David Mamet - Writer

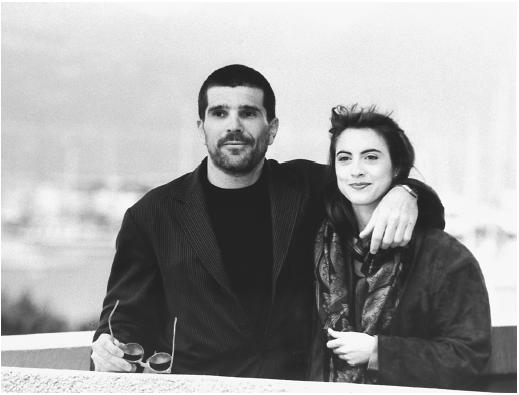

Writer and director and actor. Nationality: American. Born: Chicago, Illinois, 30 November 1947. Education: Studied acting at the Neighborhood Playhouse, 1968–69; Goddard College, B.A. (English), 1969. Family: Married 1) Lindsay Crouse (an actress), 21 December 1977 (divorced); children: Willa, Zosia; 2) married Rebecca Pidgeon (an actress, singer, and songwriter), 22 September 1991; children: Clara. Career: Worked as a busboy, Second City Theatre, Chicago, a stagehand, Hull House Theatre, Chicago, and as factory worker, real estate agent, window washer, office cleaner, taxi driver, truck driver, short order cook, and salesperson; actor in New England summer theatre productions, 1969; special lecturer in drama, Marlboro College, Marlboro, Vermont, 1970; artist-in-residence and instructor in drama, Goddard College, Plainfield, Vermont, 1971–73; founding member and artistic director, St. Nicholas Company, Plainfield, Vermont, 1972; founder (with others), 1973, artistic director, 1973–76, member of the board of directors, beginning in 1973, St. Nicholas Theatre Company, Chicago; faculty member, Illinois Arts Council, Chicago, 1974; contributing editor, Oui , 1975–76; visiting lecturer, University of Chicago, Chicago, 1975–76 and 1979; teaching fellow at the School of Drama, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 1976–77; associate artistic director, 1978–79, playwright-in-residence, 1978–84, Goodman Theatre, Chicago; visiting lecturer at the Tisch School of the Arts, 1981, founder of the Atlantic Theatre Company, 1988, and chair of the Atlantic Theatre Company board of

Films as Writer:

- 1979

-

A Life in the Theater (Browning, Gutierrez—for TV)

- 1981

-

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Rafelson)

- 1982

-

The Verdict (1982)

- 1986

-

About Last Night. . . (Zwick) (from his play Sexual Perversity in Chicago )

- 1987

-

The Untouchables (De Palma); House of Games (+ d)

- 1988

-

Things Change (+ d)

- 1989

-

We're No Angels (Jordan)

- 1991

-

Uncle Vanya (Mosher—for TV) (translation); Homicide (+ d)

- 1992

-

Glengarry Glen Ross (Foley); Hoffa (DeVito) (+ assoc pr); The Water Engine (Schachter—for TV) (+ ro)

- 1993

-

Rising Sun (Kaufman) (uncredited); A Life in the Theater (Mosher—for TV) (+ exec pr)

- 1994

-

Texan (Williams—for TV); Oleanna (+ d); Vanya on 42nd Street (Malle)

- 1996

-

American Buffalo (Corrente)

- 1997

-

The Spanish Prisoner (+ d); Wag the Dog (Levinson); The Edge (Tamahori)

- 1998

-

Ronin (Frankenheimer) (as Richard Weisz)

- 1999

-

Lansky (McNaughton) (for TV) (+ exec pr); The Winslow Boy (+ d)

- 2000

-

Lakeboat (Mantegna); Whistle (Lumet); State and Main (+ d)

Films as Actor:

- 1984

-

Sanford Meisner: The American Theatre's Best Kept Secret (Doob) (as Himself)

- 1986

-

Black Widow (Rafelson) (as Herb)

Publications

By MAMET: books (nonfiction)—

On Directing Film , New York, 1991.

Cabin: Reminiscence and Diversions , New York, 1992.

A Whore's Profession: Notes and Essays , London and Boston, 1994.

Jafsie and John Henry: Essays , New York, 1999.

On Acting , New York, 1999.

By MAMET: articles—

"I Lost It at the Movies," interview with P. Biskind, in American Film (Farmingdale, New York), vol. 12, no. 8, June 1987.

Interview in Time Out (London), 12 August 1998.

Interview in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 8, no. 10, October 1998.

Interview in Interview (New York), April 1998.

"The Spanish Prisoner" and "Writing and Directing The Spanish Prisoner," in Scenario (Rockville, Maryland), vol. 4, no. 1, 1998.

On MAMET: books—

Bigsby, C. W. E., David Mamet , London, 1985.

Carroll, Dennis, David Mamet , New York, 1987.

Dean, Anne, David Mamet: Language as Dramatic Action , Rutherford, New Jersey, and London, 1990.

Trussler, Simon, Malcolm Page, and Steven Dykes, File on Mamet , New York, 1991.

Brewer, Gay, David Mamet and Film: Illusion/Disillusion in a Wounded Land , Jefferson, North Carolina, 1993.

McDonough, Carla J., Staging Masculinity: Male Identity in Contemporary American Drama , Jefferson, North Carolina, 1997.

Kane, Leslie, Weasels and Wisemen: Ethics and Ethnicity in the Work of David Mamet , New York, 1999.

On MAMET: articles—

"David Mamet," in Film Dope (Nottingham), no. 38, December 1987.

Weinberger, M., and others, "Engrenages," in Cinéma 87/88 (Paris), no. 427, 3 February 1988.

Hoberman, J., "Identity Parade," in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 1, no. 7, November 1991.

Brewer, G., "Studied Simplicity," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 20, no. 2, April 1992.

Fisher, Bob, "Minting a Screen Version of American Buffalo ," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 77, no. 2, February 1996.

Hudgins, Christopher, "Lolita 1995: The Four Filmscripts," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 25, no. 1, January 1997.

Rosenbaum, J., "Mamet and Hitchcock: The Men Who Knew Too Much," in Scenario (Rockville, Maryland), vol. 4, no. 1, 1998.

* * *

From stage playwright to screenwriter is a common enough jump, but relatively few playwrights have gone on to become directors. And none, with the exception of Marcel Pagnol, has done so as successfully as David Mamet. Like Pagnol, Mamet has been able to use his theatrical prestige to resist crass commercial pressures. His films as writer-director are unmistakably personal, made without interference or compromise. The same hasn't always been true of his scripts for other directors, as he readily acknowledges in On Directing Films : "Working as a screenwriter-for-hire, one is in the employ not of the eventual consumers (the audience, whose interests the honest writer must have at heart), but of speculators, whose ambition . . . is not to please the eventual consumer, but to extort from him as much money as possible."

Nonetheless, clear thematic preoccupations run through all his film work, whether as writer or as director. The characters that fascinate him are those on the precarious margins of society: conmen, salesmen and hucksters, cops and petty criminals. He is concerned with the codes these fringe people live by, and those they break. Matters of trust and betrayal, illusion and deception, confidence bestowed and confidence betrayed, loom large in his work. Along with these codes goes the jargon: in his films as in his plays, Mamet is famous for the speed and ferocity of his dialogue, the obsessive, almost ritualistic repetitions of words and phrases. Underlying all this is a despairing sense of the corruption of the American Dream, the busted illusion of the pursuit of happiness that haunts a sour, wounded society. In his own typically eloquent words, "My characters are trapped in the destructive folds of the public myths on my country." His first script was for Bob Rafelson's version of James M. Cain's classic pulp The Postman Always Rings Twice —the definitive portrait of the footloose American go-getter as bum, sexual opportunist, conspirator and killer.

According to Mamet's own account, he "saw the craft of directing as the joyful extension of screenwriting." But he also followed a well-established tradition of eminent writer-directors (Billy Wilder, Preston Sturges, Joseph Mankiewicz, et al), in taking up direction partly in order to protect his own writing. His directorial debut, House of Games , followed closely on the travesty of his play Sexual Perversity in Chicago being filmed (not to his script) as About Last Night (1986). In that same writer-director tradition, Mamet tends to be matter-of-fact to the point of dismissiveness about his own cinematic technique, disclaiming any pretensions to being an auteur. The director's job, he maintains, "is the work of constructing the shot list from the screenplay. The work on the set is nothing. All you have to do on the set is stay awake, follow your plans, help the actors be simple, and keep your sense of humour. The film is directed in the making of the shot list. . . . It is the plan that makes the movie."

"The plan" in more senses than one. In Mamet's films—many of those he has directed, and several that he has written—the action is often set up to deceive the audience, a visual sleight of hand paralleling the scam that's being worked on the characters. In House of Games and The Spanish Prisoner (itself named after a classic con routine), the rug is repeatedly pulled out from under us; just as we think we know what is going on, Mamet reveals a further layer of deception. In Homicide we are led to believe that Joe Mantegna's cop is uncovering a vast anti-Semitic conspiracy, until a supposed Nazi slogan proves to be a brand of pigeon-feed and the whole miasma of suspicion dissolves into nothingness. (Or maybe not, since the film leaves it possible that this revelation is itself just another trick.) Sometimes Mamet enjoys letting us in on the act, as in Things Change , or in his tour de force political satire Wag the Dog where—as if in ironic homage to Baudrillard—a whole war is faked up to hoax the public. Though even here, when we have watched the entire scam being devised, the denouement reveals other dimensions that we were not aware of. Referring to The Spanish Prisoner Mamet oberved: "I don't feel like I created this script—I feel like I've solved it. It's like a magic trick. You have to give people information, but in such a way that they don't realise it is information."

Adapting his own stage work for the screen (as in Oleanna , which he directed, or American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross , which he didn't), Mamet simplifies it without losing its pungent flavour, cutting down on the repetitions and truculent non-sequiturs of the original. "You're basically trying to make up pictures and you only resort to dialogue when you can't make up the perfect picture. . . . The main message is being carried to the audience not by what people say or by how they say it, but by what the camera is doing." Not that the camera, in his view, should do very much: he believes in "let[ting] the cut tell the story," and adds that "fantastic cinematography has been the death of American film." He may well have been thinking of The Untouchables , where Brian De Palma's showy direction jarred with Mamet's taut dialogue. Despite his own outspoken distaste for Hollywood ("Hell with valet parking") and the movie industry, Mamet seems increasingly at ease with filmmaking. In recent years he has shown himself ever more inclined to direct his own scripts—and to adapt and direct the work of other playwrights he admires, such as Terence Rattigan and Samuel Beckett. In the register of Mamet's career his status as screenwriter and director may never rival his towering acclaim as a playwright, but it looks set to run it a very respectable second.

—Philip Kemp

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: