 1992

-

L.627

- 1994

-

Le fille de D'Artagnan ( The Daughter of D'Artagnan ); Anywhere but Here

- 1995

-

L'appat ( Fresh Bait )

- 1996

-

Capitaine Conan ( Captain Conan )

- 1997

-

La Lettre (for TV) (d only)

- 1998

-

De l'autre côté du périph ( The Other Side of the Tracks ) (d only)

- 1999

-

Ça commence aujourd'hui ( It All Starts Today )

Other Films:

- 1967

-

Coplan ouverte le feu à Mexico (Freda) (sc)

- 1968

-

Capitaine Singrid (Leduc) (sc)

- 1977

-

Le Question (Heynemann) (pr)

- 1979

-

Rue du pied de Grue (Grandjouan) (pr); Le Mors aux dents (Heynemann) (pr)

- 1993

-

Des demoiselles ont en 25 ans ( The Young Girls Turn 25 ) (Varda) (appearance); Francois Truffaut: portraits voles ( Francois Truffaut: Stolen Portraits ) (Toubiana, Pascal) (appearance)

- 1994

-

Troubles We've Seen: A History of Journalism in War-time (pr)

- 1995

-

The World of Jacques Demy (Varda) (appearance); American Cinema (role)

- 2000

-

Il avait dans Le coeur des jardins introuvables (co-sc)

Publications

By TAVERNIER: book—

30 ans de cinéma américaine (30 Years of American Cinema) , with Jean-Pierre Coursodon, Paris.

Amis americains: entretiens avec les grands auteurs d'Hollywood , Paris, 1993.

Fragments: Portraits from the Inside , with Andre De Toth and Martin Scorsese, New York, 1996.

By TAVERNIER: articles—

"Il n'y a pas de genre à proscrire ou à conseiller . . . ," an interview with D. Rabourdin, in Cinéma (Paris), May 1975.

"Les Rapports de la justice avec la folie et l'histoire," in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), June 1976.

"Notes éparses," in Positif (Paris), December/January 1977/78.

"Blending the Personal with the Political," an interview with L. Quart and L. Rubinstein, in Cineaste (New York), Summer 1978.

"Director of the Year," International Film Guide (London, New York), 1980.

"Cleaning the Slate," an interview with I. F. McAsh, in Films (London), August 1982.

Interviews in Films in Review (New York), March and April 1983.

Interview with Michel Ciment and others, in Positif (Paris), May 1984.

Interview with Dan Yakir, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1984.

" Round Midnight ," an interview with Jean-Pierre Coursodon, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 15, no. 2, 1986.

"All the Colors: Bertrand Tavernier Talks about Round Midnight ," an interview with Michael Dempsey, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1987.

Interview with M. Ruuth, in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 29, 1987.

Interview, in Skrien (Amsterdam), Spring 1987.

Interview, in Positif (Paris), September 1989.

Interview by F. Laurendeau, in Sequences (Montreal), November 1989.

"La guerre n'est pas finie," an interview with K. Jaehne, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 18, no. 1, 1990.

Obituary, of Michael Powell, in Positif (Paris), May 1990.

"A la rencontre de Budd Boetticher," in Positif (Paris), July/August 1991.

"Journey into light," an interview with Patrick McGilligan, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1992.

Interview by F. Aude and H. Niogret, in Positif (Paris), April 1992.

"Police State," an interview with Geoff Andrew, in Time Out (London), 6 January 1993.

"Tavernier on Mackendrick," in Sight and Sound (London), August 1994.

Interview with Jean-Claude Raspiengeas, in Télérama (Paris), 3 May 1995.

Interview with Philippe Piazzo, in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), January-February 1997.

"Filming a Forgotten War: An Interview with Bertrand Tavernier," in Cineaste (New York), April 1998.

On TAVERNIER: books—

Bion, Danièle, Bertrand Tavernier: cinéaste de l'émotion , Renens, 1984.

Mereghetti, Paolo, editor, Bertrand Tavernier , Venice, 1986.

Douin, Jean-Luc, Tavernier , Paris, 1988.

Mehle, Kerstin, Blickstrategien im Kino von Bertrand Tavernier , Frankfurt, 1991.

La vida, la muerte: el cine de Bertrand Tavernier , Valencia, Spain, 1992.

Zants, Emily, Bertrand Tavernier: Fractured Narrative and Bourgeois Values , Lanham, 1999.

Hay, Stephen, Bertrand Tavernier: The Film Maker of Lyon , I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2000.

On TAVERNIER: articles—

" L'Horloger de Saint-Paul Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), May 1974.

Auty, M., "Tavernier in Scotland," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1976/77.

Hennebelle, G., and others, "Le Cinéma de Bertrand Tavernier," in Ecran (Paris), September and October 1977.

Magretta, W. R. and J., "Bertrand Tavernier: The Constraints of Convention," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1978.

"Bertrand Tavernier Dossier" in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), April 1984.

Ciment, Michel, "Sunday in the Country with Bertrand," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1984.

Harvey, Stephen, "Focus: Beatrice ," in American Film (New York), March 1988.

Riding, Alan, "Bertrand Tavernier Films Small Romances amid Wide-Scale History," in New York Times , 11 September 1990.

Seidenberg, Robert, " Daddy Nostalgia ," in American Film (New York), February 1991.

Loiseau, Jean-Claude, and others, "Capitaine Conan," in Télérama (Paris), 16 October 1996.

Vincendeau, Ginette, "Black to the Blackboard," in Sight and Sound (London), July 1999.

* * *

It is significant that Bertrand Tavernier's films have been paid little attention by the more important contemporary film critics/theorists: his work is resolutely "realist," and realism is under attack in critical quarters. Realism has frequently been a cover for the reproduction and reinforcement of dominant ideological assumptions, and to this extent that attack is salutary. Yet Tavernier's cinema demonstrates effectively that the blanket rejection of realism rests on very unstable foundations. Realism has been seen as the bourgeoisie's way of talking to itself. It does not necessarily follow that its only motive for talking to itself is the desire for reassurance; nor need we assume that the only position realist fiction constructs for the reader/viewer is one of helpless passivity (Tavernier's films clearly postulate an alert audience ready to reflect and analyze critically).

Three of Tavernier's films, Death Watch, Coup de torchon , and A Week's Vacation , while they may not unambiguously answer the attacks on realism, strongly attest to the inadequacy of their formulation. For a start, the films' range of form, tone, and address provides a useful reminder of the potential for variety that the term "classical realist text" tends to obliterate. To place beside the strictly realist A Week's Vacation the futurist fantasy of Death Watch on the one hand and the scathing, all-encompassing caricatural satire and irony of Coup de torchon on the other is to illustrate not merely a range of subject-matter but a range of strategy. Each film constructs for the viewer a quite distinct relationship to the action and to the protagonist, analyzable in terms of varying degrees of identification and detachment which may also shift within each film. Nor should the description of A Week's Vacation as "strictly realist" be taken to suggest some kind of simulated cinéma-vérité: the film's stylistic poise and lucid articulation, its continual play between looking with the protagonist and looking at her, consistently encourage an analytical distance.

Through all his films, certainly, the bourgeoisie "talks to itself," but the voice that articulates is never reassuring, and bourgeois institutions and assumptions are everywhere rendered visible and opened to question. Revolutionary positions are allowed a voice and are listened to respectfully. This was clear from Tavernier's first film, The Clockmaker , among the screen's most intelligent uses of Simenon. Under Tavernier, the original project is effectively transformed by introducing the political issues that Simenon totally represses, and by changing the crime from a meaningless, quasi-existentialist acte gratuit to a gesture of radical protest. But Tavernier's protagonists are always bourgeois: troubled, questioning, caught up in social institutions but not necessarily rendered impotent by them, capable of growth and awareness. The films, while basically committed to a well-left-of-center liberalism, are sufficiently open, intelligent, and disturbed to be readily accessible to more radical positions than they are actually willing to adopt.

