One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1975

Director: Milos Forman

Production: Fantasy Films; Deluxe color, 35mm; running time: 134 minutes.

Producers: Saul Zaentz, Michael Douglas; screenplay: Lawrence Hauben, Bo Goldman, based on the novel by Ken Kesey; photography: Haskell Wexler; editor: Richard Chew, Lynzee Klingman, Sheldon Kahn; assistant directors: Irby Smith, William St. John; production design: Paul Sylbert; art director: Edwin O'Donovan; music: Jack Nitzsche; sound editor: Mary McGlone, Robert R. Rutledge, Veronica Selver; sound recording: Lawrence Jost; costumes: Agnes Rodgers.

Cast: Jack Nicholson ( Randall P. McMurphy ); Louise Fletcher ( Nurse Ratched ); Will Sampson ( Chief Bromden ); Brad Dourif ( Billy Bibbit ); William Redfield ( Harding ); Christopher Lloyd ( Taber ); Sydney Lassick ( Cheswick ); Danny De Vito ( Martini ); Delos V. Smith Jr. ( Scanlon ); Scatman Crothers ( Spivey ); Marya Small ( Candy ); William Duell ( Sefelt ); Louisa Moritz ( Rose ); Dean R. Brooks ( Dr. Spivey ); Michael Berryman ( Ellis ).

Awards: Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Nicholson), Best Actress (Fletcher), and Best Adapted Screenplay, 1975.

Publications

Books:

Poizot, Claude, Milos Forman , Paris, 1987.

Slater, Thomas J., Milos Forman: A Bio-Bibliography , Connecticut, 1987.

Aycock, Wendell, and Michael Schoenecke, Film and Literature: A Comparative Approach to Adaptation , Lubbock, Texas, 1988.

Brode, Douglas, The Films of Jack Nicholson , New York 1990, 1996.

Goulding, Daniel J., Five Filmmakers , Indianapolis, 1994.

Forman, Milos, and Jan Novak, Turnaround: A Memoir , London, 1994, 1996.

Articles:

Walker, B., Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1975.

Variety (New York), 19 November 1975.

Cowie, P., and A. Ayles, Focus on Film (New York), Winter 1975–76.

MacReadie, M., Films in Review (New York), January 1976.

Milne, T., Monthly Film Bulletin (London), February 1976.

Treilhou, M.C., "Une vielle imagerie de la follie" in Cinéma (Paris), January 1976.

Maupin, F., Image et Son (Paris), February 1976.

Combs, R., Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1976.

Benoit, C., Jeune Cinéma (Paris), March 1976.

Ciment, M., "Une expérience américaine" in Positif (Paris), March 1976.

Martin, M., Ecran (Paris), March 1976.

Dawson, I., Cinema Papers (Melbourne), March-April 1976.

Sineux, M., "Big Mother Is Watching you" in Positif (Paris), March 1976.

Gow, G., Films and Filming (London), April 1976.

Daney, S., "Réserves" in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1976.

Van Wert, W., "An Aerial View of the Nest" in Jump Cut (Berkeley), Summer 1976.

Hunter, I., Cinema Papers (Melbourne), June-July 1976.

McCreadie, Marsha, " One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest : Some Reasons for One Happy Adaptation," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 5, no. 2, Spring 1977.

Safer, E.B., "'It's the Truth Even if It Didn't Happen': Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 5, no. 2, Spring 1977.

Wexler, Haskell, and M. Douglas, in American Film , vol. 4, no. 10, September 1979.

Gow, G., in Films and Filming (London), no. 422, December 1989.

Warchol, T., "The Rebel Figure in Milos Forman's American Films," in New Orleans Review , vol. 17, no. 1, 1990.

Sodowsky, G.R., and R.E. Sodowsky, "Different Approaches to Psychopathology and Symbolism in the Novel and Film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ," in Literature and Psychology , vol. 37, no. 1/2, 1991.

Zubizarreta, J., "The Disparity of Point of View in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 22, no. 1, January 1994.

Raskin, R., "Set Up/Pay-Off and a Related Figure," in P.O.V. , no. 2, December 1996.

* * *

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest —the first film to win Academy Awards for Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Screenplay since It Happened One Night in 1934—is more than a superlative human drama. It is, on a broader level, one of the seminal works of its time in that it keenly reflects the systematic stifling of individuality within post-World War II American society.

The year is 1963, and Randall Patrick McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) is a new patient in a mental ward. He has been sent there from a prison work farm because he is a nonconformist, and so the authorities, having labelled him "belligerent," "resentful" and "lazy," want to evaluate him and determine if he is mentally ill.

