Winsor McCAY - Writer

Animator.

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Winsor Zenis McCay in Spring Lake, Michigan, 26 September 1871.

Education:

Attended Ypsilanti Normal School, Michigan.

Family:

Married Maud Defore, 1891; children: Robert and Marion.

Career:

Before 1889—worked for poster firm, Chicago; 1891—scenic

artist, Vine Street Dime Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio; 1898—reporter

for Cincinnati

Commercial Tribune

, and later for

Enquirer

; 1903—drawings in strip form parodying Kipling's

Just So Stories

attracted attention of James Gordon Bennett, Jr., of

New York Herald

; hired to draw for New York

Evening Telegram

; created strip

Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend

using pseudonym "Silas"; began comic strips for

Herald

; 1905—created

Little Nemo in Slumberland

; 1906—began giving chalk talks on vaudeville circuit;

1908—successful Broadway musical based on

Little Nemo

; 1909—introduced to cartoon animation by J. Stuart Blackton; began

work on

Little Nemo

, first cartoon; 1911—premiered

Little Nemo

in vaudeville act; 1914—used

Gertie the Dinosaur

as part of vaudeville act; 1918—premiere of

The Sinking of the Lusitania

, probably first cartoon feature.

Died:

In 1934.

Films as Director, Writer and Animator:

- 1909

-

Little Nemo (short)

- 1911

-

Winsor McCay

- 1912

-

How a Mosquito Operates ( The Story of a Mosquito ) (short)

- 1914

-

Gertie the Dinosaur ( Gertie the Trained Dinosaur ) (short)

- 1916

-

Winsor McCay and His Jersey Skeeters

- 1918

-

The Sinking of the Lusitania

- 1918–21

-

The Centaurs (short); Flip's Circus (short); Gertie on Tour (short)

- 1921

-

Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend Series; The Pet ; Bug Vaudeville ; Flying House (shorts) (co-d with son Robert McCay)

Publications

On McCAY: book—

Canemaker, John, Winsor McCay: His Life and Art , New York, 1987.

On McCAY: articles—

Canemaker, J., "Winsor McCay," in Film Comment (New York), January-February 1975.

Canemaker, J., "The Birth of Animation," in Millimeter (New York), April 1975.

Cornand, A., "Le Festival d'Annecy et les Rencontres internationales du cinéma d'animation," in Image et Son (Paris), January 1977.

Positif (Paris), no. 355, September 1990.

Marschall, R., "Masters of Comic Strip Art," in American History Illustrated , March-April 1990.

Parsons, Scott, "Animation Legend: Winsor McCay," in Library Journal , 15 September 1994.

Blonder, R., "Mosquitoes, Dinosaurs, and the Image-ination," in Animatrix (Los Angeles), no. 8, 1994–1995.

Filmvilag (Budapest), no. 8, 1996.

Blackmore, Tim, "McCay's Mechanical Muse: Engineering Comic-Strip Dreams," in Journal of Popular Culture , Summer 1998.

* * *

Winsor McCay is generally regarded as the first American auteur of animation. Although not the first to experiment with animated films, McCay achieved artistic and technical heights that established animation as a viable form and that set ground rules for a style of pictorial illusionism and closed figurative forms in American animated cartoons.

McCay studied art and worked as an illustrator and sign painter before settling down in 1889 as a newspaper cartoonist in Cincinnati. His success as a cartoonist led him to move in 1903 to the New York Evening Telegram . There he worked as a staff illustrator and developed the comic strips that brought him international fame.

During the next several years, McCay created such comic strips as Hungry Henrietta , Little Sammy Sneeze , Dream of the Rarebit Fiend , Pilgram's Progress , and his most famous work, Little Nemo in Slumberland. Little Nemo , which ran from 1905 to 1911, is the pinnacle of comic strip art in the first decade of the 20th century. It displays an unparalleled application of Art Nouveau graphic style, translating sinewy, irregular forms and rhythms into a delightfully decorative comic strip design. The strips related the fantastic adventures which befell the child Little Nemo, who always woke up in the last panel of the comic strip.

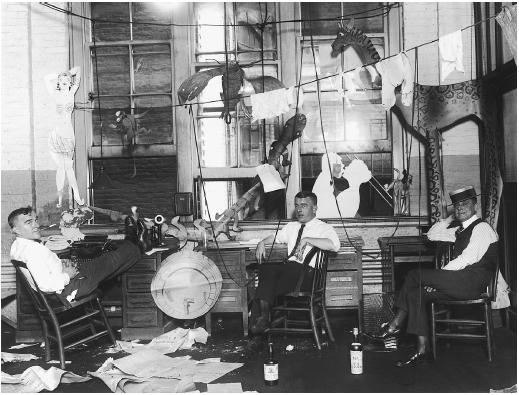

Sometime about 1909, McCay set to work on making an animated film of Little Nemo in Slumberland . (He credits his son's interest in flip books as the source of inspiration for his cinematic experiment.) After drawing and hand-coloring more than 4,000 detailed images on rice paper, McCay employed his animated film in his vaudeville act while Vitagraph, the company that shot and produced the film, simultaneously announced its release of Little Nemo . The animation did not employ a story but rather showed the characters of the comic strip continuously moving, stretching, flipping, and metamorphosing. McCay used foreshortening and exact perspective to create depth and an illusionistic sense of space even without the aid of any background. The animation sequence is framed by a live-action story in which McCay's friends scoff at the idea that he can make moving pictures and then congratulate him when he succeeds.

The advertisements and the prologue for the film stressed the monumental amount of labor and time required to do the drawings. McCay promoted and flaunted not only his role as an artist but the animator's "trade secrets." Throughout his career, McCay emphasized the revelation of the mechanics and process of animation, a self-reflexive approach that grew naturally out of the way he self-consciously undermined conventions of comic strip art and constantly called attention to the form itself.

McCay made his second animated cartoon in 1911–12. How a Mosquito Operates relies on a simpler, less intricately graphic style in order to tell the story of a large mosquito's encounter with a sleeping victim. Two years later, McCay completed the animated film for which he is most famous, Gertie the Dinosaur . Like his previous two films, McCay incorporated the cartoon into his vaudeville act and, like Little Nemo , Gertie's animation is framed by a live-action sequence. But in Gertie , McCay combined the lessons of his earlier two films in order to create a character who is animation's first cartoon personality.

After Gertie the Dinosaur , McCay continued doing other animated cartoons but began utilizing celluloid (instead of rice paper) and stationary backgrounds that did not have to be redrawn for every frame. He also devised a system of attaching pre-punched sheets to pegs so that he could eliminate the slight shifting that occurred from drawing to drawing. His discovery represents the first instance of peg registration, a technique commonly employed in modern animation.

Although McCay's later cartoons were popular and praised for their naturalness ( Centaurs and Sinking of the Lusitania ), McCay's elaborate full animation proved too time-consuming and costly to inspire others, more concerned with production, to adhere to his high standards. Neither a full-time animator nor part of a movie studio, McCay was free to pursue his own ends. His success is due to his ability to translate graphic style to animation as well as to his gregarious showmanship.

McCay stopped making animated films in 1921, and by the time he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934, his contribution as an animator was almost forgotten. Only in the 1960s was McCay rediscovered as an American artist. In 1966, New York's Metropolitan Museum sponsored an exhibit of his work.

—Lauren Rabinovitz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: