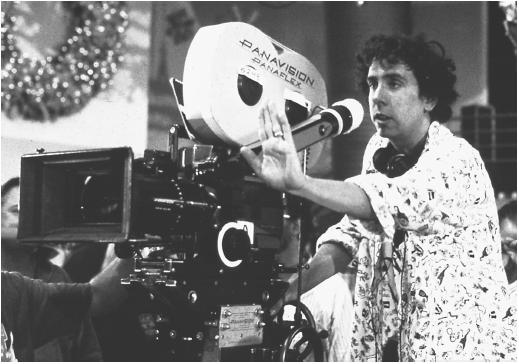

Tim Burton - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Burbank, California, 1958.

Education:

Studied animation at California Institute of Arts, B.A., 1981.

Family:

Married Lena Gieseke, February 1989 (divorced).

Career:

Cartoonist since grade school in Burbank; animator, Walt Disney Studios,

Hollywood, California, 1981–85; director and producer of feature

films, 1985—.

Awards:

Chicago Film Festival Award, for

Vincent

, 1982

;

ShoWest Award, for Director of the Year, 1990; Emmy Award (with others)

for outstanding animated program, for

Beetlejuice

, 1990.

Agent:

Creative Artists Agency, 9830 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills, California,

90212.

Films as Director:

- 1982

-

Vincent (animated short); Frankenweenie (live-action short)

- 1985

-

Pee-Wee's Big Adventure

- 1988

-

Beetlejuice

- 1989

-

Batman

- 1990

-

Edward Scissorhands (+ co-sc, pr)

- 1992

-

Batman Returns (+ co-pr)

- 1994

-

Ed Wood (+ co-pr)

- 1995

-

Mars Attacks! (+ co-pr, co-sc)

- 1999

-

Sleepy Hollow

Other Films:

- 1992

-

Singles (role)

- 1993

-

Tim Burton's The Nightmare before Christmas (co-sc, co-pr, des)

- 1994

-

Cabin Boy (co-pr); A Century of Cinema (Caroline Thomas) (as himself)

- 1995

-

Batman Forever (exec pr)

Publications

By BURTON: books—

The Nightmare before Christmas (for children), New York, 1993.

My Art and Films , New York, 1993.

With Mark Salisbury, Burton on Burton , New York, 1995.

Burton (for children), New York, 2000.

By BURTON: articles—

Interviews, in Los Angeles Times , 12 August 1990; 7 December 1990; 12 March 1992; 14 June 1992.

Interview, in Washington Post , 16 December 1990.

"Slice of Life," an interview with Brian Case, in Time Out (London), 19 June 1991.

"Introduction," in Matthew Rolston, Big Pictures , Boston, 1991.

Interviews, in Chicago Tribune , 14 June 1992; 28 June 1992.

Interview, in Vogue , July 1992.

"Punching Holes in Reality," an interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment , November/December 1994.

"Space Probe," an interview with Nigel Floyd, in Time Out (London), 19 February 1997.

Interview with Christian Viviani and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), March 1997.

Bondy, J.A., "Intervju," in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol 30. no. 2, 1997.

Article in Andrew Kevin Walker, The Art of Sleepy Hollow , New York, 2000(?).

On BURTON: book—

Hanke, Ken, Tim Burton: An Unauthorized Biography of the Filmmaker , Los Angeles, 1999.

On BURTON: articles—

Corliss, Richard, "A Sweet and Scary Treat: The Nightmare before Christmas ," in Time , 11 October 1993.

Thompson, Caroline, "On Tim Burton," in New Yorker , 21 March 1994.

Maio, Kathi, "Sick Puppy Auteur?," in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction , May 1994.

Krohn, Bill, "Tim Burton, de Disney à Ed Wood," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1994.

Positif (Paris), June 1995.

Jean, Marcel, "Les effets d'une épidémie," in 24 Images (Montreal), December-January 1995–1996.

Jean, Marcel, "Carnet de notes sur le corps martien," in 24 Images (Montreal), Spring 1997.

Knuutila, P., "Tim Burton," in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 39, no. 2, 1997.

* * *

Although in the last resort I find his work more distinctive than distinguished, Tim Burton compels interest and attention by the way in which he has established within the Hollywood mainstream a cinema that is, to say the least, highly eccentric, idiosyncratic, and personal.

Burton's cinema is centered firmly on the figure of what I shall call (for want of a better term, and knowing that this one is now "politically incorrect") the freak. I define this as a person existing quite outside the bounds of the conventional notion of normality, usually (but not exclusively, as I include Burton's Ed Wood in this) because of some extreme physical peculiarity. Every one of the films, without exception, is built around at least one freak. One must then subdivide them into two categories: the "positive" freaks, who at least mean well, and the "negative" freaks, who are openly malignant. In the former category, in order of appearance: Pee-Wee Herman ( Pee-Wee's Big Adventure ), Edward Scissorhands, Catwoman ( Batman Returns ), Jack ( The Nightmare before Christmas ), Ed Wood; in the latter, the Joker ( Batman ) and the Penguin ( Batman Returns ). Beetlejuice (or "Betelgeuse") belongs ambiguously to both categories, though predominantly to the latter; to which one might also add, without stretching things too far, Riddler and Two-Face from Batman Forever —watered-down Burton, produced by him but written and directed by others, still owing a great deal to his influence. If one leaves aside Pee-Wee's Big Adventure and The Nightmare before Christmas (which Burton conceived and produced but did not direct), this gives us an alternative but exactly parallel division: three films

Of the malignant freaks, Danny de Vito's Penguin is at once the most grotesque (to the verge of unwatchability) and the only one with an excuse for his malignancy: unlike the others he was born a freak, cast out and presumed to die by his parents, surviving by chance. The Joker and (if one permits the inclusion) Two-Face are physical freaks because of disfigurement, but this has merely intensified a malignancy already there. They are colorful and vivid, but not especially interesting: they merely embody a somewhat simplistic notion of evil, the worked-up energy of the over-the-top performances a means of concealing the essential emptiness at the conceptual level.

The benign freaks are more interesting. They are invariably associated with creativity: Pee-Wee, Edward Scissorhands, and Ed Wood are all artists, of a kind every bit as idiosyncratic as their creator's. This is set, obviously, against the determined destructiveness of the malignant freaks, who include in this respect Beetlejuice: the film's sympathetic characters (notably Winona Ryder) may find him necessary at times, but his dominant characteristic is a delight in destruction for its own sake. What gives the positive freaks (especially those played by Johnny Depp) an extra dimension is their extreme fragileness and vulnerability (the negative freaks always regard themselves, however misguidedly, as invincible).

Credit must be given to Burton's originality and inventiveness: he is an authentic artist in the sense that he is so clearly personally involved in and committed to his peculiar vision and its realization in film. What equally demands to be questioned is the degree of real intelligence underlying these qualities. The inventiveness is all on the surface, in the art direction, makeup, special effects. The conceptual level of the films does not bear very close scrutiny. The problem is there already, and in a magnified form, in Beetlejuice: the proliferation of invention is too grotesque and ugly to be funny, too wild, arbitrary, and unselfcritical to reward any serious analysis. The two Batman movies are distinguished by the remarkably dark vision (in a film one might expect to be "family entertainment") of contemporary urban/industrial civilization. But Michael Keaton's Batman, while unusually and mercifully restrained, fails to make any strong impression, and one is thrown back on the freaks who, with one notable exception, quickly outstay their welcome. The exception is Michelle Pfeiffer's Catwoman (in Batman Returns ), and that is due primarily to one of the great screen presences of our time. Burton's overall project (in his work as a whole) seems to be to set his freaks (both positive and negative) against "normality" in order to show that normality, today, is every bit as weird: a laudable enough project, most evident in Edward Scissorhands. But the depiction of normality in that film (here, small-town suburbia) amounts to no more than amiable, simple-minded parody (despite the charm of Dianne Wiest's Avon Lady, but her role dwindles as the film proceeds). For all the grotesquerie of his monsters, Burton's cinema is ultimately too soft-centered, lacking in rigor and real thinking. Ed Wood , however, may be taken as evidence that Burton is beginning to transcend the limitations of his previous work: it is far and away his most satisfying film to date. Here is surely one of cinema's most touching celebrations of the sheer joy of creativity with the irony, of course, that it is manifested in an "artist" of no talent whatever. Johnny Depp, in what is surely, with Pfeiffer's Catwoman, one of the two most complex and fully realized incarnations in Burton's work, magically conveys his character's absolute belief in the value of his own creations and his own personal joy and excitement in creating them, never realizing that they will indeed go down in film history as topping everyone's list of the worst films ever made. Yet his Ed Wood never strikes us as merely stupid: simply as a man completely caught up in his own delight in creative activity—always longing for recognition, but never self-serving or mercenary. This self-delusion, at once marvelous and pathetic, goes hand in hand with his growing compassion for and commitment to the decrepit and drug-addicted Bela Lugosi (Martin Landau, in a performance that, for once, fully deserved its Oscar), and his equally delusory conviction that Lugosi is still a great star.

Burton's two recent films, Mars Attacks! and Sleepy Hollow , neatly illustrate, respectively, his weaknesses and strengths. Mars Attacks! , a parody both of Independence Day and the science fiction invasion cycle of the 1950s, opens promisingly, apparently initiating a mordant satire on contemporary American civilization, the Martians' approach to Earth, and the possibility that they represent a more advanced and enlightened culture producing a cross-section of possible reactions from a wide range of cultural positions, presented as variously vacuous, irrelevant, or self-serving. From the point where the Martians turn out to be, after all, stereotypically malevolent, within any redeeming features whatever, all that is lost: the film has nowhere to go, and disintegrates into a series of obvious gags ranging from the gratuitously ugly and grotesque (the fates of Pierce Brosnan and Sarah Jessica Parker) to the merely childish.

Sleepy Hollow is built around the talent and persona of Johnny Depp, star of the two most distinguished of Burton's previous films (which can scarcely be coincidental). Once again, the collaboration with Depp brings out all Burton's finest qualities, an aesthetic and emotional sensibility totally absent from the majority of his work. The film's horrors are grotesque but never offered as funny, becoming a perfect foil for Depp's essential gentleness, elegance, and underlying strength. The art direction shows Burton and his designer at their finest, creating effects that are at once frightening, beautiful, and authentically strange. It seems clear that Tim Burton needs Johnny Depp more than Johnny Depp needs Tim Burton.

—Robin Wood

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: