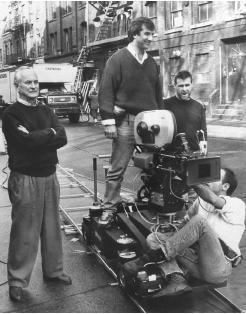

James Ivory - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Berkeley, California, 7 June 1928. Education: Educated in architecture and fine arts, University of Oregon; studied filmmaking at University of Southern California, M.A. 1956. Family: Life companion of the producer Ismail Merchant. Military Service: Corporal in U.S. Army Special Services, 1953–55. Career: Founder and partner, Merchant-Ivory Productions, New York, 1961; directed his first feature, The Householder , and also began his collaboration with writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, 1963. Awards: Best Foreign Film French Academie du Cinema, and prize at Berlin Festival, for Shakespeare Wallah , 1968; Guggenheim Fellow, 1973; Best Film British Academy Award, for A Room with a View , 1987; Silver Lion, Venice Festival, for Maurice , 1987; Best Film British Academy Award, National Board of Review Best Director, Cannes Film Festival 45th Anniversary Prize, Bodil Festival Best European Film, for Howards End , 1992; John Cassavetes Award Independent Spirit Award, 1993; London Critics Circle Director of the Year, Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists Best Director-Foreign Film, Robert Festival Best Foreign Film, for The Remains of the Day, 1993; Directors Guild of America Lifetime Achievement Award, 1995. Address: c/o Merchant-Ivory Productions, Ltd., 250 W. 57th St., Suite 1913-A, New York, NY 10107, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1957

-

Venice: Themes and Variations (doc) (+ sc, ph)

- 1959

-

The Sword and the Flute (doc) (+ sc, ph, ed)

- 1963

-

The Householder

- 1964

-

The Delhi Way (doc) (+ sc)

- 1965

-

Shakespeare Wallah (+ co-sc)

- 1968

-

The Guru (+ co-sc)

- 1970

-

Bombay Talkie (+ co-sc)

- 1971

-

Adventures of a Brown Man in Search of Civilization (doc)

- 1972

-

Savages (+ pr, sc)

- 1974

-

The Wild Party

- 1975

-

Autobiography of a Princess

- 1977

-

Roseland

- 1979

-

Hullabaloo over Georgie and Bonnie's Pictures ; The Europeans (+ pr, co-sc, role as man in warehouse)

- 1980

-

Jane Austen in Manhattan

- 1981

-

Quartet (+ co-sc)

- 1982

-

Courtesans of Bombay (doc) (+ co-sc)

- 1983

-

Heat and Dust

- 1984

-

The Bostonians

- 1986

-

A Room with a View

- 1987

-

Maurice (+ co-sc)

- 1989

-

Slaves of New York

- 1990

-

Mr. and Mrs. Bridge

- 1992

-

Howards End

- 1993

-

The Remains of the Day

- 1995

-

Jefferson in Paris ; Lumiere and Company (co-d)

- 1996

-

Surviving Picasso

- 1998

-

A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries (+ co-sc)

- 2000

-

The Golden Bowl

Other Films:

- 1985

-

Noon Wine (Fields) (co-exec pr)

Publications

By IVORY: books—

Savages , with Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, New York, 1973.

Shakespeare Wallah: A Film , with Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, New York, 1973.

Autobiography of a Princess: Also Being the Adventures of an American Film Director in the Land of the Maharajas , New York, 1975.

By IVORY: articles—

" Savages ," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1971.

Interviews with Judith Trojan, in Take One (Montreal), January/February 1974 and May 1975.

Interview with D. Eisenberg, in Inter/View (New York), January 1975.

Interview with P. Anderson, in Films in Review (New York), October 1984.

"The Trouble with Olive," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1985.

"Dialogue on Film: James Ivory," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), January/February 1987.

Interviews in Hollywood Reporter , 31 March and 6 May 1989.

"Arachnophobia," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1990.

Interview with G. Fuller in Interview (New York), November 1990.

On IVORY: books—

Pym, John, The Wandering Company: Twenty-one Years of Merchant-Ivory Films , London, 1983.

Martini, Emanuela, James Ivory , Bergamo, 1985.

Long, Robert Emmett, The Films of Merchant-Ivory , New York, 1991.

On IVORY: articles—

Gillett, John, "Merchant-Ivory," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1973.

Gillett, John, "A Princess in London," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1974.

Hillgartner, D., "The Making of Roseland ," in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), January 1978.

" Quartet Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 1 October 1981.

McFarlane, Brian, "Some of James Ivory's later films," in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), June 1982.

Firstenberg, J.P., "A Class Act Turns Twenty-five," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), September 1987.

Monthly Film Bulletin (London), November 1987.

Harmetz, Aljean, "Partnerships Make a Movie," in New York Times , 18 February 1990.

"Is Good Taste Enough? The Gorgeous Films of Merchant-Ivory," in The Economist (London), 29 February 1992.

Hirshey, G., "A Team with a View," in Gentlemen's Quarterly (New York), March 1992.

Dudar, Helen, "In the Beginning, the Word; At the End, the Movie," in New York Times , 8 March 1992.

Maslin, Janet, "Finding Realities to Fit a Film's Illusions," in New York Times , 12 March 1992.

Corliss, Richard, "Doing It Right the Hard Way," in Time (New York), 16 March 1992.

Lyons, D., "Tradition of Quality," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1992.

Eller, C., "Merchant Ivory Links with Disney," in Variety (New York), 27 July 1992.

Ash, J., "Stick It up Howard's End," in Gentlemen's Quarterly (New York), August 1994.

* * *

The work of James Ivory was a fixture in independent filmmaking of the late 1960s and 1970s. Roseland , for example, Ivory's omnibus film about the habitués of a decaying New York dance palace, garnered a standing ovation at its New York Film Festival premiere in 1977, and received much critical attention afterward. However, it was not until A Room with a View , Ivory's stately adaptation of E. M. Forster's novel, that the filmmaker gained full international recognition. The name-making films he directed earlier in the 1980s—which included adaptations of two Forster works and two Henry James novels—inextricably linked Ivory with the contemporary British cinema's tradition of urbane, even ultra-genteel, costume dramas.

Ivory's independence, his influential involvement with English film, and his sustained collaborative partnership with producer Ismail Merchant invite comparisons with an earlier pairing in British cinema, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Both teams have found themselves attracted to material dealing with the effects of sexual repression or with the clash of differing cultures, as in, for example, Black Narcissus (Powell/Pressburger, 1947), The Europeans (Ivory/Merchant, 1979), and A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries (Ivory/Merchant, 1998). While Powell and Pressburger worked with various forms of visual experimentation, employing heightened colors, frequently moving cameras, and cinematographic juxtaposition to achieve an opulent, metaphorical visual texture, Ivory's work represents a distinct retrenchment, a withdrawal from visual hyperbole, a comparative conservatism of visual style. An example of one of Ivory's few attempts at visual expressionism (a moment in his work that seems directly inspired by Powell, in fact) illustrates this point. In The Bostonians , Ivory attempts to express Olive Chancellor's hysteria by using stylized colors and superimposition in isolated dream sequences. Because the film's style is deeply rooted in naturalism, unlike that of Powell, the sequences look stilted and awkward, remarkably out of place in the context of the film.

The naturalism of Ivory's style often perfectly complements the director's interest in the dynamics of isolated communities: the drama troupe in Shakespeare Wallah , for example, or the dancers in Roseland , or the members of the New York downtown-punk scene in Slaves of New York. Ivory's films characteristically trace the formation of community around a common interest—or, more often, a common flaw or a shared loss—and his powers of observation are enlivened by attention to minute details of gesture and a keen sympathy for marginal characters. It is this sympathy that attracts him to works such as Evan Connell's novels Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge. Ivory thus provides a densely ironic but ultimately sympathetic portrait of the quietly desperate middle-class lives of the Bridges in Kansas City. This sympathy accounts as well for Ivory's handling of characters such as Charlotte Bartlett in A Room with a View. In Forster's novel, Miss Bartlett is lampooned tirelessly, emerging as one of the novel's chief examples of English hypocrisy and Forster's conception of high culture as the poison of the spirit—this is in spite of a half-hearted reprieve for the character in the novel's last pages. In the film, Maggie Smith's agile, witty performance makes the character far more appealing, and Ivory's treatment of the character (he cuts from the lovers' final union to shots of Miss Bartlett's soundless, unbending loneliness) shows that he clearly interprets her as a fully sympathetic character of great pathos.

Ivory's two Forster adaptations, A Room with a View and Maurice , are among the high-water marks of his career through the 1980s. These two films do more than demonstrate Ivory's often bracingly literary sensibility (most of Ivory's films are adaptations that doggedly strive for extreme "faithfulness" to their source material): In the Forster adaptations, this "faithfulness" co-exists with crucial shifts of emphasis that provide, simultaneously, modern interpretations of the texts.

An example of this occurs in the scene of the murder in the square in A Room with a View. In its use of hand-held cameras, graphic matches, and rhythmic editing, which provides mercurial shifts in the tone of the sequence from gravity to exultation, the sequence becomes one of the film's set-pieces, supplying the complexities that Forster largely avoids in his comparatively laconic treatment of the scene.

Upon its release in 1992, Howards End was justifiably hailed as the best film ever in the long and distinguished collaboration of Ivory, Merchant, and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. This stylish work is yet another adaptation of an E. M. Forster novel. Its scenario examines a popular Ivory theme, as it explores the repercussions of social classes coming together at a specific point in recent history (in this case, at the close of the Edwardian era in England). Emma Thompson is altogether brilliant in the role that solidified her career. She plays a cheeky and individualistic young woman who does not come from a monied background, and who is slyly charmed by a prosperous gentleman (Anthony Hopkins) whose upper-class facade hides a deceitful and heartless disposition.

The Remains of the Day is nearly as fine a film as Howards End. Based on the acclaimed novel by Kazuo Ishiguro, the scenario dissects the personality of an ideal servant: Stevens (Hopkins), a reserved British butler who is singlemindedly dedicated to his employer, Lord Darlington (James Fox). The time is between the World Wars—and no matter that the misguided Darlington is perilously flirting with Nazism, and that Miss Kenton (Thompson), the new housekeeper, might be a potential romantic partner for Stevens. The servant is steadfastly absorbed in his professional role, to the exclusion of all else. He knows only to suppress his needs, feelings, and desires, all in the name of service to his master. The Remains of the Day essentially is a character study of Stevens, who is superbly played by the ever-reliable Hopkins. It is yet one more in a line of Ivory's meticulous period dramas.

The mid-to-late 1990s found Ivory exploring the lives of revered historical figures. Jefferson in Paris concerns the American Thomas Jefferson, one of the nation's founding fathers, shown here as the U.S. Ambassador to France. However, the film is several shades below the best of the previous Ivory-Merchant-Jhabvala collaborations. While Jefferson in Paris exquisitely captures a time and place, the level of detail in the film renders the narrative all too episodic. Still, Ivory offers a full-bodied portrayal of Jefferson (Nick Nolte), while depicting a range of his personal and political involvements. Most intriguing of all is the paradox of Jefferson's disgust with the overindulgences of the French aristocracy combined with his agonized collusion in keeping the status quo with regard to the maintenance of slavery as an American "institution." In Jefferson in Paris , Ivory yet again examines the theme of class differences, exploring the invisible walls that separate those classes. Only here, class is measured by the color of one's skin. Even though individuals share the same bloodlines because of sexual liaisons between master and slave, those with black skin are enslaved by those with white skin. Ivory portrays the widowed Jefferson falling in love with a married woman (Greta Scacchi) and having a sexual tryst with Sally Hemings (Thandie Newton), an adolescent slave. It remains uncertain if the latter affair ever happened. For this reason, Jefferson in Paris was the subject of debate and controversy among Jeffersonian scholars.

Ivory's next film, Surviving Picasso, charts the relationship between Pablo Picasso (Anthony Hopkins) and Francoise Gilot (Natascha McElhone), a young artist who is several decades his junior. Here, the genius of Picasso is obscured by his all-encompassing cruelty and misogyny. Gilot believes she has the backbone to maintain her individuality while sharing Picasso's bed, and for ten years she gives it the old college try before finally leaving him. Although vividly played by Hopkins, Picasso is never more than a womanizing caricature; there is little insight into why he is who he is, let alone what made him one of the giants of 20th-century art.

Ivory fared somewhat better with A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries , based on the autobiographical novel by Kaylie (the daughter of James) Jones. A Soldier's Daughter is the story of an internationally acclaimed expatriate novelist (Kris Kristofferson) and his familial bonds, with the scenario emphasizing his relationship with his daughter (Leelee Sobieski) as she matures from girlhood to young womanhood. At the outset, the family resides in Paris, with a spotlight on the impact of American pop culture on post-war Europe. Then the clan resettles in the United States, where the children are viewed by their schoolmates as "frogs" and are alienated from their surroundings.

The opening section of A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries is slight and episodic; however, its finale, which centers on the writer's death, is a knowing exploration of what it means to love, and then lose, a husband and a father. One of the dramatic highlights occurs after the writer's demise, when his widow (Barbara Hershey) recalls their courting and mourns her loss.

Despite its flaws, A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries is a heartfelt portrait of a loving, non-dysfunctional family—a rarity in contemporary cinema.

—James Morrison, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: