Malcolm X - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1992

Director: Spike Lee

Production: Marvin Worth and Spike Lee for 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, in association with Largo International N.V.; 35mm; running time: 201 minutes; released 1 November 1992 by Warner Brothers. Filmed in Saudi Arabia and the USA.

Producer: Marvin Worth, Spike Lee; screenplay: Arnold Perl, Spike Lee, based on The Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley; photography: Ernest Dickerson; editor: Barry Alexander Brown; assistant directors: Randy Fletcher, H. H. Cooper, Dale Pierce, Samir Seif, Ntshavheni Wa Luruli; production design: Wynn Thomas; art director: Tom Warren; music: Terence Blanchard; sound editor: Skip Lievsay; sound recording: Rolf Pardula; costumes: Ruth E. Parker; choreography: Otis Sallid; stunt coordination: Jeff Ward.

Cast:

Denzel Washington (

Malcolm X

); Angela Bassett (

Betty Shabazz

); Albert Hall (

Baines

); Al Freeman Jr. (

Elijah Muhammad

); Spike Lee (

Shorty

); Delroy Lindo (

West Indian Archie

); Theresa Randle (

Laura

); Kate Vernon (

Sophia

); Lonette McKee (

Louise Little

); Tommy Hollis (

Earl Little

); James McDaniel (

Brother Earl

); Nelson Mandella (Himself); Ossie Davis (Himself).

Publications

Script:

Lee, Spike, with Ralph Wiley, By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X, including the Screenplay , New York, 1992.

Hardy, James E., Spike Lee: Filmmaker , Broomall, 1995.

Jones, K. Maurice, Spike Lee & the African American Filmmakers: A Choice of Colors , Brookfield, 1996.

Haskins, Jim, Spike Lee: By Any Means Necessary , New York, 1997.

Chapman, Ferguson, Spike Lee , Mankato, 1998.

McDaniel, Melissa, Spike Lee: On His Own Terms , Danbury, 1999.

Articles:

Hollywood Reporter , 10 November 1992.

Variety , 10 November 1992.

Newsweek , 16 November 1992.

McCarthy, T., Variety (New York), 16 November 1992.

Chicago Tribune , 18 November 1992.

Christian Science Monitor , 18 November 1992.

Los Angeles Times , 18 November 1992.

New York Times , 18 November 1992.

Washington Post , 18 November 1992.

Entertainment Weekly , 20 November 1992.

Time (New York), 23 November 1992.

Harrell, Alfred D., " Malcolm X : One Man's Legacy to the Letter," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 73, no. 11, November 1992.

Crowdus, Gary, and Dan Georgakas, "Interview with Spike Lee," in Cineaste (New York), Winter 1992/1993.

Amiel, V., and others, Positif (Paris), February 1993.

Baecque, A. de., "Docteur Spike et Mr. Lee," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), February 1993.

Roy, A, "La nouvelle histoire," in 24 Images (Montreal), February 1993.

Alexander, K., Sight and Sound (London), March 1993.

Welsh, J. M., Films in Review (New York), March 1993.

Riley, V., Cinema Papers (Melbourne), May 1993.

"Malcolm Little's Big Sister," in New Yorker , vol. 70, no. 47, 30 January 1995.

Reid, M.A., "The Brand X of Post Negritude Frontier," in Film Criticism (Meadville), vol. 20, no. 1/2, 1995/1996.

Bowman, James, "Spike Lee: 'Artist'," in National Review , vol. 50, no. 14, 26 July 1999.

* * *

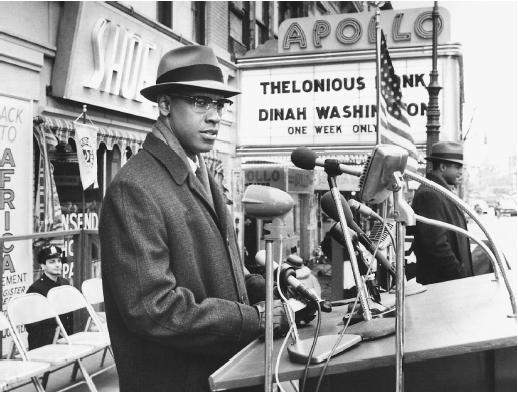

Malcolm X is the first film about an African American to be given a blockbuster budget by a Hollywood studio. That the film was made at all, much less as an epic, is primarily due to writer/director Spike Lee's history of producing controversial films that make money. Not surprisingly, Malcolm X was surrounded by racially-based tensions from the onset. Lee used racial considerations to wrest control of the project from white directors only to find himself maligned by some African American intellectuals who felt he was not qualified to take on so weighty a subject. Yet another racial nuance arose when Warner Brothers refused to approve completion funding after Lee went over budget. The director had to obtain millions in gifts from prominent African American entertainers and athletes to continue the film while Warner Brothers feuded with a bond company.

Despite this considerable pre-release sound and fury, including numerous predictions in the press that the film would surely inflame white and/or black audiences to violence, when Malcolm X finally appeared, public reaction was remarkably subdued. Rather than provoking his audiences with a film about social and racial conflict, Lee had opted for a hagiographic script stressing the theme of personal redemption. The three main sections of the film might easily have been subtitled "Malcolm the Criminal," "Malcolm the Prophet," and "Malcolm the Martyr."

After sensationalistic opening credits in which an X becomes a burning American flag and contemporary conflicts between African Americans and police are referenced, the film opens with Malcolm in his zoot suit period. An elaborate dance hall sequence has Malcolm hurrying home a respectable black woman in order to return for a tryst with Sophia, a white woman who will become his consort. He soon becomes part of Harlem's crime scene and is shown at bars handling gambling transactions but not pimping or selling drugs, other facets of his criminal years. After a fallout with West Indian Archie, the mob boss, Malcolm and his sidekick Shorty flee to Boston where they become house robbers until caught and sent to prison. The housebreaking is mainly played for laughs as are Malcolm's repeated hair straightening shampoos, painful procedures used in his autobiography to symbolize self-hatred and wanting to be white.

The prison sequences dramatize Malcolm's conversion to the Nation of Islam by a fellow inmate who will later grow jealous of his pupil's fame. This is one of many departures from the autobiography Lee vehemently insists was his final guide in shaping the script. In reality Malcolm's conversion was mainly the work of his immediate family and daily correspondence from Elijah Muhammad, the sect's leader.

Following his release from prison, Malcolm is shown having a meteoric rise through the ranks of the Nation until he is second in importance only to Elijah Muhammad. Viewers unfamiliar with the movement are likely to get the impression that it was much larger than it was (a few thousand at most), but Malcolm's pivotal role in its growth and public image is on target. His anti-white speeches and virulent attacks on civil rights leaders are mainly kept off screen while his equally strong views on personal and community self-help are spotlighted. His personal life, particularly his marriage, is projected as exemplary. In that regard, Denzel Washington who does a superb job conveying the zeal, body language, and speaking style of the public Malcolm renders a private Malcolm who is rather saccharine and humorless.

The least convincing aspects of the film chronicle Malcolm's pilgrimage to Mecca where he discovers the Nation is regarded as heretical because of its teachings that all white people are devils. Upon his return to America, Malcolm breaks with the Nation to form rival religious and secular organizations. From what is projected on the screen Malcolm's motivation appears to be disillusionment with Elijah Muhammad's spiritual authority compounded by knowledge of Elijah's sexual infidelities. What robs these crucial moments in Malcolm's life of their dynamism is the complete omission of Malcolm's subsequent trips to Africa and the Middle East.

During those journeys Malcolm met many heads of state, the majority of whom considered themselves socialists and revolutionaries. They urged him to join the civil rights movement for an integrated America and to internationalize the African American struggle by making it an issue at the United Nations. Malcolm X followed that advice by taking steps to mend the feud he had instigated with Martin Luther King and to align his new secular organization, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, with the mainstream civil rights movement. Omission of this trajectory distorts the account of his final year.

Lee takes great pains to show us CIA agents photographing Malcolm in Egypt and FBI agents bugging his phone and premises in New York. Given the context Lee has set up, this seems simple racist paranoia rather than a concern about Malcolm's international contacts and his ideological drift to the political left. Rather than probe this aspect of Malcolm's final days, the film takes the easier course of presenting the mechanics of the assassination in great detail. What amounts to an epiphany has been signalled from the start by various devices, including Malcolm's repeated visual recall of his father's persecution by klansmen. His own assassins are shown as Muslims solely motivated by religious fanaticism.

Ossie Davis's funeral oration is used to segue to a montage sequence in which Malcolm's name and image become the symbols of integrity and rebellion for black America. Black children chant, "I am Malcolm," and Nelson Mandella appears as a school teacher imploring us all to study Malcolm's life. The film concludes with engaging documentary footage of the real Malcolm. These few moments offer images of a man far more vital and complex than the staid icon depicted in the fictional portions of the film.

Both the strengths and weaknesses of Malcolm X stem from the decision to make it an inspirational biopic. The hero's worst behavior, his most controversial ideas, and his changing political views have all been muted. What is projected is the story of how a young black man caught in the racism and crime of the big city completely remade his life and finally even shed off racism only to be gunned down by former compatriots whose vision could not grow as full as his own.

Lee's response to criticism that his film is too superficial is that he did not intend it to be the last word on Malcolm X but a stimulus for further study, particularly by young people. Using that standard as a measure, Lee more than met his goal. The baseball caps with X on them that he used to promote the film became omnipresent in black communities. The film also sent sales of books by and about Malcolm into the millions of copies. Despite a running time of 201 minutes, the film turned a modest profit while garnering its share of awards at various national and international film events.

—Dan Georgakas