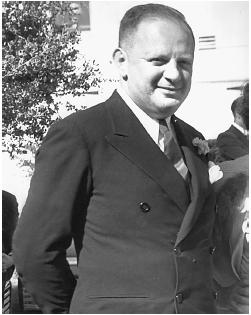

Herman Mankiewicz - Writer

Writer and Producer. Nationality: American. Born: Herman Jacob Mankiewicz in New York City, 7 November 1897; brother of the writer and director Joseph Mankiewicz. Education: Attended Columbia University, New York, graduated; University of Berlin. Family: Married Shulamith Sara Aronson, 1920; one son, the writer Don M. Mankiewicz. Career: 1918—served in the United States Marine Corps; then worked in Europe for the Red Cross Press Service, as publicity manager for Isadora Duncan, and Berlin correspondent for the Chicago Tribune ; 1922–26—assistant drama editor, New York Times ; 1926—first film as writer, The Road to Mandalay , followed in the next dozen years by many films as writer, often as title writer (through the end of the silent period) and script doctor (often uncredited); 1930–32—produced four films, including two Marx Brothers comedies; 1939—began association with the director Orson Welles. Awards: Academy Award for Citizen Kane , 1941. Died: 5 March 1953.

Films as Writer:

- 1926

-

The Road to Mandalay (Browning); Stranded in Paris (Rosson)

- 1927

-

Fashions for Women (Arzner); A Gentleman of Paris (D'Arrast); Figures Don't Lie (Sutherland); The Spotlight (Tuttle); The City Gone Wild (Cruze); The Gay Defender (La Cava); Honeymoon Hate (Reed)

- 1928

-

Two Flaming Youths (Waters); Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (St. Clair); The Last Command (von Sternberg); Love and Learn (Tuttle); A Night of Mystery (Mendes); Abie's Irish Rose (Fleming); Something Always Happens (Tuttle); His Tiger Lady (Henley); The Drag Net (von Sternberg); The Magnificent Flirt (D'Arrast); The Big Killing (Jones); The Water Hole (Jones); The Mating Call (Cruze); Avalanche (Brower); The Barker (Fitzmaurice); Three Weekends (Badger); What a Night! (Sutherland)

- 1929

-

Marquis Preferred (Tuttle); The Canary Murder Case (St. Clair); The Dummy (Milton); The Man I Love (Wellman); Thunderbolt (von Sternberg)

- 1930

-

Men Are Like That (Tuttle); The Love Doctor (Brown); The Mighty (Cromwell); Honey (Ruggles); Ladies Love Brutes (Lee); Love among the Millionaires (Tuttle); The Vagabond King (Berger); True to the Navy (Tuttle)

- 1931

-

The Royal Family of Broadway (Cukor and Gardner); Man of the World (Wallace); Ladies' Man (Mendes)

- 1932

-

The Lost Squadron (Archainbaud); Dancers in the Dark (Burton); Girl Crazy (Seiter)

- 1933

-

Another Language (E. Griffith); Dinner at Eight (Cukor); Meet the Baron (W. Lang)

- 1934

-

The Show-Off (Reisner); Stamboul Quest (Wood)

- 1935

-

After Office Hours (Leonard); Escapade (Leonard)

- 1937

-

John Meade's Woman (Wallace); My Dear Miss Aldrich (Seitz)

- 1939

-

It's a Wonderful World (Van Dyke)

- 1941

-

Keeping Company (Simon); Citizen Kane (Welles); Rise and Shine (Dwan)

- 1942

-

Pride of the Yankees (Wood)

- 1943

-

Stand By for Action (Leonard)

- 1944

-

Christmas Holiday (Siodmak)

- 1945

-

The Enchanted Cottage (Cromwell); The Spanish Main (Borzage)

- 1949

-

A Woman's Secret (Ray)

- 1952

-

The Pride of St. Louis (Jones)

Films as Producer:

- 1930

-

Laughter (D'Arrast)

- 1931

-

Monkey Business (McLeod)

- 1932

-

Horse Feathers (McLeod); Million Dollar Legs (Cline)

- 1933

-

Duck Soup (McCarey)

Publications

By MANKIEWICZ: book—

With Orson Welles, Citizen Kane (script) in The Citizen Kane Book , by Pauline Kael, Boston, Massachusetts, 1971.

On MANKIEWICZ: books—

Meryman, Richard, Mank: The Wit, World, and Life of Herman Mankiewicz , New York, 1978.

Carringer, Robert L., The Making of Citizen Kane , Berkeley, California, 1985.

On MANKIEWICZ: articles—

Film Comment (New York), Winter 1970–71.

Ciment, Michel, "Ouragans autour de Kane," in Positif (Paris), March 1975.

Kilbourne, Don, in American Screenwriters , edited by Robert E. Morsberger, Stephen O. Lesser, and Randall Clark, Detroit, Michigan, 1984.

Film Comment (New York), July-August 1984.

Films in Review (New York), October-November 1984.

Film Dope (Nottingham), December 1987.

Turan, Kenneth, "The Brothers Mankiewicz: A Gold Touch," in the Los Angeles Times , 8 July 1993.

* * *

Lillian Gish once exclaimed, "Yes, Orson Welles is a genius, a genius at self-promotion." That genius for self-promotion, his many talents notwithstanding, was largely responsible for Welles receiving and accepting all credit for the screenplay to Citizen Kane . Despite Welles's statement that "the writer should have the first and last word in filmmaking, the only better alternatives being the writer-director, but with the stress on the first word," he perpetuated the myth that he was solely responsible for the creation of Kane , with utter disregard for the fact that he shared screen credit and the Academy Award with Herman Mankiewicz. Critics and film historians went along with this injustice until 1971 when Pauline Kael exploded the misconception with her controversial essay "Raising Kane ," wherein she set the record straight as to Mankiewicz being the primary contributor to the screenplay. Offensive as this premise was to the auteurists and possibly to Welles, Mankiewicz's contribution to Kane is now an accepted fact, so much so that writers like Richard Corliss can confidently state that "Herman Mankiewicz wrote Citizen Kane with only nominal assistance from Orson Welles."

Why had Mankiewicz's contribution been so ignored for three decades? The two chief reasons were the ego of Orson Welles and the ego of Herman Mankiewicz. Welles's complicity is easy to understand, but who was Herman Mankiewicz? This elder brother of Joseph was a bright, acerbic, hard-drinking bon vivant who began his writing career as a Berlin correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and went on to become a second-string drama editor for the New York Times and a frequent contributor to The New Yorker . He was a familiar face to the Algonquin Round Table set, and Ben Hecht dubbed him "The Central Park West Voltaire." When he went to Hollywood in 1926, he was accused of selling out, but the money was alluring and Mankiewicz had a strong self-destructive and undisciplined streak in him. Screenwriting enhanced his lifestyle, and if one looks at the forty-odd films to which he contributed, there are few clues to foreshadow the excellence of Citizen Kane . A number of his screenplays did carry the reporter/newspaper theme—a milieu he knew very well—and a number of others revealed the wit for which he was well known. The best film for which he received credit was Dinner at Eight , which he wrote in collaboration with Frances Marion. His best writing seems to be for those films on which he was executive producer and for which he took no writing credit— Laughter , Monkey Business , Horse Feathers , Million Dollar Legs , and Duck Soup .

Mankiewicz was a friend of both William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies, and his depiction of them in the Kane script was considered the betrayal of friendship by an alcoholic loser. But personal vendetta aside, Mankiewicz's script is a masterful dissection of power and the fall from grace, and his contribution cannot be overlooked. With that balance in mind, it is fair to concede that while Mankiewicz did write the script, it was Welles's sense of the baroque, his irony, and his entrepreneurial audacity which makes Citizen Kane great cinema.

Mankiewicz's own assessment of screenwriting (circa 1935), while somewhat flippant, is probably closer to the truth than most practitioners would like to admit: "You don't really need to be a writer, in the accepted sense of the word, to write for pictures. Some of the best scenario writers in Hollywood can't write at all. They simply have a flair for ideas, for situations; these, in turn, suggest bits of business; then they tie dialogue onto the business, or hire someone to do it for them. . . . In the movies, for the most part, there is no such thing as individual creation. No one person makes a picture. It is the blend of the work from five to fifteen people—each one of whom is boss of his particular field, each one of whom has to be satisfied. And if it takes ten writers to satisfy the real bosses, what difference does it make, as long as the picture is good." A far cry from Welles, who once pompously opined: "Theatre is a collective experience; cinema is the work of one single person."

—Ronald Bowers

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: