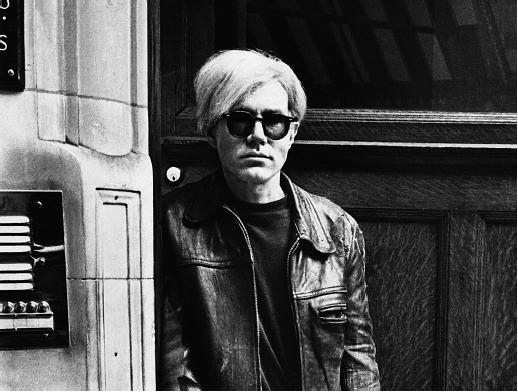

Andy Warhol - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Andrew Warhola in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, 6 August 1928. Education: Studied at Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, B.F.A., 1949. Career: Illustrator for Glamour Magazine (New York), 1949–50; commercial artist, New York, 1950–57; independent artist, New York, 1957 until his death in 1987; first silk-screen paintings, 1962; began making films, mainly with Paul Morrissey, a member of his "Factory," 1963; shot by former "Factory" regular Valerie Solanas, 1968; editor, Inter/View

Films as Director and Producer:

- 1963

-

Tarzan and Jane Regained . . . Sort Of ; Sleep ; Kiss ; Andy Warhol Films Jack Smith Filming Normal Love ; Dance Movie ( Roller Skate ); Salome and Delilah ; Haircut ; Blow Job

- 1964

-

Empire ; Batman Dracula ; The End of Dawn ; Naomi and Rufus Kiss ; Henry Geldzahler ; The Lester Persky Story ( Soap Opera ); Couch ; Shoulder ; Mario Banana ; Harlot ; Taylor Mead's Ass

- 1965

-

Thirteen Most Beautiful Women ; Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys ; Fifty Fantastics ; Fifty Personalities ; Ivy and John ; Screen Test I ; Screen Test II ; The Life of Juanita Castro ; Drunk ; Suicide ; Horse ; Vinyl ; Bitch ; Poor Little Rich Girl ; Face ; Restaurant ; Afternoon ; Prison ; Space ; Outer and Inner Space ; Camp ; Paul Swan ; Hedy ( Hedy the Shoplifter or The Fourteen-Year-Old Girl ); The Closet ; Lupe ; More Milk, Evette

- 1966

-

Kitchen ; My Hustler ; Bufferin ( Gerard Malanga Reads Poetry ); Eating Too Fast ; The Velvet Underground ; Chelsea Girls

- 1967

-

* * * * ( Four Stars ) [parts of * * * * include International Velvet ; Alan and Dickin ; Imitation of Christ ; Coutroom ; Gerard Has His Hair Removed with Nair ; Katrina Dead ; Sausalito ; Alan and Apple ; Group One ; Sunset Beach on Long Island ; High Ashbury ; Tiger Morse ]; I, a Man ; Bike Boy ; Nude Restaurant ; The Loves of Ondine

- 1968

-

Lonesome Cowboys ; Blue Movie ( Fuck ); Flesh (d Morrissey, pr Warhol)

- 1970

-

Trash (d Morrissey, pr Warhol)

- 1972

-

Women in Revolt (co-d with Morrissey); Heat (d Morrissey, pr Warhol)

- 1973

-

L'Amour (co-d, pr, co-sc with Morrissey)

- 1974

-

Andy Warhol's Frankenstein (d Morrissey, pr Warhol); Andy Warhol's Dracula (d Morrissey, pr Warhol)

- 1977

-

Andy Warhol's Bad (d Morrissey, pr Warhol)

Other Films

- 1986

-

Vamp (Wenk) (contributing artist)

Publications

By WARHOL: books—

Blue Movie , script, New York, 1970.

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) , New York, 1975.

The Andy Warhol Diaries , edited by Pat Hackett, New York, 1989.

Andy Warhol: In His Own Words , London, 1991.

Angels, angels, angels , London, 1994.

Cats, cats, cats , London, 1994.

By WARHOL: articles—

Interview with David Ehrenstein, in Film Culture (New York), Spring 1966.

"Nothing to Lose," an interview with Gretchen Berg, in Cahiers du Cinéma in English (New York), May 1967.

Numerous interviews conducted by Warhol, in Inter/View (New York).

Interview in The Film Director as Superstar , by Joseph Gelmis, Garden City, New York, 1970.

Interview with Tony Rayns, in Cinema (London), August 1970.

Interview with Ralph Pomeroy, in Afterimage (Rochester), Autumn 1970.

On WARHOL: books—

Coplans, John, Andy Warhol , New York, 1970.

Crone, Rainer, Andy Warhol , New York, 1970.

Gidal, Peter, Andy Warhol , New York, 1970.

Wilcox, John, The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol , New York, 1971.

Koch, Stephen, Stargazer: Andy Warhol's World and His Films , New York, 1973; revised edition, 1985.

Smith, Patrick S., Andy Warhol's Art and Films , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1986.

Bourdon, David, Warhol , 1989.

Finkelstein, Nat, Warhol: The Factory Years 1964–67 , London, 1989.

Gidal, Peter, Materialist Film , London, 1989.

Guiles, Fred Lawrence, Loner at the Ball: The Life of Andy Warhol , New York, 1989.

James, David E., Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties , Princeton, New Jersey, 1989.

O'Pray, Michael, Andy Warhol: Film Factory , London, 1989.

Colacello, Bob, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up , New York, 1990.

Koch, Stephen, Stargazer: The Life, World, and Films of Andy Warhol , New York, 1991.

Inboden, Gudrun, Andy Warhol: White Disaster I, 1963 , Stuttgart, 1992.

Kurtz, Bruce D., ed., Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Walt Disney , Munich and London, 1992.

Geldzahler, Henry, Andy Warhol: Portraits of the Seventies and Eighties , London, 1993.

Katz, Jonathan, Andy Warhol , New York, 1993.

Alexander, Paul, Death and Disaster: The Rise of the Warhol Empire and the Race for Andy's Millions , New York, 1994.

Cagle, Van M., Reconstructing Pop/Subculture: Art, Rock, and Andy Warhol , Thousand Oaks, California, 1995.

Tillman, Lynne; photographs by Stephen Shore, The Velvet Years: Warhol's Factory, 1965–67 , New York, 1995.

Suárez, Juan Antonio, Bike Boys, Drag Queens, and Superstars: Avant-Garde, Mass Culture, and Gay Identities in the 1960s Underground Cinema , Bloomington, Indiana, 1996.

Bockris, Victor, Warhol , New York, 1997.

Pratt, Alan R., editor, The Critical Response to Andy Warhol , Westport, Connecticut, 1997.

MacCabe, Colin, with Mark Francis and Peter Wollen, editors, Who Is Andy Warhol? London, 1997.

Dalton, David, Andy Warhol: The Factory Years, 1964–1967 , New York, 2000.

On WARHOL: articles—

Stoller, James, "Beyond Cinema: Notes on Some Films by Andy Warhol," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1966.

Tyler, Parker, "Dragtime and Drugtime: or Film à la Warhol," in Evergreen Review (New York), April 1967.

"Warhol," in Film Culture (New York), Summer 1967.

Lugg, Andrew, "On Andy Warhol," in Cineaste (New York), Winter 1967/68 and Spring 1968.

Rayns, Tony, "Andy Warhol's Films Inc.: Communication in Action," in Cinema (London), August 1970.

Heflin, Lee, "Notes on Seeing the Films of Andy Warhol," in Afterimage (Rochester), Autumn 1970.

Bourdon, David, "Warhol as Filmmaker," in Art in America (New York), May-June 1971.

Cipnic, D.J., "Andy Warhol: Iconographer," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1972.

Larson, R., "A Retrospective Look at the Films of D. W. Griffith and Andy Warhol," in Film Journal (New York), Fall-Winter 1972.

James, David E., "The Producer as Author," in Wide Angle (Baltimore, Maryland), vol. 7, no. 3, 1985.

Cohn, L., obituary in Variety (New York), 25 February 1987.

Babitz, E., "The Soup Can as Big as the Ritz," in Movieline , November 1989.

Currie, C., "Andy Warhol: Enigma, Icon, Master," in Semiotica , vol. 80, no. 3–4, 1990.

Huhtamo, E., "Valkokankaan suuri ei-kukaan. Andy Warhol elokuvantekijana," Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 5, 1990.

Diana, M., "Blow Cinema," in Segnocinema (Vicenza), vol. 10, no. 46, November 1990.

Ulver, S., "Andy Warhol. Realita a mytus," Film and Doba , vol. 37, no. 1 Spring 1991.

Finnane, Gabrielle, Kosmorama (Copenhagen), vol. 37, no. 198, Winter 1991.

Tully, Judd, "15 Minutes Later: Warhol Now," in ARTnews , March 1992.

Byron, Christopher, "Andy's Magic Money Machine," in New York , 30 November 1992.

Dixon, W. W., "The Early Films of Andy Warhol," in Classic Images (Muscatine, Iowa), no. 214, April 1993.

Stevens, Mark, "Saint Andy," in New York , 23 May 1994.

Assayas, O., "Andy Warhol," in Positif (Paris), no. 400, June 1994.

Taubin, A., "My Time Is Not Your Time," in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 4, no. 6, June 1994.

Long, Marion, "The Andy Warhol Museum," in Omni , June 1994.

Adams, Brooks, "Industrial-strength Warhol," in Art in America , September 1994.

James, D. E., "The Warhol Screenplays: Interview with Ronald Tavel," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), no. 11, 1995.

Alexander, Paul, "Murky Image," in ARTnews , February 1995.

Bandy, Mary Lea, "Another Cinema Must Be Saved," in Journal of Film Preservation (Brussels), no. 50, March 1995.

Peck, Ron, and Stephen Thrower, "Directed by Paul Morrissey. An Interview with Paul Morrissey," in Eyeball , no. 4, Winter 1996.

On WARHOL: film—

American Masters: Superstar—The Life of Andy Warhol , 1990.

* * *

By the time he screened his first films in 1963, Andy Warhol was well on his way to becoming the most famous "pop" artist in the world, and his variations on the theme of Campbell's soup cans had already assumed archetypal significance for art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Given Warhol's penchant for the automatic and mass-produced, his movement from sculpture, canvas, and silk-screen into cinema seemed logical; and his films were as passive, as intentionally "empty", as significant of the artist's absence as his previous work or as the image he projected of himself. One of his earliest films, Kiss , was no more nor less than a series of people kissing in closeup, each scene running the three-minute length of a 16mm daylight reel, complete with flash frames at both ends. But it was his 1963 film Sleep , a six-hour movie comprised of variously framed shots of a naked sleeping man, which made Warhol a star on the burgeoning New York underground film scene. As though to dispel any doubts that his message was the medium, Warhol followed Sleep with Empire , an eight-hour stationary view of the Empire State Building, creating a kind of cinematic limit case for the Bazinian integrity of the shot. It was a film of such conceptual significance that if it did not exist it would have to be invented; yet it was a film that was equally unwatchable (even Warhol refused to sit through it).

During the period 1963 to 1967, Warhol made some fifty-five films, ranging in length from four minutes ( Mario Banana , 1964) to twenty-five hours ( * * * * , 1967). All were informed by the passive, mechanical aesthetic of simply turning on the camera to record what was in front of it. Generally, what was recorded were the antics of Warhol's E. 47th Street "Factory" coterie—a host of friends, artists, junkies, transvestites, rock singers, hustlers, fugitives, and hangerson. Ad-libbing, "camping," being themselves (and often more than themselves) before the unblinking eye of Warhol's camera, they became "superstars"—underground celebrities epitomizing Warhol's consumer-democratic ideal of fifteen minutes' fame for everyone.

Despite Warhol's cultivated image as the "tycoon of passivity," his films display a cool but very dry wit. Blow Job , for example, consisted of thirty minutes of a closeup of the expressionless face of a man being fellated outside the frame—a coyly humorous presentation of a forbidden act in an image perversely composed as a denial of pleasure (for the actor and the audience). Mario Banana simply presented the spectacle of transvestite Mario Montez eating bananas while in drag. Harlot , Warhol's first sound film, featured Mario (again eating bananas) sitting next to a woman in an evening dress, with the entirety of the virtually inaudible dialogue coming from three men positioned off-screen.

In the course of his films, Warhol seemed to be retracing the history of the cinema, from silence to sound to color ( Chelsea Girls ); from a fascination with the camera's "documentary" capabilities ( Empire ) to attempts at narrative by 1965. Vinyl , an adaption of Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange , involved a single high-angle camera position tightly framing a group of mostly uninvolved factory types, with protagonist Gerard Malanga sitting in a chair, reading his lines off a script on the floor, and being tortured with dripping candle wax and a "popper" overdose. When the camera accidently fell over in the middle of the proceedings, it was quickly returned to its original position without a break in the action. My Hustler offered a modicum of story, audible dialogue, and two shots—one of them a repetitive pan from a gay man talking to friends on the deck of a Fire Island beach house to his hired male prostitute sunning himself on the beach. The second shot, which fails to reveal the outcome of a wager made in the first section, shows the hustler and another man taking showers and grooming themselves in a crowded bathroom (a scene which made the pages of Life magazine for its brief male nudity).

It was Chelsea Girls , however, which resulted in Warhol's breakthrough to national and international exposure. A three-hour film in black-and-white and color, shown on two screens at once, it featured almost all the resident "superstars" in scenes supposedly taking place in various rooms of New York's Chelsea Hotel. After Chelsea Girls' financial success, subsequent Warhol films like I, a Man ; Bike Boy ; Nude Restaurant ; and Lonesome Cowboys became a bit more technically astute and conventionally feature-length. Simultaneously, the scenes taking place in front of the camera in these films, while they maintained their bizarre, directionless, and ad-libbed quality, became more sensational in their presentation of nudity and sex. Warhol's last hurrah, Lonesome Cowboys , was actually shot in Arizona. It featured a number of "superstars" dressing in western garb, posing and walking through a nearly non-existent story amongst western movie sets. It was the last film Warhol completed before he was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt by marginal factory character Valerie Solanas.

Warhol's shooting marked the beginning of a period of reclusiveness for the artist. Subsequent "Warhol" films were the product of cohort and collaborator Paul Morrissey, who has been credited with the increasing commercialism of the 1967 films (not to mention the decline of the factory "scene"). While Warhol lay in the hospital recovering from gunshot wounds, Morrissey completed a film on his own titled Flesh —a series of episodes basically recounting a day in the life of Joe Dallesandro (who appears nude more often than not), featuring Warhol-like performances and camera work, but adding a discernible story line and even character motivations.

From 1970 to 1974, Morrissey's films under Warhol's name quickly became not only more commercial, but more technically accomplished and traditionally plotted as well. After Trash , a kind of watershed film that featured Joe and Holly Woodlawn in a narrative comedy about some marginal New York junkies and low-lifes, Morrissey even began to tone down the nudity. Women in Revolt , which was virtually a full-fledged melodrama, featured three transvestites playing the women of the title. Heat , shot in Los Angeles, had Dallesandro and New York cult actress/screen personality Sylvia Miles playing out a sleazy remake of Sunset Boulevard. L'Amour took the whole Morrissey coterie to Paris.

Morrissey's big step into mainstream filmmaking came with the 1974 production of Andy Warhol's Frankenstein , a preposterously gory, tongue-in-cheek horror film rendered in perfectly seamless, classical Hollywood style, and in a highly accomplished 3-D process. As outrageous as it was in its surrealistically bloody excess, and for all its "high-camp" attitude, the film bore almost no resemblance to the films of Andy Warhol; nor did Morrissey's Blood for Dracula , made at the same time, with virtually the same cast, but without 3-D. Since that time, Morrissey has pursued a career apart from Warhol's name as an independent commercial filmmaker.

—Ed Lowry

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: