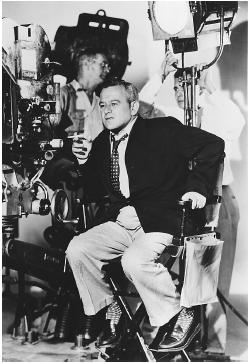

William Wyler - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Willy Wyler in Mulhouse (Mülhausen), Alsace-Lorraine, 1 July 1902; became U.S. citizen, 1928. Family: Married 1) Margaret Sullavan, 1934 (divorced 1936); 2) Margaret Tallichet, 1938, four children. Military Service: U.S. Army Air Corps, 1942–45; major. Career: Travelled to America at invitation of cousin Carl Laemmle, 1920; worked in publicity department for

Films as Director:

- 1925

-

Crook Buster

- 1926

-

The Gunless Bad Man ; Ridin' for Love ; Fire Barrier ; Don't Shoot ; The Pinnacle Rider ; Martin of the Mounted ; Lazy Lightning ; Stolen Ranch

- 1927

-

Two Fister ; Kelly Gets His Man ; Tenderfoot Courage ; The Silent Partner ; Galloping Justice ; The Haunted Homestead ; The Lone Star ; The Ore Riders ; The Home Trail ; Gun Justice ; Phantom Outlaw ; Square Shooter ; The Horse Trader ; Daze in the West ; Blazing Days ; Hard Fists ; The Border Cavalier ; Straight Shootin' ; Desert Dust

- 1928

-

Thunder Riders ; Anybody Here Seen Kelly

- 1929

-

The Shakedown ; The Love Trap

- 1930

-

Hell's Heroes ; The Storm

- 1931

-

A House Divided

- 1932

-

Tom Brown of Culver

- 1933

-

Her First Mate ; Counselor at Law

- 1934

-

Glamour ; The Gay Deception

- 1936

-

These Three ; Dodsworth ; Come and Get It

- 1937

-

Dead End

- 1938

-

Jezebel

- 1939

-

Wuthering Heights

- 1940

-

The Westerner ; The Letter

- 1941

-

The Little Foxes

- 1942

-

Mrs. Miniver

- 1944

-

Memphis Belle

- 1946

-

The Best Years of Our Lives

- 1947

-

Thunder-Bolt

- 1949

-

The Heiress

- 1951

-

Detective Story

- 1952

-

Carrie

- 1953

-

Roman Holiday

- 1955

-

The Desperate Hours

- 1956

-

Friendly Persuasion

- 1958

-

The Big Country

- 1959

-

Ben-Hur

- 1962

-

The Children's Hour

- 1965

-

The Collector

- 1966

-

How to Steal a Million

- 1968

-

Funny Girl

- 1970

-

The Liberation of L.B. Jones

Publications

By WYLER: articles—

"William Wyler: Director with a Passion and a Craft," with Hermine Isaacs, in Theater Arts (New York), February 1947.

"Interview at Cannes," in Cinema (Beverly Hills), July/August 1965.

Interview with Charles Higham, in Action (Los Angeles), September/October 1973.

"Wyler on Wyler," with Alan Cartnel, in Inter/View (New York), March 1974.

"Dialogue on Film," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1976.

"No Magic Wand," in Hollywood Directors: 1941–76 , edited by Richard Koszarski, New York, 1977.

Interview with P. Carcassonne and J. Fieschi, in Cinématographe (Paris), March/April 1981.

Lecture excerpts in Films and Filming (London), October 1981.

On WYLER: books—

Drinkwater, John, The Life and Adventures of Carl Laemmle , New York, 1930.

Griffith, Richard, Samuel Goldwyn: The Producer and His Films , New York, 1956.

Reisz, Karel, editor, William Wyler, an Index , London, 1958.

Madsen, Axel, William Wyler , New York, 1973.

Kolodiazhnaia, V., Uil'iam Uailer , Moscow, 1975.

Anderegg, Michael A., William Wyler , Boston, 1979.

Kern, Sharon, William Wyler: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1984.

Fink, Guido, William Wyler , Florence, 1989.

On WYLER: articles—

Griffith, Richard, "Wyler, Wellman, and Huston," in Films in Review (New York), February 1950.

Reisz, Karel, "The Later Films of William Wyler," in Sequence (London), no. 13, 1951.

"Personality of the Month," in Films and Filming (London), July 1957.

Heston, Charlton, "The Questions No One Asks about Willy," in Films and Filming (London), August 1958.

Reid, John Howard, "A Little Larger than Life," in Films and Filming (London), February 1960.

Reid, John Howard, "A Comparison of Size," in Films and Filming (London), March 1960.

Sarris, Andrew, "Fallen Idols," in Film Culture (New York), Spring 1963.

Brownlow, Kevin, "The Early Days of William Wyler," in Film (London), Autumn 1963.

Heston, Charlton, "Working with William Wyler," in Action (Los Angeles), January/February 1967.

Hanson, Curtis, "William Wyler," in Cinema (Beverly Hills), Summer 1967.

Carey, Gary, "The Lady and the Director: Bette Davis and William Wyler," in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1970.

Doeckel, Ken, "William Wyler," in Films in Review (New York), October 1971.

Higham, Charles, "William Wyler," in Action (Los Angeles), September/October 1973.

Phillips, Gene, "William Wyler," in Focus on Film (London), Spring 1976.

Heston, Charlton, "The Ben-Hur Journal," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1976.

Swindell, Larry, "A Life in Film," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1976.

Renaud, T., "William Wyler: 'L'Homme qui ne fit pas jamais un mauvais film,"' in Cinéma (Paris), September 1981.

On WYLER: film—

Directed by William Wyler (Slesin), 1986.

* * *

William Wyler's career is an excellent argument for nepotism. Wyler went to work for "Uncle" Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal, and learned the movie business as assistant director and then director of programmers, mainly westerns. One of his first important features, A House Divided , demonstrates many of the qualities that mark his films through the next decades. A transparent imitation of Eugene O'Neill's Desire under the Elms , it contains evidence of the staging strategies that identify Wyler's distinctive mise-en-scène . The film's premise holds particular appeal for a director who sees drama in claustrophobic interiors, the actors held in expressive tension by their shifting spatial relationships to each other, the decor, and the camera. In A House Divided Wyler extracts that tension from the dynamics implicit in the film's principal set: the downstairs room that confines the crippled father (Walter Huston) and the stairs leading to the landing between the rooms of the son (Kent Douglass) and the young stepmother (Helen Chandler). The stairway configuration is favored by Wyler for the opportunity it gives him to stack the agents of the drama and to fill the frame both vertically and in depth. When he later collaborates with cinematographer Gregg Toland, the potential of that depth and height is enhanced through the use of varying degrees of hard and soft focus. (Many critics, who are certainly unfamiliar with Wyler's early work, have unjustly credited Toland for the depth of staging that characterizes the partnership.)

The implications of focus in Wyler's stylistics go far beyond lighting procedures, lenses, or even staging itself. Focus directs the viewer's attention to varieties of information within the field, whatever its shape or extent. Focus gives simultaneous access to discordant planes, characters, and objects that challenge us to achieve a full, fluctuating reading of phenomena. André Bazin, in his important essay on Wyler in the French edition of What Is Cinema? , speaks of the director's "democratic" vision, his way of taking in the wholeness of a field in the unbroken time and space of the " planséquence ," a shot whose duration and complexity of staging goes far beyond the measure of the conventional shot. Bazin opposes this to the analytic montage of Soviet editing. In doing so he perhaps underestimates the kind of control that Wyler's deep field staging exerts upon the viewer, but he does suggest the richness of the visual text in Wyler's major films.

Counselor at Law is a significant test of Wyler's staging. The Broadway origins of the property are not disguised in the film; instead, they are made into a virtue. The movement through the law firm's outer office, reception room, and private spaces reflects a fluidity that is a function of the camera's mobility and a challenge to the fixed frame of the proscenium. Wyler's tour de force rivals that of the film's star, John Barrymore. Director and actor animate the attorney's personal and professional activities in a hectic, ongoing present, sweeping freely through the sharply delineated (and therefore sharply perceived) vectors of the cinematic/theatrical space.

Wyler's meticulousness and Samuel Goldwyn's insistence on quality productions resulted in the series of films, often adaptations of prestigious plays, that most fully represent the director's method. In Dodsworth , the erosion of a marriage is captured in the opening of the bedroom door that separates husband and wife; the staircase of These Three delimits the public and private spaces of a film about rumor and intimacy; the elaborate street set of Dead End is examined from a dizzying variety of camera angles that create a geometry of urban life; the intensity of The Little Foxes is sustained through the focal distances that chart the shape of family ties and hatreds.

After the war, the partnership of Wyler and Toland is crowned by The Best Years of Our Lives , a film whose subject (the situation of returning servicemen) is particularly pertinent, and whose structure and staging are the most personal in the director's canon.

In his tireless search for the perfect shot, Wyler was known as the scourge of performers, pushing them through countless retakes and repetitions of the same gesture. Since performance in his films is not pieced together in the editing room but is developed in complex blockings and shots of long duration, Wyler required a high degree of concentration on the part of the actors. Laurence Olivier, who was disdainful of the medium prior to his work in Wuthering Heights , credits Wyler for having revealed to him the possibilities of the movies. But it is Bette Davis who defines the place of the star actor in a Wyler film. The three projects she did with Wyler demonstrate how her particular energies both organize the highly controlled mise-enscène and are contained within it. For Jezebel she won her second Academy Award. In The Letter , an exercise in directorial tyranny over the placement of seemingly every element in its highly charged frames, the viewer senses a total correspondence between the focus exercised by director and performer.

During the last decades of Wyler's career, many of the director's gifts, which flourished in contexts of extreme dramatic tension and the exigencies of studio shooting, were dissipated in excessively grandiose properties and "locations." There were, however, exceptions. Wyler's presence is strongly felt in the narrow staircase of The Heiress and the dingy station house of Detective Story. He even manages to make the final shootout of The Big Country adhere to the narrowest of gulches, thereby reducing the dimensions of the title to his familiar focal points. But the epic scope of Ben Hur and the ego of Barbra Streisand (in Funny Girl ) escape the compact economies of the director's boxed-in stackings and plane juxtapositions. Only in The Collector , a film that seems to define enclosure (a woman is kept prisoner in a cellar for most of its duration) does Wyler find a congenial property. In it he proves again that the real expanse of cinema is measured by its frames.

—Charles Affron

The first is that George C. Scott and Marlon Brando refused their Oscars for the 1971 and 1973 ceremonies, respectively. If you're writing this article according to the year of the ceremony, Scott's year should be changed from 1970 to 1971; if according to the year of the work that earned them the awards, Brando's should be changed from 1973 to 1972.

The second is that there have been three Best Director nominations bestowed upon female directors; in addition to Jane Campion and Sofia Coppola, Lina Wertmüller received a Best Director nomination at the 1978 ("Annie Hall" year) Academy Awards for "Seven Beauties".

Anyway, that's what I noticed. Sorry if I troubled you; just trying to help!