McMurphy's "problem" is that he is a logic-minded individual in a society ruled by bureaucratic illogic. McMurphy dares to think for himself, and question authority. He resists taking his medication, and makes a perfectly rational declaration to Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher), the ward's head nurse: "I don't like the idea of taking something if I don't know what it is." Her immediate response— "Don't get upset, Mr. McMurphy"—mirrors the manner in which those in power will pigeonhole the individual who questions the rules. Of course, McMurphy does not belong in a mental ward, but his objection to blind authority makes him as much a threat to society as the worst kind of sociopath. "He's not crazy," one of the hospital doctors tellingly observes at one point, "but he's dangerous."

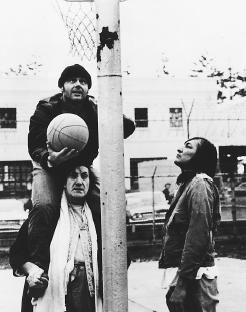

The situation on Nurse Ratched's ward goes directly against McMurphy's nature. His fellow patients are compliant and spiritless. They lack individuality, and are so drugged out on medication that their emotions are warped and exaggerated. The two key ones are Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), who incessantly stutters, and Chief Bromden (Will Sampson), a towering Indian who is presented as being deaf and dumb. McMurphy eventually learns that many of the men are self-committed, and have the freedom to leave at any time they choose. In other words, they have been so repressed by society that they have willingly accepted their fate.

McMurphy maintains his individuality by wearing jeans and colored shirts, while his fellow patients mostly are garbed in white, antiseptic hospital gowns. He promptly goes about goading the men, and showing them that it is better to try and fail than to meekly accept an unsatisfactory status quo. From the outset, he attempts to elicit a response from Chief Bromden, who eventually reveals to McMurphy that he indeed can speak and hear, but has chosen to close himself off from a society that is neck-deep in hypocrisy.

McMurphy and his irrepressible spirit are the best therapy for the men, who soon begin using their minds and expressing their feelings. The major villain of the piece is Nurse Ratched. Beneath her outwardly soothing demeanor is a neurotic, sexually repressed woman who relishes controlling the patients. She wants McMurphy kept in the hospital rather than returned to the work farm, because she is determined to break him. She knows that he will be set free once his prison sentence is completed. If he remains in the hospital, he will be under her control.

The mental ward in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest serves as a metaphor for American society, the point being that citizens are inmates of that society. They are expected to conform, by fitting in as members of a status quo. Even more specifically, as a mirror of post-World War II America, the scenario depicts a specific point in history where conformity was encouraged and free-thinking was a perilous endeavor. During the late 1940s and 50s, the House Un-American Activities Committee was allowed to strip citizens of their constitutional rights, throw them in jail, blacklist them from their jobs. In the 1960s came the escalation of the war in Vietnam; "good, patriotic Americans" supported the war, while "un-American communist dupes" protested it. One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest takes on a political edge when McMurphy urges the patients to "be good Americans" and vote for changing their work detail schedule so that they may watch a World Series game on television. The analogy here is that it is the American way to think and choose for oneself, and even change a system if that system does not benefit the majority. Furthermore, what is more American than watching baseball! By coming together as a group and altering the rules, the men simply are exercising their rights as American citizens.

It is most interesting, then, that the film's director, Milos Forman, is not American-born. He is from Czechoslovakia, and was one of the leading directors of his country's "new wave" before Russian tanks rolled through the streets of Prague in August, 1968. As such, his background allows him insight into the manner in which freedom of expression may be stifled by authority.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest also reflects on the sexual repression of pre-1960s American society. McMurphy had been jailed for statutory rape, yet he points out that his sex partner was "fifteen going on thirty-five. . . she told me she was eighteen, and was very willing. . . ." His argument is that he had not committed rape, or sexually abused a child—his partner was acquiescent, and presented herself as above the age of consent, so where is his crime? Additionally, in group therapy sessions, Nurse Ratched constantly brings up topics relating to problems the men have had with wives and girlfriends. Near the finale, McMurphy smuggles two young women into the ward, and Billy Bibbit loses his virginity to one of them. Afterwards, he no longer stutters. "No, I'm not," he proudly responds to Nurse Ratched's asking him if he is "ashamed." But the nurse craftily exploits Billy's weaknesses. She summarily squeezes the manhood out of him by declaring, "What worries me is how your mother's going to take this." Not only does Billy begin stammering again, he promptly commits suicide.

McMurphy, the autonomous rapscallion, might have escaped to freedom during all of this. But he has been transformed by his stay in the ward in that he has developed a sense of responsibility towards his new-found friends, and feels compelled to remain on the scene. He knows that Nurse Ratched—the twisted authority figure in a repressed society—is directly responsible for Billy's suicide. While McMurphy's fate is a sad one—he is lobotomized into a glassy-eyed zombie—the story ends on a positive note as Chief Bromden crashes out of the ward to freedom. The point—ever so meaningfully illustrated—is that the individual may fail in his quest for liberation, but he still may inspire those around him. His failure is no reason for the next person to remain compliant.

—Rob Edelman

please e-mail me back with any suggestions about more good books like this i could read