Despite the difference in mode of address, the three films share common thematic concerns (most obviously, the fear of conformism and dehumanization, the impulse towards protest and revolt, the difficulties of effectively realizing such a protest in action). They also have in common a desire to engage, more or less explicitly, with interrelated social, political, and aesthetic issues. The caustic analysis of the imperialist mentality and the kind of personal rebellion it provokes (itself corrupt, brutalized, and ultimately futile) in Coup de torchon is the most obvious instance of direct political engagement. Death Watch , within its science fiction format, is fascinatingly involved with contemporary inquiries into the construction of narrative and the objectification of women. Its protagonist (Harvey Keitel) attempts to create a narrative around an unsuspecting woman (Romy Schneider) by means of the miniature television camera surgically implanted behind his eyes. The implicit feminist concern here becomes the structuring principle of A Week's Vacation. Without explicitly raising feminist issues, the film's theme is the focusing of a contemporary bourgeois female consciousness, the consciousness of an intelligent and sensitive woman whose identity is not defined by her relationship with men, who is actively engaged with social problems (she is a schoolteacher), and whose fears (of loneliness, old age, death) are consistently presented in relation to contemporary social realities rather than simplistically defined in terms of "the human condition."

In Tavernier's films through the early 1990s, he has covered a wide variety of moods, styles, and settings, with the most representative of these works linked by a common contemplative quality. His concerns are the passage of time and its effect on human relationships and the individual soul. In particular, he is interested in characters who are aged and ill, or have seen too much of the seamier aspects of human behavior. These latter works investigate how they come to terms with loved ones—especially their children.

A Sunday in the Country , set at the turn of the twentieth century, is the story of an elderly painter who resides in the country and is visited one Sunday by his reserved son and daughter-in-law, their three children, and his free-spirited daughter. The film is a pensive, poignant tale of old age and the choices people make in their lives. There is much drama and emotion in Life and Nothing But , a thoughtful war film which in fact takes place at a time when there is no fighting and bloodshed. Set after the conclusion of a war, the film concerns a soldier (Tavernier regular Philippe Noiret) who is assigned to chronicle his country's war casualties. Meanwhile, a couple of women have set out in search of their lovers, who are missing in action.

In Round Midnight , Tavernier caringly recreates the community of black jazz artists in exile in France. The film is a character study of an aged, alcoholic tenor sax legend, a composite of Bud Powell and Lester Young (and played by Dexter Gordon, himself a jazz great). He settles in Paris in 1959 and plays nightly at a famed jazz club; at the core of the story is his friendship with a young, adoring Frenchman, a dedicated jazz fan. Finally, in Daddy Nostalgia , the filmmaker examines the complex alliance between a father (Dirk Bogarde) and daughter (Jane Birkin). He is seriously ill; she visits him for an extended stay and attempts to understand their relationship, and his life.

The fact that Tavernier's recent films have (unaccountably) had very little exposure in North America must not be taken as evidence of decline. Only Daddy Nostalgie has had any wide release; the rest have gone direct to video after brief screenings in specialist theaters. All are well worth searching out, conceived and directed with Tavernier's customary intelligence and complexity. His mastery of mise-en-scène is complete, from the intimate oedipal tensions of the family scenes in Daddy Nostalgie to the spectacular and horrifying battles of Capitaine Conan , though one would not easily guess this from the wretched video of Daddy Nostalgie , a widescreen film presented in the wrong format and suggesting that Tavernier doesn't know how to frame. The other films have been treated by their distributors with more respect.

L.627 (the title refers to the Public Health Card for junkies, who get check-ups every twenty-four hours) is among the most intelligent movies in any language about the inner workings of the police, a fine example of Tavernier's refusal to make simple statements or offer the spectator clear and uncompromised moral positions, implying severe criticisms of the organization while showing sympathy and some respect for the officers who try to preserve a modicum of decency and self-respect within it. The "bait" of L'Appat is a young woman used by her two male friends to seduce wealthy men to unlatch their apartment doors so that her colleagues can burst in and rob them; while no character is admirable, none is presented without some sympathy, so that the underlying implication is, as usual with Tavernier, that it is the culture that is pervasively "wrong," not the individuals caught within it. Capitaine Conan is a fascinating study of the complexities of military service, centered on a dedicated "career officer" who has constructed for himself a personal code of honour the inherent contradictions and misguidedness of which are exposed at every step.

Tavernier remains a major figure in contemporary cinema; it is time for festivals and cinematheques to take note and honour him with retrospectives, which might serve to rectify the terrible neglect into which his work seems to have fallen.

—Robin Wood, updated by Rob Edelman and Robin Wood

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: